What Is a Research Design? | Definition, Types & Guide

- Introduction

- Parts of a research design

- Types of research methodology in qualitative research

- Narrative research designs

- Phenomenological research designs

- Grounded theory research designs

- Ethnographic research designs

- Case study research design

- Important reminders when designing a research study

Introduction

A research design in qualitative research is a critical framework that guides the methodological approach to studying complex social phenomena. Qualitative research designs determine how data is collected, analyzed, and interpreted, ensuring that the research captures participants' nuanced and subjective perspectives. Research designs also recognize ethical considerations and involve informed consent, ensuring confidentiality, and handling sensitive topics with the utmost respect and care. These considerations are important in qualitative research and other contexts where participants may share personal or sensitive information. A research design should convey coherence as it is essential for producing high-quality qualitative research, often following a recursive and evolving process.

Parts of a research design

Theoretical concepts and research question

The first step in creating a research design is identifying the main theoretical concepts. To identify these concepts, a researcher should ask which theoretical keywords are implicit in the investigation. The next step is to develop a research question using these theoretical concepts. This can be done by identifying the relationship of interest among the concepts that catch the focus of the investigation. The question should address aspects of the topic that need more knowledge, shed light on new information, and specify which aspects should be prioritized before others. This step is essential in identifying which participants to include or which data collection methods to use. Research questions also put into practice the conceptual framework and make the initial theoretical concepts more explicit. Once the research question has been established, the main objectives of the research can be specified. For example, these objectives may involve identifying shared experiences around a phenomenon or evaluating perceptions of a new treatment.

Methodology

After identifying the theoretical concepts, research question, and objectives, the next step is to determine the methodology that will be implemented. This is the lifeline of a research design and should be coherent with the objectives and questions of the study. The methodology will determine how data is collected, analyzed, and presented. Popular qualitative research methodologies include case studies, ethnography, grounded theory, phenomenology, and narrative research. Each methodology is tailored to specific research questions and facilitates the collection of rich, detailed data. For example, a narrative approach may focus on only one individual and their story, while phenomenology seeks to understand participants' lived common experiences. Qualitative research designs differ significantly from quantitative research, which often involves experimental research, correlational designs, or variance analysis to test hypotheses about relationships between two variables, a dependent variable and an independent variable while controlling for confounding variables.

Literature review

After the methodology is identified, conducting a thorough literature review is integral to the research design. This review identifies gaps in knowledge, positioning the new study within the larger academic dialogue and underlining its contribution and relevance. Meta-analysis, a form of secondary research, can be particularly useful in synthesizing findings from multiple studies to provide a clear picture of the research landscape.

Data collection

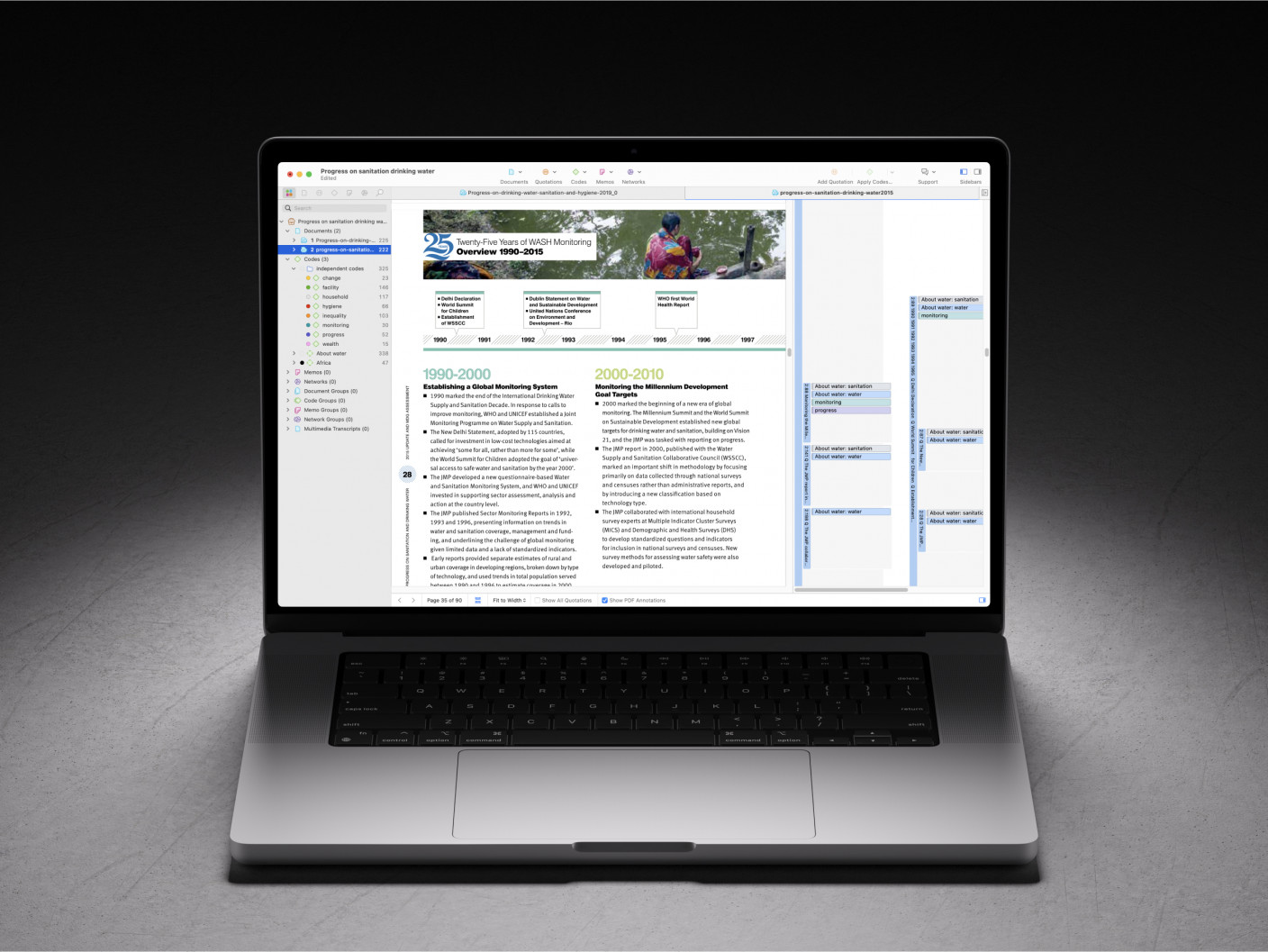

The sampling method in qualitative research is designed to look deeply into specific phenomena rather than to generalize findings across a broader population. The data collection methods—whether interviews, focus groups, observations, or document analysis—should align with the chosen methodology, ethical considerations, and other factors such as sample size. In some cases, repeated measures may be collected to observe changes over time.

Data analysis

Analysis in qualitative research typically involves methods such as coding and thematic analysis to distill patterns from the collected data. This process delineates how the research results will be systematically derived from the data. It is recommended that the researcher ensures that the final interpretations are coherent with the observations and analyses, making clear connections between the data and the conclusions drawn. Reporting should be narrative-rich, offering a comprehensive view of the context and findings.

Overall, a coherent qualitative research design that incorporates these elements facilitates a study that not only adds theoretical and practical value to the field but also adheres to high quality. This methodological thoroughness is essential for achieving significant, insightful findings. Examples of well-executed research designs can be valuable references for other researchers conducting qualitative or quantitative investigations. An effective research design is critical for producing robust and impactful research outcomes.

Types of research methodology in qualitative research

Each qualitative research design is unique, diverse, and meticulously tailored to answer specific research questions, meet distinct objectives, and explore the unique nature of the phenomenon under investigation. The methodology is the wider framework that a research design follows. Each methodology in a research design consists of methods, tools, or techniques that compile data and analyze it following a specific approach.

The methods enable researchers to collect data effectively across individuals, different groups, or observations, ensuring they are aligned with the research design. The following list includes the most commonly used methodologies employed in qualitative research designs, highlighting how they serve different purposes and utilize distinct methods to gather and analyze data.

Narrative research designs

The narrative approach in research focuses on the collection and detailed examination of life stories, personal experiences, or narratives to gain insights into individuals' lives as told from their perspectives. It involves constructing a cohesive story out of the diverse experiences shared by participants, often using chronological accounts. It seeks to understand human experience and social phenomena through the form and content of the stories. These can include spontaneous narrations such as memoirs or diaries from participants or diaries solicited by the researcher. Narration helps construct the identity of an individual or a group and can rationalize, persuade, argue, entertain, confront, or make sense of an event or tragedy. To conduct a narrative investigation, it is recommended that researchers follow these steps:

-

Identify if the research question fits the narrative approach. Its methods are best employed when a researcher wants to learn about the lifestyle and life experience of a single participant or a small number of individuals.

-

Select the best-suited participants for the research design and spend time compiling their stories using different methods such as observations, diaries, interviewing their family members, or compiling related secondary sources.

-

Compile the information related to the stories. Narrative researchers collect data based on participants' stories concerning their personal experiences, for example about their workplace or homes, their racial or ethnic culture, and the historical context in which the stories occur.

-

Analyze the participant stories and "restore" them within a coherent framework. This involves collecting the stories, analyzing them based on key elements such as time, place, plot, and scene, and then rewriting them in a chronological sequence (Ollerenshaw & Creswell, 2000). The framework may also include elements such as a predicament, conflict, or struggle; a protagonist; and a sequence with implicit causality, where the predicament is somehow resolved (Carter, 1993).

-

Collaborate with participants by actively involving them in the research. Both the researcher and the participant negotiate the meaning of their stories, adding a credibility check to the analysis (Creswell & Miller, 2000).

Challenges

A narrative investigation includes collecting a large amount of data from the participants and the researcher needs to understand the context of the individual's life. A keen eye is needed to collect particular stories that capture the individual experiences. Active collaboration with the participant is necessary, and researchers need to discuss and reflect on their own beliefs and backgrounds. Multiple questions could arise in the collection, analysis, and storytelling of individual stories that need to be addressed, such as: Whose story is it? Who can tell it? Who can change it? Which version is compelling? What happens when narratives compete? In a community, what do the stories do among them? (Pinnegar & Daynes, 2006).

Phenomenological research designs

A research design based on phenomenology aims to understand the essence of the lived experiences of a group of people regarding a particular concept or phenomenon. Researchers gather deep insights from individuals who have experienced the phenomenon, striving to describe "what" they experienced and "how" they experienced it. This approach to a research design typically involves detailed interviews and aims to reach a deep existential understanding. The purpose is to reduce individual experiences to a description of the universal essence or understanding the phenomenon's nature (van Manen, 1990). In phenomenology, the following steps are usually followed:

-

Identify a phenomenon of interest. For example, the phenomenon might be anger, professionalism in the workplace, or what it means to be a fighter.

-

Recognize and specify the philosophical assumptions of phenomenology, for example, one could reflect on the nature of objective reality and individual experiences.

-

Collect data from individuals who have experienced the phenomenon. This typically involves conducting in-depth interviews, including multiple sessions with each participant. Additionally, other forms of data may be collected using several methods, such as observations, diaries, art, poetry, music, recorded conversations, written responses, or other secondary sources.

-

Ask participants two general questions that encompass the phenomenon and how the participant experienced it (Moustakas, 1994). For example, what have you experienced in this phenomenon? And what contexts or situations have typically influenced your experiences within the phenomenon? Other open-ended questions may also be asked, but these two questions particularly focus on collecting research data that will lead to a textural description and a structural description of the experiences, and ultimately provide an understanding of the common experiences of the participants.

-

Review data from the questions posed to participants. It is recommended that researchers review the answers and highlight "significant statements," phrases, or quotes that explain how participants experienced the phenomenon. The researcher can then develop meaningful clusters from these significant statements into patterns or key elements shared across participants.

-

Write a textual description of what the participants experienced based on the answers and themes of the two main questions. The answers are also used to write about the characteristics and describe the context that influenced the way the participants experienced the phenomenon, called imaginative variation or structural description. Researchers should also write about their own experiences and context or situations that influenced them.

-

Write a composite description from the structural and textural description that presents the "essence" of the phenomenon, called the essential and invariant structure.

Challenges

A phenomenological approach to a research design includes the strict and careful selection of participants in the study where bracketing personal experiences can be difficult to implement. The researcher decides how and in which way their knowledge will be introduced. It also involves some understanding and identification of the broader philosophical assumptions.

Grounded theory research designs

Grounded theory is used in a research design when the goal is to inductively develop a theory "grounded" in data that has been systematically gathered and analyzed. Starting from the data collection, researchers identify characteristics, patterns, themes, and relationships, gradually forming a theoretical framework that explains relevant processes, actions, or interactions grounded in the observed reality. A grounded theory study goes beyond descriptions and its objective is to generate a theory, an abstract analytical scheme of a process. Developing a theory doesn't come "out of nothing" but it is constructed and based on clear data collection. We suggest the following steps to follow a grounded theory approach in a research design:

-

Determine if grounded theory is the best for your research problem. Grounded theory is a good design when a theory is not already available to explain a process.

-

Develop questions that aim to understand how individuals experienced or enacted the process (e.g., What was the process? How did it unfold?). Data collection and analysis occur in tandem, so that researchers can ask more detailed questions that shape further analysis, such as: What was the focal point of the process (central phenomenon)? What influenced or caused this phenomenon to occur (causal conditions)? What strategies were employed during the process? What effect did it have (consequences)?

-

Gather relevant data about the topic in question. Data gathering involves questions that are usually asked in interviews, although other forms of data can also be collected, such as observations, documents, and audio-visual materials from different groups.

-

Carry out the analysis in stages. Grounded theory analysis begins with open coding, where the researcher forms codes that inductively emerge from the data (rather than preconceived categories). Researchers can thus identify specific properties and dimensions relevant to their research question.

-

Assemble the data in new ways and proceed to axial coding. Axial coding involves using a coding paradigm or logic diagram, such as a visual model, to systematically analyze the data. Begin by identifying a central phenomenon, which is the main category or focus of the research problem. Next, explore the causal conditions, which are the categories of factors that influence the phenomenon. Specify the strategies, which are the actions or interactions associated with the phenomenon. Then, identify the context and intervening conditions—both narrow and broad factors that affect the strategies. Finally, delineate the consequences, which are the outcomes or results of employing the strategies.

-

Use selective coding to construct a "storyline" that links the categories together. Alternatively, the researcher may formulate propositions or theory-driven questions that specify predicted relationships among these categories.

-

Develop and visually present a matrix that clarifies the social, historical, and economic conditions influencing the central phenomenon. This optional step encourages viewing the model from the narrowest to the broadest perspective.

-

Write a substantive-level theory that is closely related to a specific problem or population. This step is optional but provides a focused theoretical framework that can later be tested with quantitative data to explore its generalizability to a broader sample.

-

Allow theory to emerge through the memo-writing process, where ideas about the theory evolve continuously throughout the stages of open, axial, and selective coding.

Challenges

The researcher should initially set aside any preconceived theoretical ideas to allow for the emergence of analytical and substantive theories. This is a systematic research approach, particularly when following the methodological steps outlined by Strauss and Corbin (1990). For those seeking more flexibility in their research process, the approach suggested by Charmaz (2006) might be preferable.

One of the challenges when using this method in a research design is determining when categories are sufficiently saturated and when the theory is detailed enough. To achieve saturation, discriminant sampling may be employed, where additional information is gathered from individuals similar to those initially interviewed to verify the applicability of the theory to these new participants. Ultimately, its goal is to develop a theory that comprehensively describes the central phenomenon, causal conditions, strategies, context, and consequences.

Ethnographic research design

An ethnographic approach in research design involves the extended observation and data collection of a group or community. The researcher immerses themselves in the setting, often living within the community for long periods. During this time, they collect data by observing and recording behaviours, conversations, and rituals to understand the group's social dynamics and cultural norms. We suggest following these steps for ethnographic methods in a research design:

-

Assess whether ethnography is the best approach for the research design and questions. It's suitable if the goal is to describe how a cultural group functions and to look into their beliefs, language, behaviours, and issues like power, resistance, and domination, particularly if there is limited literature due to the group’s marginal status or unfamiliarity to mainstream society.

-

Identify and select a cultural group for your research design. Choose one that has a long history together, forming distinct languages, behaviours, and attitudes. This group often might be marginalized within society.

-

Choose cultural themes or issues to examine within the group. Analyze interactions in everyday settings to identify pervasive patterns such as life cycles, events, and overarching cultural themes. Culture is inferred from the group members' words, actions, and the tension between their actual and expected behaviours, as well as the artifacts they use.

-

Conduct fieldwork to gather detailed information about the group’s living and working environments. Visit the site, respect the daily lives of the members, and collect a diverse range of materials, considering ethical aspects such as respect and reciprocity.

-

Compile and analyze cultural data to develop a set of descriptive and thematic insights. Begin with a detailed description of the group based on observations of specific events or activities over time. Then, conduct a thematic analysis to identify patterns or themes that illustrate how the group functions and lives. The final output should be a comprehensive cultural portrait that integrates both the participants (emic) and the researcher’s (etic) perspectives, potentially advocating for the group’s needs or suggesting societal changes to better accommodate them.

Challenges

Researchers engaging in ethnography need a solid understanding of cultural anthropology and the dynamics of sociocultural systems, which are commonly explored in ethnographic research. The data collection phase is notably extensive, requiring prolonged periods in the field. Ethnographers often employ a literary, quasi-narrative style in their narratives, which can pose challenges for those accustomed to more conventional social science writing methods.

Another potential issue is the risk of researchers "going native," where they become overly assimilated into the community under study, potentially jeopardizing the objectivity and completion of their research. It's essential for researchers to be aware of their impact on the communities and environments they are studying.

Case study research design

The case study approach in a research design focuses on a detailed examination of a single case or a small number of cases. Cases can be individuals, groups, organizations, or events. Case studies are particularly useful for research designs that aim to understand complex issues in real-life contexts. The aim is to provide a thorough description and contextual analysis of the cases under investigation. We suggest following these steps in a case study design:

-

Assess if a case study approach suits your research questions. This approach works well when you have distinct cases with defined boundaries and aim to deeply understand these cases or compare multiple cases.

-

Choose your case or cases. These could involve individuals, groups, programs, events, or activities. Decide whether an individual or collective, multi-site or single-site case study is most appropriate, focusing on specific cases or themes (Stake, 1995; Yin, 2003).

-

Gather data extensively from diverse sources. Collect information through archival records, interviews, direct and participant observations, and physical artifacts (Yin, 2003).

-

Analyze the data holistically or in focused segments. Provide a comprehensive overview of the entire case or concentrate on specific aspects. Start with a detailed description including the history of the case and its chronological events then narrow down to key themes. The aim is to look into the case's complexity rather than generalize findings.

-

Interpret and report the significance of the case in the final phase. Explain what insights were gained, whether about the subject of the case in an instrumental study or an unusual situation in an intrinsic study (Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

Challenges

The investigator must carefully select the case or cases to study, recognizing that multiple potential cases could illustrate a chosen topic or issue. This selection process involves deciding whether to focus on a single case for deeper analysis or multiple cases, which may provide broader insights but less depth per case. Each choice requires a well-justified rationale for the selected cases. Researchers face the challenge of defining the boundaries of a case, such as its temporal scope and the events and processes involved. This decision in a research design is important as it affects the depth and value of the information presented in the study, and therefore should be planned to ensure a comprehensive portrayal of the case.

Important reminders when designing a research study

Qualitative and quantitative research designs are distinct in their approach to data collection and data analysis. Unlike quantitative research, which focuses on numerical data and statistical analysis, qualitative research prioritizes understanding the depth and richness of human experiences, behaviours, and interactions.

Qualitative methods in a research design have to have internal coherence, meaning that all elements of the research project—research question, data collection, data analysis, findings, and theory—are well-aligned and consistent with each other. This coherence in the research study is especially critical in inductive qualitative research, where the research process often follows a recursive and evolving path. Ensuring that each component of the research design fits seamlessly with the others enhances the clarity and impact of the study, making the research findings more robust and compelling. Whether it is a descriptive research design, explanatory research design, diagnostic research design, or correlational research design coherence is an important element in both qualitative and quantitative research.

Finally, a good research design ensures that the research is conducted ethically and considers the well-being and rights of participants when managing collected data. The research design guides researchers in providing a clear rationale for their methodologies, which is key to justifying the research objectives to the scientific community. A thorough research design also contributes to the body of knowledge, enabling researchers to build upon past research studies and explore new dimensions within their fields. At the core of the design, there is a clear articulation of the research objectives. These objectives should be aligned with the underlying concepts being investigated, offering a concise method to answer the research questions and guiding the direction of the study with proper qualitative methods.

References

Carter, K. (1993). The place of a story in the study of teaching and teacher education. Educational Researcher, 22(1), 5-12, 18.

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory. London: Sage.

Creswell, J. W., & Miller, D. L. (2000). Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory Into Practice, 39(3), 124-130.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Moustakas, C. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ollerenshaw, J. A., & Creswell, J. W. (2000, April). Data analysis in narrative research: A comparison of two “restoring” approaches. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New Orleans, LA.

Stake, R. E. (1995). The art of case study research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

van Manen, M. (1990). Researching lived experience: Human science for an action sensitive pedagogy. Ontario, Canada: University of Western Ontario.

Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage