- What is Interview Analysis?

- Advantages of Interviews in Research

- Disadvantages of Interviews in Research

- Ethical Considerations in Interviews

- Preparing a Research Interview

- Recruitment & Sampling for Research Interviews

- Interview Design

- How to Formulate Interview Questions

- Rapport in Interviews

- Social Desirability Bias

- Interviewer Effect

- Types of Research Interviews

- Face-to-Face Interviews

- Focus Group Interviews

- Email Interviews

- Telephone Interviews

- Stimulated Recall Interviews

- Interviews vs. Surveys

- Interviews vs Questionnaires

- Interviews and Interrogations

- How to Transcribe Interviews?

- Verbatim Transcription

- Clean Interview Transcriptions

- Manual Interview Transcription

- Automated Interview Transcription

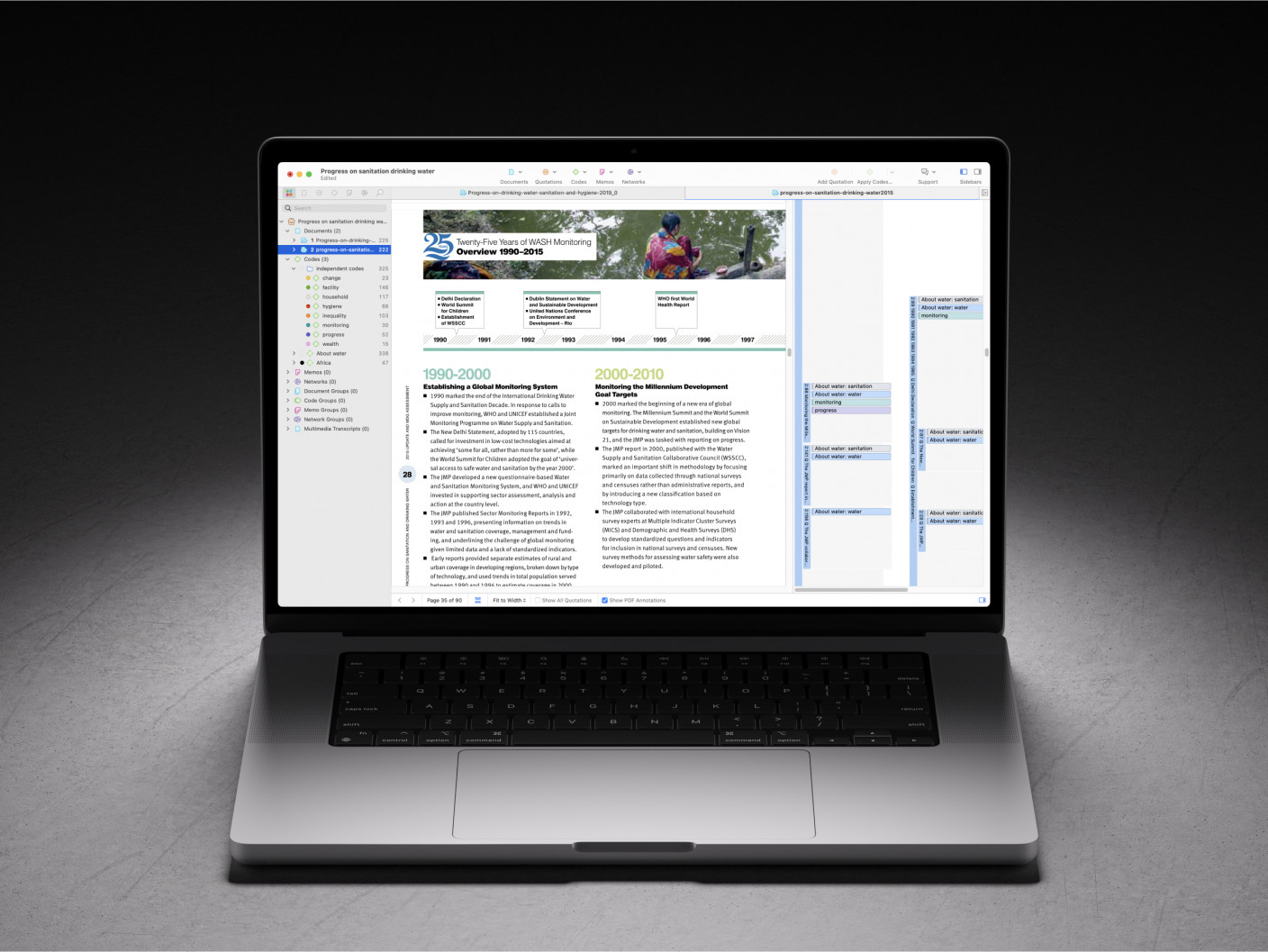

- How to Annotate Research Interviews?

- Formatting and Anonymizing Interviews

- Analyzing Interviews

- Coding Interviews

- Reporting & Presenting Interview Findings

- How to cite "The Guide to Interview Analysis"

Ethical considerations in interviews

Ethical considerations for interviews are fundamental to ensuring that the interview process respects the dignity, rights, and well-being of participants. Whether you are conducting a research interview or a job interview, adhering to ethical standards is essential for maintaining integrity and fairness. In this article, we will go over how to conduct interviews ethically, including the ethical recruitment process, consent and confidentiality, as well as gaining IRB and ethical approval.

Introduction

In interviews, ethical conduct safeguards promote transparency and build trust between the interviewer and the interviewee. This is especially important when dealing with sensitive information or a vulnerable population.

First and foremost, obtaining informed consent is essential. This involves providing participants with clear and thorough information about the study’s purpose, the interview process, the types of questions that will be asked, and any potential risks or benefits. Participants must agree to participate voluntarily, fully aware that they can withdraw from the interview or the research at any point without facing any negative consequences.

Confidentiality is another key ethical issue. Researchers are responsible for protecting the identities of their participants and ensuring that personal information is not disclosed. This often means anonymizing data or using pseudonyms in reports. Researchers must also securely store collected data and limit access to only those directly involved in the study. Handling sensitive data requires careful consideration, especially when participants share private or emotionally charged information.

Respect for autonomy is equally critical. Researchers must ensure that participants are not coerced into participation and feel comfortable throughout the interview process. Any signs of discomfort or reluctance should be met with an opportunity to pause or withdraw, and interviewers should avoid pressuring participants into answering any questions they feel uneasy about. Similarly, researchers should refrain from asking leading questions or using manipulative techniques that could sway responses, as these actions compromise the integrity of the data.

Another important ethical aspect is ensuring that participants are not harmed, either emotionally or psychologically, during or after the interview. Researchers must be sensitive to the potential impact of discussing certain topics, especially those that may trigger stress or trauma. If a topic is likely to cause distress, participants should be given advance notice, and the interviewer should be prepared to offer support or resources if needed.

Finally, researchers are often required to submit their research design to an ethics committee or institutional review board for approval before conducting interviews. This oversight helps ensure that the study meets ethical standards and that participants are protected throughout the research process. By adhering to these ethical principles, researchers can build trust with participants and uphold the integrity of their research findings.

How to conduct interviews ethically

Ethical interviewing practices ensure that the dignity and rights of participants are respected throughout the interview process. Whether the goal is to gather research data or recruit the best candidate for a job role, the principles of fairness, respect, and confidentiality are key to ethical conduct. Conducting interviews ethically starts with understanding and implementing ethical considerations at every step of the interview process.

Ethical recruitment process

In qualitative research, the recruitment of participants must be handled with great care and consideration to ensure ethical standards are upheld. The recruitment process not only sets the tone for the relationship between the researcher and participants but also serves as a foundation for the integrity of the research. Ethical recruitment involves transparency, respect, and protection of participants' rights throughout the entire process.

Respecting participants' autonomy is essential in the recruitment process. Researchers must ensure that participants make independent decisions about their involvement. This means avoiding any pressure or persuasion to participate, particularly for vulnerable populations who might feel obliged to join due to a power imbalance, such as students, patients, or employees.

Ethical recruitment requires a fair selection of participants, meaning that the inclusion and exclusion criteria must be carefully considered and justified. Researchers should ensure that participant selection is equitable, avoiding exploitation or discrimination. Vulnerable populations, such as children, individuals with disabilities, or economically disadvantaged individuals, should only be included when necessary, and their participation must be handled with extra care.

Researchers should avoid relying exclusively on convenience sampling, as it may disproportionately burden certain groups or exclude those whose perspectives are vital to understanding the research topic. Inclusivity and diversity in recruitment help ensure research findings are valid and representative of the broader population.

During recruitment, researchers must maintain a high level of transparency about the study’s purpose, funding sources, and how findings will be disseminated. Participants should be made aware of who is conducting the research, who is sponsoring it, and any potential conflicts of interest. This openness fosters trust and allows participants to make informed choices about their involvement.

Additionally, researchers should communicate the potential benefits and limitations of the research. If the study is designed to have a social or public impact, participants should be informed about how their contributions may influence future policies or practices.

Consent and confidentiality

One of the most fundamental aspects of ethical interviewing is obtaining informed consent. Informed consent ensures that participants understand the purpose of the interview, the potential risks involved, and their right to voluntary participation. It is essential to explain to the participants how their data will be used, ensuring they are aware of their ability to withdraw from the process at any time without negative consequences. This transparency helps build trust between the interviewer and the participant, a necessary foundation for any ethical interview. Consent forms should be detailed but easy to understand: Avoid jargon or overly technical terms when explaining the nature of the interview, the potential risks and benefits, and the confidentiality protocols in place.

Maintaining confidentiality is another key aspect of ethical interviewing. Protecting participants’ personal information is crucial in both research and recruitment. For research interviews, this means anonymizing data and securely storing any recordings or transcripts to prevent unauthorized access. Ethical practices dictate that only authorized personnel should have access to the data, and participants should be informed about how their information will be used. In the recruitment process, confidentiality is just as important. Participants trust that the information they share during the interview will not be disclosed to unauthorized individuals or misused in any way.

Avoiding leading questions is crucial for ethical interviewing. Leading questions can unfairly influence the responses of the participants, potentially skewing the results. Instead, open-ended questions should be used to allow participants or candidates to provide their genuine answers. Ethical interviews must be free from manipulation and aim to gather authentic information based on the participant’s or candidate’s responses.

Respect for the participants is at the heart of ethical interviewing practices. This respect manifests in several ways, such as valuing their time, providing context for each question, and ensuring they feel comfortable throughout the process. In research interviews, this includes creating a safe and supportive environment where participants can express themselves without fear of judgment or repercussions.

Sensitive topics and cultural sensitivity

Another ethical consideration in interviews is handling sensitive topics with care. Interviews, especially in research contexts, often deal with sensitive subjects such as personal experiences, trauma, or controversial topics. Researchers must approach these interviews with empathy and understanding, allowing participants to skip questions or withdraw from the interview if they feel uncomfortable. Providing context before delving into sensitive areas is essential to prepare participants for what lies ahead. For example, informing participants that certain questions may touch on sensitive topics gives them the option to choose whether to continue. This approach respects the participant’s autonomy and ensures that the interview process does not cause unnecessary harm.

When recruiting participants from diverse cultural backgrounds, researchers must demonstrate cultural sensitivity. This means understanding and respecting cultural norms, values, and practices that may influence a person’s willingness or comfort in participating. Recruitment strategies should be adapted to reflect cultural considerations, using appropriate language and channels that are accessible and respectful of participants’ identities and backgrounds.

Unethical interview practices can significantly harm participants and undermine research quality. Real-world cases of unethical interview practices underscore the critical importance of conducting research in an ethical manner and obtaining approval from the local ethics committee or institutional review board.

For example, the Tearoom Trade Study (1970) was a study in which the researcher interviewed men about their sexual behaviour without informing them that they were being studied. Interviews were conducted under false pretenses, and participants were not given the opportunity to consent. This blatant disregard for privacy and autonomy violated ethical principles, as the participants were unaware that personal and sensitive information was being collected and used for research.

Upholding principles such as informed consent, respect for emotional boundaries, and protecting privacy are essential to preserving the integrity of the research and protecting participants from harm.

Gaining IRB and ethical approval

An Institutional Review Board (IRB) is a committee established to review, approve, and monitor research involving human participants. The primary purpose of an IRB is to ensure that the rights, welfare, and safety of participants are protected throughout the research process.

The process of gaining IRB approval begins with submitting a detailed research proposal outlining the study's objectives, methods, and ethical considerations. The IRB reviews the proposal to ensure that the research does not pose undue risk to participants and that ethical guidelines are followed. One of the key ethical considerations in this process is obtaining informed consent. The IRB will assess how researchers plan to obtain consent from participants and ensure that participants understand their rights, including the right to withdraw from the study at any time.

Another important aspect of gaining IRB approval is demonstrating how the researchers will maintain confidentiality. The IRB requires researchers to outline how they will store and handle sensitive data, ensuring that participants' personal information is protected. Ethical practices related to confidentiality include anonymizing data, securely storing recordings or transcripts, and ensuring that only authorized individuals have access to the information.

In addition to protecting participants' privacy, the IRB also evaluates the potential risks and benefits of the research. Researchers must demonstrate that the benefits of the study outweigh any potential risks to the participants and that appropriate measures are in place to minimize harm. For example, in studies dealing with sensitive topics, researchers may be required to provide support resources, such as counselling or helplines, to participants who may experience emotional distress during the interview process.

Gaining IRB or ethical approval is a critical step in conducting research interviews ethically, and journal editors often require proof of IRB approval to accept a study for publication. The IRB ensures that the research is designed in a way that protects participants' rights and well-being, from obtaining informed consent to maintaining confidentiality and minimizing potential risks. Without IRB approval, researchers cannot proceed with their study, underscoring the importance of adhering to ethical standards throughout the interview process.

IRB's worldwide

Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) or their equivalents vary depending on the country, though the core principles of protecting human participants in research remain largely consistent. Different countries have their own regulatory frameworks and ethical guidelines for research involving human subjects, and these bodies may be referred to by different names.

Examples of IRB-equivalent bodies in different countries

United States: The IRB system is governed by federal regulations, primarily under the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The guiding principles come from the Belmont Report, which outlines respect for persons, beneficence, and justice.

United Kingdom: The equivalent to the IRB is the Research Ethics Committee (REC). In the UK, these committees are governed by the Health Research Authority (HRA) and operate under ethical guidelines set by the National Health Service (NHS).

European Union: In the EU, research ethics are typically overseen by Ethics Committees (ECs). These committees operate under the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), ensuring the ethical conduct of research involving human subjects, especially when it comes to privacy and data protection.

Canada: Research Ethics Boards (REBs) are the equivalent of IRBs in Canada. They follow the Tri-Council Policy Statement (TCPS 2), which is a set of guidelines for the ethical conduct of research involving humans.

Australia: In Australia, the equivalent body is the Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC). The HRECs operate under the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) guidelines.

Japan: Japan has Ethics Committees that operate under guidelines provided by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW). These committees are responsible for ensuring the ethical treatment of human subjects in research.

India: The Institutional Ethics Committees (IECs) are similar to IRBs and are governed by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) and regulations from the Drugs Controller General of India (DCGI).

Across most countries, ethical review processes are guided by a shared set of international principles designed to protect participants in research. These principles include the importance of informed consent, ensuring that participants fully understand the nature of the study and their involvement before agreeing to take part. Another key principle is risk minimization, where researchers are obligated to reduce potential harm to participants as much as possible. Confidentiality and privacy are also fundamental, ensuring that personal information is safeguarded and that participants' identities remain protected. Lastly, fair participant selection is emphasized to prevent the exploitation or exclusion of vulnerable populations, ensuring equity in how research participants are chosen.

Conclusion

Ethical considerations for interviews are essential to ensuring fairness, transparency, and respect for participants and job candidates. Ethical interviewing practices, from obtaining informed consent to maintaining confidentiality, are fundamental to protecting the dignity and rights of all individuals involved in the interview process. For researchers, gaining IRB approval is necessary to ensure that ethical standards are upheld throughout the study. By adhering to ethical guidelines, interviewers can build trust, promote transparency, and make decisions that align with ethical practices and acceptable behaviour, benefiting both the researcher and the individuals involved.

References

- Humphreys, Laud. Tearoom Trade: Impersonal Sex in Public Places. Aldine Publishing, 1970.