- What is Interview Analysis?

- Advantages of Interviews in Research

- Disadvantages of Interviews in Research

- Ethical Considerations in Interviews

- Preparing a Research Interview

- Recruitment & Sampling for Research Interviews

- Interview Design

- How to Formulate Interview Questions

- Rapport in Interviews

- Social Desirability Bias

- Interviewer Effect

- Types of Research Interviews

- Face-to-Face Interviews

- Focus Group Interviews

- Email Interviews

- Telephone Interviews

- Stimulated Recall Interviews

- Interviews vs. Surveys

- Interviews vs Questionnaires

- Interviews and Interrogations

- How to Transcribe Interviews?

- Verbatim Transcription

- Clean Interview Transcriptions

- Manual Interview Transcription

- Automated Interview Transcription

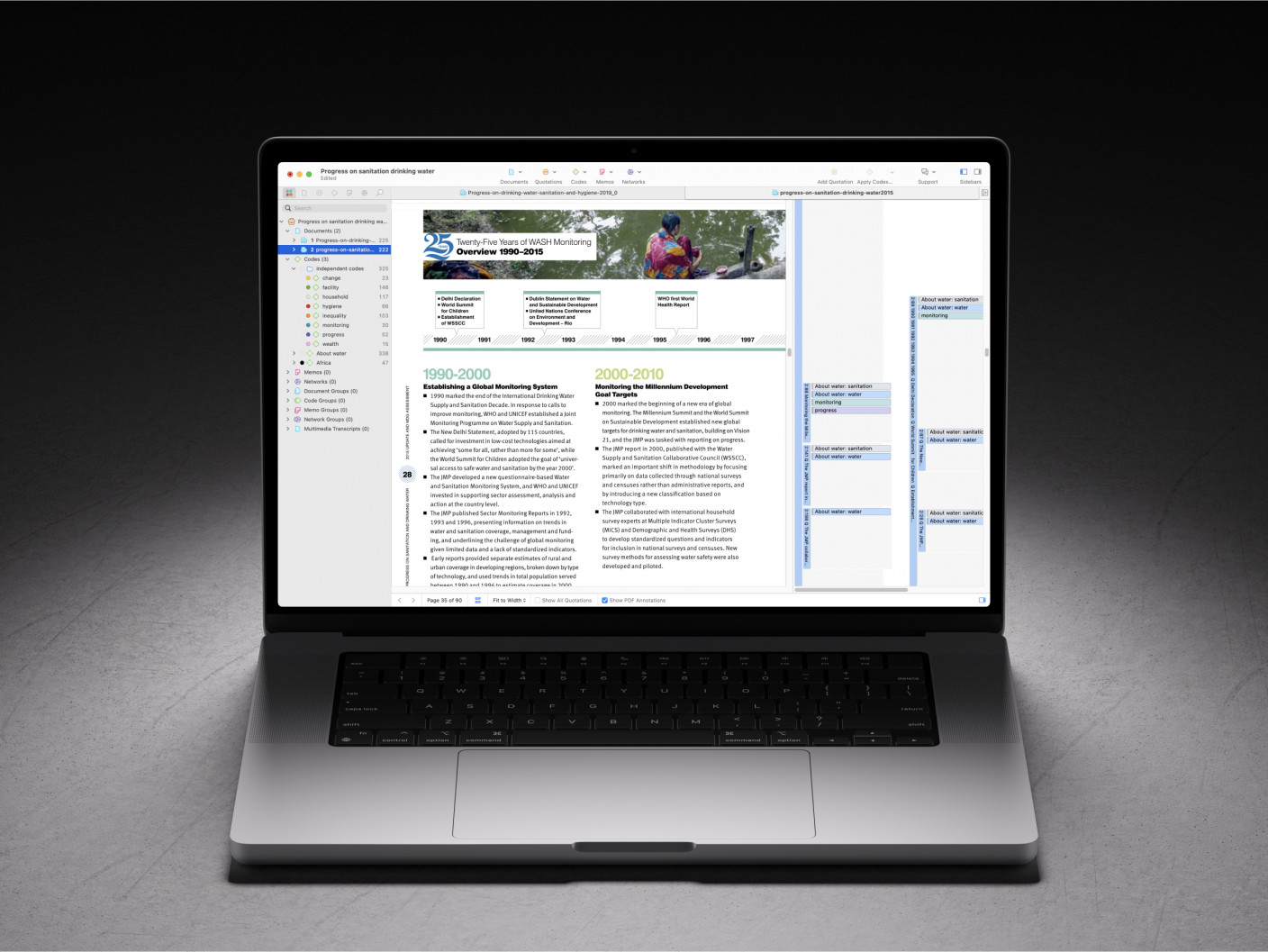

- How to Annotate Research Interviews?

- Formatting and Anonymizing Interviews

- Analyzing Interviews

- Coding Interviews

- Reporting & Presenting Interview Findings

- How to cite "The Guide to Interview Analysis"

Disadvantages of Interviews in Research

Interviews are a staple method for data collection in qualitative research, and they are celebrated for capturing rich, nuanced insights. But beneath the surface lie potentially critical hidden flaws that could skew the information. This article delves into the key disadvantages associated with the interview process in qualitative research, particularly when conducting interviews in person, whether through structured interviews, unstructured interviews, or other interview formats.

Introduction

It is unarguable that interviews convey the densest and deepest information when it comes to data collection. While other data collection methods, such as surveys or focus groups, provide valuable insights and a wider net of information, they do not provide the deeper understanding that interviews do.

Nevertheless, no method is perfect and some disadvantages can permeate and lower the quality of collected information. This can go from poor questioning like asking questions that will not give any insight into the research project or psychological effects where the interviewer unconsciously manipulates the participant's responses.

Interviews are a widely used qualitative research method, offering a deeper understanding of participants’ experiences and providing valuable insights that other data collection methods, such as surveys or quantitative methods, might not capture. However, while interviews provide a wealth of qualitative data, they also come with a set of disadvantages that qualitative researchers must navigate carefully.

Interview disadvantages compared to other data collection methods

Time-consuming

One of the most significant disadvantages of interviews is that they are time-consuming. The interview process involves several stages, each demanding substantial time. Qualitative researchers must plan and design the interviews meticulously, ensuring that the interview questions are well-crafted to elicit meaningful responses. Conducting qualitative research often requires scheduling in-person or online interviews, which can be logistically challenging, especially when participants are spread across different locations or have limited availability.

During the interview itself, whether it’s a one-on-one interview, a panel interview, or even a phone interview, the process requires careful attention to detail. Researchers must take the time to build rapport, ask follow-up questions, and seek clarification to fully understand participants' responses. After the interview, the transcription and data analysis stages are equally time-intensive. This resource-intensive nature of interviews can limit the number of interviews a research team can conduct, potentially affecting the breadth of data collected and the overall scope of the research project.

Limited anonymity

Interviews, especially face-to-face interviews, often require participants to share personal experiences and opinions in a setting where anonymity is limited. Unlike other data collection methods, such as surveys or online questionnaires, interviews do not provide the same level of anonymity, which can affect participants' willingness to share openly. This is particularly true in research projects that involve sensitive topics or require participants to disclose personal or potentially stigmatizing information.

The lack of anonymity can lead to social desirability bias, where participants modify their responses to align with what they perceive as socially acceptable or to avoid judgment. This limitation can result in data that is less reflective of participants' true thoughts and feelings, thus affecting the quality of the qualitative data collected. Qualitative researchers must emphasize informed consent and confidentiality to encourage honest and open responses, though this does not eliminate the impact of limited anonymity.

Resource-intensive

Conducting interviews requires significant resources, including time, money, and skilled personnel. This resource-intensive nature is a major disadvantage, particularly for smaller research teams or projects with limited budgets. In-person interviews, for example, may require travel expenses, venue bookings, and equipment for recording, all of which add to the overall cost of the research. Even online interviews, while potentially less costly, require reliable technology and internet access, as well as the time and effort needed to schedule and conduct the interviews.

The resource demands extend beyond the interview itself to the data analysis phase. Transcribing interviews is a time-consuming and labour-intensive process, often requiring additional resources such as transcription software or professional transcribers. Moreover, interview analysis, particularly in complex research projects, requires sophisticated software and trained analysts, further adding to the costs.

Potential for inaccurate recall

Interviews often rely on participants’ ability to recall past experiences, opinions, or events. However, human memory is fallible, and participants may provide inaccurate or incomplete accounts during the interview process. Participants may unintentionally omit details, reconstruct events differently based on current understandings, or even blend multiple experiences into a single narrative.

In some research contexts, this issue is particularly problematic, such as in retrospective studies where accurate recall is crucial for understanding the phenomena under investigation. Qualitative researchers can mitigate this risk by using techniques such as triangulation, where information from interviews is cross-checked with other data sources, or by employing memory aids, such as timelines, to help participants recall events more accurately. In qualitative research, interviews create data in the moment, reflecting the participant's current perspective and voice. However, these can change over time.

Cultural and language barriers

In cross-cultural research, interviews can present challenges related to language differences and cultural nuances. These barriers can lead to misunderstandings, misinterpretations, or even offences, which can compromise the quality of the data collected. For instance, certain questions or topics might be perceived differently in various cultural contexts, leading to responses that are influenced by cultural norms rather than the participant’s thoughts or experiences.

Language barriers are particularly challenging in qualitative research, where the richness of the data often depends on nuanced expression and detailed description. When participants are not fluent in the language of the interview, or when translations are required, there is a risk that the original meaning of responses will be lost or altered. Qualitative researchers must be sensitive to these issues and consider involving bilingual interviewers or cultural mediators to ensure that the data collected is as accurate and representative as possible.

Ethical considerations and informed consent

Conducting interviews, particularly on sensitive topics, raises important ethical considerations. Researchers must obtain informed consent from participants, ensuring that they fully understand the purpose of the research, how their data will be used, and their right to withdraw from the study at any time. However, the process of obtaining informed consent can be complex, particularly in cases where power dynamics are at play, such as in interviews with vulnerable populations or in hierarchical organizations.

Moreover, the personal interaction inherent in interviews can raise ethical concerns around privacy and confidentiality. Participants may share sensitive information during an interview that they later regret or that could have negative consequences if disclosed. Qualitative researchers must navigate these ethical challenges carefully, balancing the need to collect valuable insights with the responsibility to protect participants’ rights and well-being.

Disadvantages of different types of interviews

When analyzing the disadvantages of interviews in different formats like focus groups, telephone interviews, emails, and face-to-face settings, it's essential to consider both logistical and methodological challenges.

Focus groups

In focus groups, one major disadvantage is the potential for dominant participants to skew the conversation. Some individuals naturally speak more than others, and their opinions may overshadow quieter members. This dominance can distort the group’s dynamics and suppress diverse perspectives. Additionally, focus groups are prone to groupthink, where participants feel pressure to conform to the majority opinion rather than express their true thoughts. This social conformity can limit the authenticity of the data collected.

The success of focus groups heavily depends on the moderator’s ability to balance the conversation and engage all participants equally, which can be challenging. Poor moderation may lead to some participants feeling excluded or less willing to contribute. Another drawback is the logistical difficulty of scheduling sessions that work for multiple people. Finding a common time for everyone can delay the process and reduce participation. Finally, focus groups often limit the depth of responses because participants must share time, preventing a more comprehensive exploration of individual perspectives.

Face-to-face interviews

Face-to-face interviews provide the richest data in terms of depth and personal connection, but they are not without drawbacks. One significant disadvantage is the time-consuming nature of these interviews. Coordinating schedules, arranging locations, and conducting in-person meetings can take up a considerable amount of time, both for the researcher and the participants. This process can be especially challenging if travel is involved. Another limitation is the potential for social desirability bias. When participants are sitting directly in front of an interviewer, they may feel pressure to give socially acceptable responses rather than expressing their true thoughts. This can skew the data and reduce its authenticity. Face-to-face interviews also tend to be more expensive.

The costs associated with travel, venue rental, and participant compensation can add up, making this method less feasible for larger-scale studies. Additionally, interviewer bias can inadvertently influence the participant’s responses. Non-verbal cues, facial expressions, or even the tone of voice from the interviewer can shape how the participant answers, potentially impacting the data. Finally, logistical challenges, such as finding a comfortable, neutral, and private space for sensitive interviews, can affect the quality of the responses, especially if participants feel uncomfortable or rushed.

Telephone interviews

Telephone interviews, while convenient, present several unique challenges. One of the biggest limitations is the absence of visual cues. Without body language or facial expressions, it becomes more difficult for interviewers to gauge emotions, discomfort, or hesitations, which can provide valuable context. The lack of visual connection also makes it harder to establish rapport with participants, potentially leading to shorter, less engaging conversations. This medium can feel impersonal, and distractions in the participant’s environment can further reduce their focus and engagement. Technical issues, such as poor call quality or dropped connections, can interrupt the flow of the interview and lead to incomplete or misunderstood responses. Telephone interviews are often shorter than face-to-face ones, as participants tend to give briefer responses without the same level of engagement. This can limit the richness of the data collected. Participants may hesitate to discuss sensitive topics over the phone, leading to less candid responses.

Psychological effects in interviews

During interviews, several psychological effects can emerge that could influence both the interviewer's and the participant's behaviour and responses. Here are some key psychological effects to consider and reflect on:

Social desirability bias

Social desirability bias occurs when participants adjust their responses to align with what they believe is socially acceptable or favourable in the eyes of the interviewer. This is particularly common in interviews where sensitive or controversial topics are discussed. Participants might downplay behaviours or opinions they perceive as undesirable and emphasize those they believe are more acceptable. This can lead to inaccurate or skewed data, as the true feelings or behaviours of the participant are not fully revealed.

The Hawthorne effect

A peculiar disadvantage of interviews is what's known as the "Hawthorne effect." This is similar to the social desirability bias as it occurs when participants alter their behaviour simply because they know they're being observed or interviewed. Named after a series of studies in the 1920s at the Hawthorne Works factory (Levitt & List, 2011), this effect can lead participants to give answers they think the interviewer wants to hear or to behave differently during the interview than they would in their everyday lives. Essentially, the very act of being interviewed can change how people respond, making it tricky to get entirely authentic data.

The Hawthorne effect is named after a series of studies conducted at Chicago's Western Electric Hawthorne Works factory in the 1920s-1930s. Researchers were investigating how different working conditions, like lighting levels, affected worker productivity. They found that productivity improved whenever any change was made, even when the conditions were actually worsened, simply because the workers knew they were being observed. This effect showed that the mere presence of researchers and attention to workers' activities could influence behaviour, leading to increased productivity regardless of the specific changes made.

The telephone effect

The "telephone effect" occurs when the lack of visual context can lead to misunderstandings, misinterpretations, or a loss of subtle emotional cues. Unlike face-to-face interviews, where body language, facial expressions, and other non-verbal cues play a significant role in communication, phone or virtual interviews rely heavily on voice alone. As a result, the richness of the data might be compromised, making it harder for the interviewer to fully grasp the participant's emotions or intentions.

One famous example of the "telephone effect" impacting data collection is the Hite Report on female sexuality, conducted by Shere Hite in the 1970s. While the report was groundbreaking in its findings, Hite collected much of her data through written questionnaires rather than face-to-face interviews (Shere, 1976). This reliance on non-personal communication methods, similar to the "telephone effect," may have led to some misinterpretations or a lack of depth in responses, as participants could not clarify their thoughts or emotions in real-time with an interviewer. Critics argued that the lack of direct interaction might have affected the authenticity and richness of the data.

Recall bias

Recall bias happens when participants have difficulty remembering past events, leading to incomplete or altered recollections. This bias can be particularly problematic in interviews, as the quality of qualitative data often relies on participants’ ability to provide detailed accounts of their experiences. Participants may unintentionally omit details, blend multiple events, or reconstruct memories based on their beliefs or emotions. This can lead to data that is not fully reliable or representative.

Paradox of self-disclosure

The "paradox of self-disclosure." During interviews, participants might start guarded but gradually become more open as they build rapport with the interviewer. Interestingly, this can sometimes lead to them sharing more personal or sensitive information than originally intended. However, after the interview, participants might experience "disclosure regret," where they feel uncomfortable or worried about having shared too much. This phenomenon can impact participants' feelings toward their involvement in the study and affect their responses if follow-up interviews are conducted.

The paradox of self-disclosure was evident in Philip Zimbardo's Stanford Prison Experiment (Zimbardo, 1973), where participants gradually disclosed more about themselves and adopted behaviours they might not have anticipated. As the simulated prison environment intensified, some participants (playing the role of guards) began to exhibit increasingly aggressive behaviour, while others (playing the role of prisoners) became more submissive. Many of the participants later expressed regret or discomfort with how deeply they had engaged in their roles and the personal aspects of themselves they revealed during the experiment, highlighting the paradox where initial openness led to uncomfortable self-disclosure as the study progressed.

Conclusion

Interviews are a powerful qualitative research method that can provide deep insights into human experiences and behaviours but come with disadvantages. The interview process is time-consuming and resource-intensive. Additionally, the lack of anonymity and the challenges of cross-cultural and language barriers further complicate the use of interviews in qualitative research.

Despite these challenges, interviews remain a valuable tool in the qualitative researcher's arsenal, particularly when the research question demands a deeper understanding of complex phenomena. However, qualitative researchers must be mindful of the disadvantages of interviews and take steps to mitigate these challenges wherever possible, ensuring that the data collected is both of high quality and ethically sound. By carefully considering these factors, research teams can conduct interviews that provide valuable insights while minimizing the associated risks and limitations.

References

- Hite, Shere. (1976). The Hite report : a nationwide study on female sexuality. New York :Macmillan,

- Levitt, S. D., & List, J. A. (2011). Was there really a Hawthorne effect at the Hawthorne plant? An analysis of the original illumination experiments. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 3(1), 224–238. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.3.1.224

- Zimbardo, P. G. (1973). On the ethics of intervention in human psychological research: With special reference to the Stanford prison experiment. Cognition, 2(2), 243-256.