- What is Interview Analysis?

- Advantages of Interviews in Research

- Disadvantages of Interviews in Research

- Ethical Considerations in Interviews

- Preparing a Research Interview

- Recruitment & Sampling for Research Interviews

- Interview Design

- How to Formulate Interview Questions

- Rapport in Interviews

- Social Desirability Bias

- Interviewer Effect

- Types of Research Interviews

- Face-to-Face Interviews

- Focus Group Interviews

- Email Interviews

- Telephone Interviews

- Stimulated Recall Interviews

- Interviews vs. Surveys

- Interviews vs Questionnaires

- Interviews and Interrogations

- How to Transcribe Interviews?

- Verbatim Transcription

- Clean Interview Transcriptions

- Manual Interview Transcription

- Automated Interview Transcription

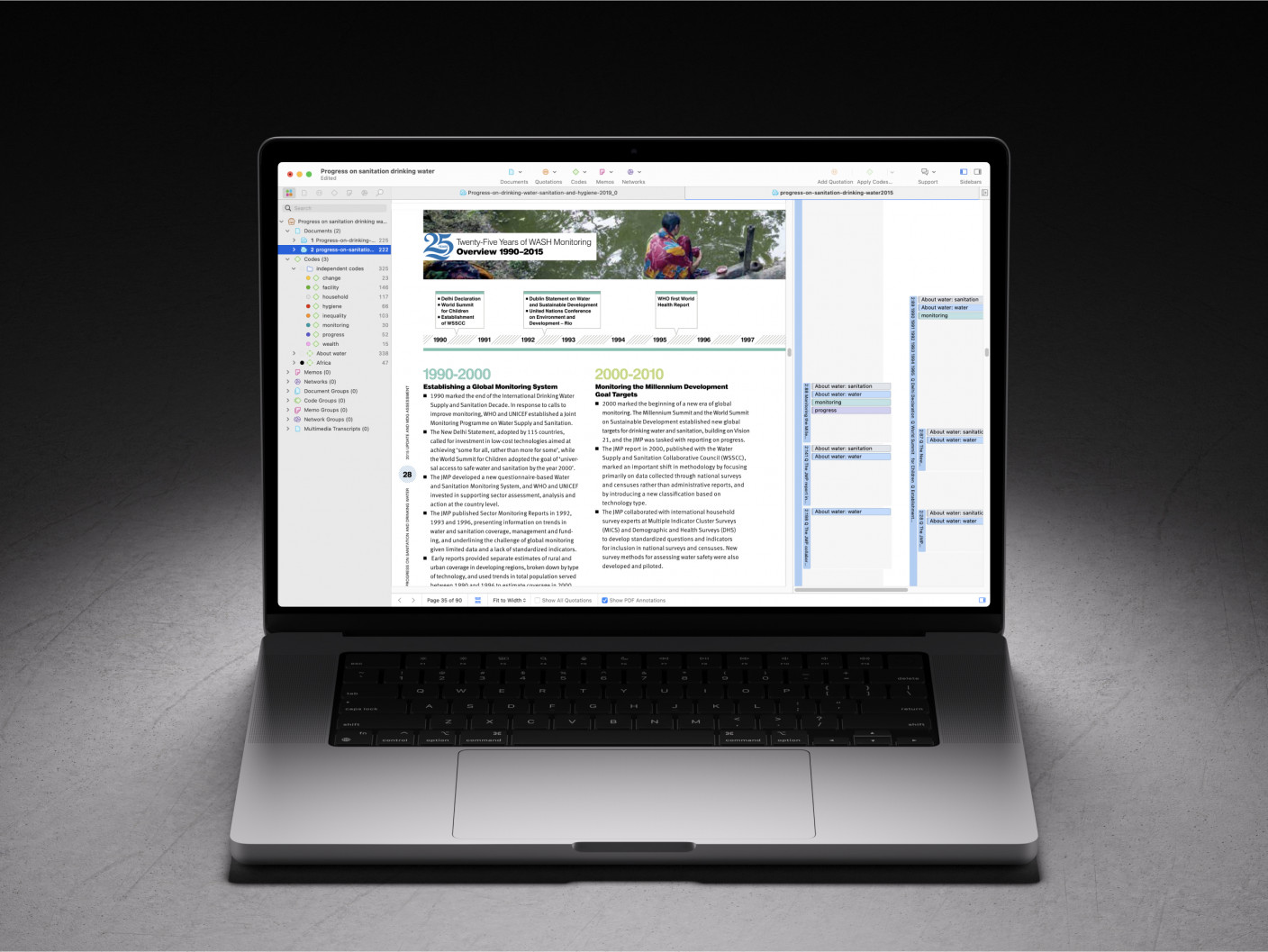

- How to Annotate Research Interviews?

- Formatting and Anonymizing Interviews

- Analyzing Interviews

- Coding Interviews

- Reporting & Presenting Interview Findings

- How to cite "The Guide to Interview Analysis"

Interviewer Effect

The interviewer effect refers to the influence that the characteristics, behavior, or presence of the interviewer can have on the responses of interview participants. It is a concept primarily studied in social sciences and qualitative research, but it can occur in any interview-based data collection. The effect can lead to incorrect or altered data, as participants may respond differently based on various factors related to the interviewer. This article delves into the essence of the interviewer effect, its effect on research quality, methods to identify it, and strategies to avoid it.

Introduction

The interviewer effect can manifest in various forms, affecting both the accuracy reporting and the quality of the collected data. Interviewer characteristics such as age, gender, ethnicity, demeanour, and level of experience can shape the dynamics of the survey interview, thereby influencing how respondents perceive and answer particular questions.

Interviewer characteristics play a pivotal role in shaping interview responses. For instance, female interviewers may elicit different responses compared to male interviewers, especially on topics like sexual behavior or race-related attitudes. Older interviewers might inadvertently introduce a self-fulfilling prophecy, where respondents adjust their answers to align with perceived expectations based on the interviewer's age. More experienced interviewers might navigate unstructured interviews more adeptly, reducing the likelihood of interviewer errors and enhancing data quality.

The interviewer effect is not confined to traditional face-to-face interviews. It extends to telephone surveys, structured interviews, unstructured interviews, and even self-administered questionnaires. In market research, for example, interviewer variance can lead to inconsistent survey statistics, undermining the validity of the findings. Similarly, in political science, interviewer effects can skew assessments of political knowledge and race relations, highlighting the need for meticulous survey methodology.

What causes the interviewer effect?

The interviewer effect arises from various factors, such as the interviewer's characteristics, behavior, and interaction style, which can affect the quality of the data collected (West & Blom, 2017).

Interviewer characteristics

Interviewer characteristics such as gender, age, race, and social status have been shown to shape the way participants respond. Participants might alter their answers to align with what they perceive as socially acceptable based on the interviewer’s demographic traits. For instance, participants tend to provide more socially desirable responses when the interviewer is of a different race, especially on sensitive topics such as race relations or politics. Studies demonstrate that respondents are more likely to adjust their answers to match what they think is expected, especially when they feel the interviewer might hold authority or opposing views. The 2017 synthesis by West and Blom identified these influences as critical in understanding interviewer-induced variability in surveys. Race-of-interviewer effects have been particularly studied in areas like political attitudes and racial issues.

Example: A study showed that people of colour (POC) tended to answer questions about racial equality differently depending on whether the interviewer was another person of colour or not, providing more favorable answers to non-POC interviewers (Campbell, 1981).

Interviewer behavior and interaction

Interviewers' verbal and nonverbal behavior can also affect responses. The way an interviewer frames a question, their tone of voice, and even their body language may subtly encourage respondents to answer in a particular way. For instance, an approving smile or a nod might prompt the respondent to expand on an answer or steer their response in the direction they believe pleases the interviewer. Research by Groves and Couper (1998) explains that interviewers using tailored responses or engaging more actively with participants can inadvertently introduce wrong information. Additionally, the extent of probing and feedback during the conversation can either help respondents clarify their thoughts or lead them toward a specific answer.

Example: Interviewers who engage in excessive probing for clarification in open-ended questions may end up influencing the depth or scope of the responses, leading to longer or more detailed answers than the participant initially intended to provide.

Presence of the interviewer

Even when interviewers try to remain neutral, their mere presence can influence how participants respond, particularly during face-to-face interactions. For sensitive topics, such as sexual behavior, substance use, or criminal activity, participants may feel self-conscious or judged, which can lead them to downplay undesirable behaviors or exaggerate socially accepted ones. Research has found that interviewer presence alone is a significant factor for socially sensitive topics (Tourangeau & Smith, 1996).

Example: A health-related study found that respondents tend to underreport behaviors like smoking or alcohol consumption when interviewed in person by someone perceived as health-conscious or authoritative, fearing judgment or social stigma.

Cultural and social expectations

Cultural norms and social hierarchies shape interactions, especially when the interviewer is perceived to be from a different background or status. In societies with strong hierarchical structures, participants may defer to the interviewer’s perceived authority, giving answers that align with the interviewer’s expected views rather than their own. This is a particularly common challenge in cross-cultural research, where participants may feel that their true opinions do not align with those of the researcher and adjust their responses accordingly. Studies like the one by Durrant et al. (2010) suggest that interviewer-participant matching by gender, race, or cultural background might reduce such effects, although it is not always feasible in large studies.

Example: In a research study in hierarchical cultures, younger participants might refrain from offering critical opinions about social or political topics when interviewed by someone older or in a position of perceived authority.

Impact of the interviewer effect on research projects

The interviewer effect can significantly compromise the quality of qualitative data, leading to measurement errors that distort the true nature of respondent characteristics and behaviors.

One of the most profound impacts of the interviewer effect is on data quality. The interviewer effect can lead to social desirability bias, where respondents provide answers they deem more acceptable rather than their true feelings or behaviors. For instance, when discussing sexual health or sexual behavior, respondents may underreport or overreport activities based on the interviewer's perceived judgment or expectations. This distortion introduces measurement errors, which can significantly affect the dependent variable and the overall integrity of the research findings.

The interviewer effect is particularly pronounced in surveys addressing sensitive topics such as sexual behavior, drug use, or race-related attitudes. Respondents may alter their answers to conform to what they believe the interviewer expects, especially when there is a significant age difference or gender disparity between them. This phenomenon can result in inconsistent data, where male and female respondents provide divergent responses not solely based on their true behaviors but influenced by the interviewer’s characteristics.

Interviewer error can further exacerbate the interviewer effect. Miscommunication, wrong questioning or inappropriate body language can lead to response effects, where the presence and behavior of the interviewer directly impact the respondent's answers. Such errors undermine the entire population representation, leading to skewed research reports and unreliable conclusions.

How to recognize the interviewer effect?

Identifying the presence of the interviewer effect is crucial for researchers aiming to enhance data collection and ensure the integrity of their findings. Several indicators and methodologies can help in recognizing this effect.

Interviewer variance can be assessed by examining the consistency of responses across different interviewers. Significant variability in survey data attributable to different interviewers suggests the presence of the interviewer effect. Statistical techniques, such as credible intervals and multilevel modeling, can quantify the extent of interviewer-induced variance in the data.

Researchers can explore correlations between interviewer characteristics (e.g., age, gender, experience) and respondent responses. For example, a consistent pattern where older interviewers are associated with lower reporting of sexual activity among younger respondents may indicate an interviewer effect. Such patterns necessitate further investigation and potential adjustment in interview designs.

Comparing results with other data sources or using grounded theory approaches can help validate the presence of the interviewer effect. Discrepancies between different data collection methods, such as telephone interviews versus face-to-face interviews, may reveal underlying interviewer-induced errors.

Minimizing the interviewer effect

The strategies to minimize the interviewer effect are critical to improving the validity of data collected through interviews. These strategies are widely supported by researchers like West and Blom (2017), Groves and Couper (1998), and others. Here's a more detailed explanation of the key strategies:

- Interviewer training: Training is essential for interviewers to maintain neutrality in their tone, phrasing, and nonverbal behavior. By teaching them how to avoid leading questions, reduce judgmental reactions, and adhere to a structured approach, researchers can limit the variability introduced by individual interviewers. This training ensures interviewers remain consistent in their interactions with participants.

- Standardized interview protocols: Using structured or semi-structured interview guides helps ensure that all interviewers ask the same questions in the same way. This prevents personal interpretation of questions or tone, minimizing errros. Standardized protocols are particularly useful in large-scale studies to maintain consistency across interviews.

- Matching interviewers to participants: In some cases, pairing interviewers with participants based on shared demographic characteristics (such as gender or race) can make participants feel more at ease. While this strategy helps reduce discomfort in sensitive topics, it must be implemented carefully to avoid introducing the wrong information, like assumptions about shared views.

- Minimizing nonverbal cues: Interviewers are trained to limit nonverbal communication such as facial expressions, gestures, or body language that may unintentionally influence participants. Neutrality in these cues helps ensure participants do not feel guided or judged, particularly in face-to-face interviews where nonverbal communication can be significant.

- Using technology: Tools like computer-assisted interviewing (CAI) help standardize the way questions are asked. These systems ensure that interviewers follow a script precisely, reducing the potential for interviewer-induced effects by removing personal interpretation and ensuring consistency in how questions are posed.

- Blinding interviewers to study hypotheses: Keeping interviewers unaware of the specific research objectives helps prevent them from consciously or unconsciously steering participants toward certain responses. This blinding strategy helps maintain the objectivity of the data collection process.

Conclusion

The interviewer effect presents a significant challenge in qualitative and interview-based research, as it has the potential to introduce inaccurate information and alter the authenticity of the data collected. Recognizing that the characteristics, behavior, and even the mere presence of the interviewer can influence participants' responses is critical to improving data quality. By understanding the causes and manifestations of the interviewer effect, researchers can adopt strategies that minimize its impact, ensuring more reliable and valid findings.

Effective interviewer training, the use of standardized protocols, and careful matching of interviewers to participants are essential in mitigating the influence of the interviewer effect. Additionally, employing technology like computer-assisted interviewing (CAI) and maintaining interviewer neutrality can further reduce the potential for error. By addressing these factors proactively, researchers can enhance the integrity of their research projects, allowing the true voices of participants to emerge and leading to more accurate representations of the social phenomena under study. In doing so, the researcher not only improves the quality of the data but also ensures that the conclusions drawn are both meaningful and trustworthy, ultimately contributing to the advancement of knowledge in social sciences.

References

- West, B. T., & Blom, A. G. (2017). Explaining interviewer effects: A research synthesis. Journal of Survey Statistics and Methodology, 5(2), 175–211.

- Campbell, A. L. (1981). The sense of well-being in America: Recent patterns and trends. McGraw-Hill.

- Groves, R. M., & Couper, M. P. (1998). Nonresponse in household interview surveys. Wiley.

- Tourangeau, R., & Smith, T. W. (1996). Asking sensitive questions: The impact of data collection mode, question format, and question context. Public Opinion Quarterly, 60(2), 275–304.

- Durrant, G. B., Groves, R. M., Staetsky, L., & Steele, F. (2010). Effects of interviewer attitudes and behaviors on refusal in household surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly, 74(1), 1–36.