- What is Interview Analysis?

- Advantages of Interviews in Research

- Disadvantages of Interviews in Research

- Ethical Considerations in Interviews

- Preparing a Research Interview

- Recruitment & Sampling for Research Interviews

- Interview Design

- How to Formulate Interview Questions

- Rapport in Interviews

- Social Desirability Bias

- Interviewer Effect

- Types of Research Interviews

- Face-to-Face Interviews

- Focus Group Interviews

- Email Interviews

- Telephone Interviews

- Stimulated Recall Interviews

- Interviews vs. Surveys

- Interviews vs Questionnaires

- Interviews and Interrogations

- How to Transcribe Interviews?

- Verbatim Transcription

- Clean Interview Transcriptions

- Manual Interview Transcription

- Automated Interview Transcription

- How to Annotate Research Interviews?

- Formatting and Anonymizing Interviews

- Analyzing Interviews

- Coding Interviews

- Reporting & Presenting Interview Findings

- How to cite "The Guide to Interview Analysis"

Coding Interviews

In qualitative research, coding interviews serve as a crucial method for analyzing and interpreting data, helping researchers identify themes, patterns, and insights within participant responses. Coding allows researchers to systematically categorize information, transforming raw data into structured findings that reveal nuanced understandings of complex topics. This process goes beyond simply labelling content; it requires an interpretive approach that connects data to larger research questions and theoretical frameworks.

Introduction

Through qualitative coding, researchers assign labels or codes to segments of data, which aids in analyzing qualitative data and uncovering patterns or themes. There are several types of coding used in qualitative research, such as thematic analysis, in-vivo coding, process coding, and descriptive coding, each tailored to different research methods and objectives.

While inductive coding emphasizes the discovery of patterns directly from the data, the deductive coding approach relies on predefined codes based on existing theories, ensuring consistency in applying theoretical frameworks. Additionally, methods like theoretical coding and pattern coding help researchers structure their findings and build comprehensive models that explain complex phenomena.

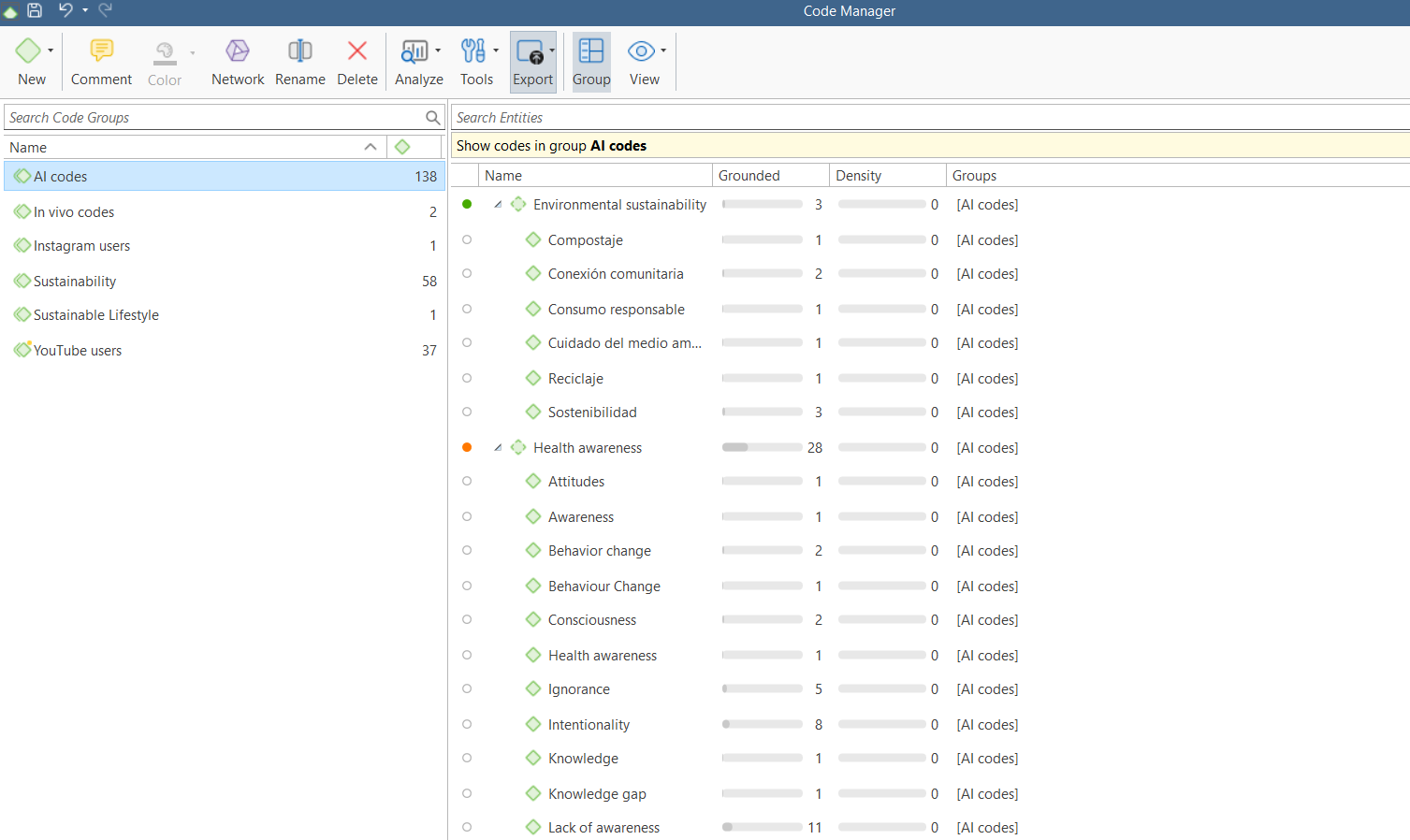

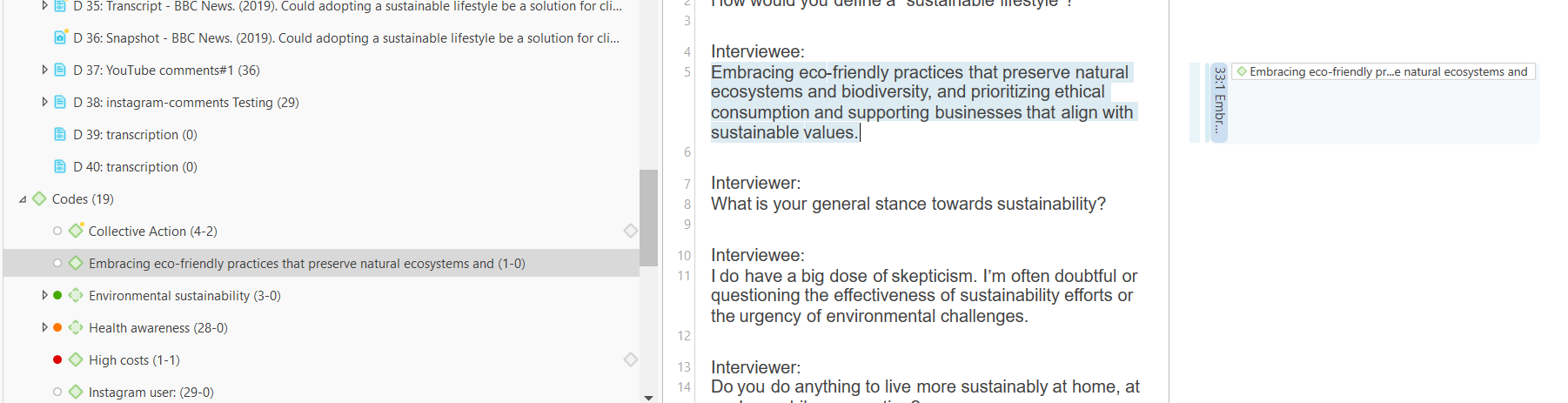

In modern research, qualitative coding has been enhanced by the use of programming languages, which streamline the process, particularly when integrating quantitative data with qualitative insights. These tools make it easier for researchers to write code, automate repetitive tasks, and handle large datasets efficiently. Whether coding interviews or analyzing data from focus groups, the use of digital tools such as ATLAS.ti accelerates the research process, offering greater precision and depth in the final analysis. As a result, researchers can draw more reliable conclusions and insights from their qualitative and quantitative data.

Inductive and deductive coding

Inductive and deductive coding are two essential approaches in qualitative research for analyzing and interpreting data. Each serves a distinct purpose depending on the researcher’s goals, whether generating new insights from data (inductive) or testing existing theories (deductive). Leading scholars have laid the foundation for these methods, shaping how researchers approach data analysis.

Inductive coding

Inductive coding follows a bottom-up approach, where codes and categories emerge directly from the data without a predetermined framework. It is particularly useful for exploratory research, where the goal is to uncover new patterns or generate theories based on participant responses. This approach is closely linked to grounded theory, developed by Glaser and Strauss, which emphasizes that theory should emerge directly from the data through systematic coding (Glaser & Strauss, 1967).

Inductive coding is characterized by its data-driven nature. Codes are created from the content of the data itself, allowing researchers to stay flexible as patterns emerge and evolve. Charmaz (2006), in her constructivist approach to grounded theory, emphasizes the importance of staying close to the data and letting categories form organically as researchers interact with the material.

Example of inductive coding in research: A researcher exploring employee experiences in remote work might begin without any predefined codes. As they analyze interview transcripts, recurring themes like "work-life balance," "technology challenges," and "team communication" might emerge. These themes are then coded and refined into larger categories that could form the basis of new theories about remote work experiences.

When to use inductive coding

- When little is known about the research area, and existing theories are limited.

- When the goal is to generate new insights directly from participants' experiences.

- When flexibility is needed to allow new patterns and categories to emerge.

Deductive coding

Deductive coding, in contrast, is a top-down approach. Researchers begin with a predefined set of codes based on theories, literature, or hypotheses and apply these codes systematically to the data. Deductive coding is often associated with confirmatory research, where the goal is to test the applicability of an existing theory or framework to new data (Bryman, 2001).

This method is characterized by its structured and theory-driven approach, with codes established before data analysis begins. According to Silverman (2001), deductive coding allows for a systematic and rigorous analysis by fitting the data into pre-existing theoretical categories.

Example of deductive coding in research: A study on leadership styles might use predefined codes like "transformational," "transactional," and "laissez-faire," drawn from established leadership theories. As the researcher analyzes interview data, they apply these categories to understand which leadership style best fits the responses.

When to use deductive coding

- When the research is aimed at testing or validating an existing theory.

- When there is substantial prior research or a theoretical framework to guide the analysis.

- When the researcher seeks to maintain consistency across multiple datasets or cases.

Choosing between inductive and deductive coding

The choice between inductive and deductive coding depends on the research goals. Inductive coding is ideal for generating new theories and insights in areas where little is known. Deductive coding is better suited for confirmatory research that aims to test or apply existing frameworks.

A hybrid approach is also commonly used, where researchers may start with deductive coding but remain open to new themes that emerge from the data, integrating inductive coding. This method allows for both testing existing theories and discovering new insights. Creswell (2009) supports using a combination of inductive and deductive approaches, as it offers a more comprehensive analysis by balancing theory testing with the discovery of emergent patterns.

By understanding when to apply inductive or deductive coding, researchers can tailor their approach to fit their specific research objectives, ensuring a thorough and insightful analysis of qualitative data.

Coding Methods

Various established coding methods are frequently used in qualitative research, each contributing uniquely to the analysis process. These methods have been shaped by influential scholars who have developed and refined the coding strategies used today.

Open coding

Open coding is the first step in qualitative data analysis, particularly in grounded theory, where the goal is to break down data into distinct parts and assign labels or "codes" to various segments. This method was introduced by Glaser and Strauss (1967) and is characterized by its open-ended approach, where codes are generated based on the content of the data without any predefined categories.

Process: In open coding, researchers go through the interview transcripts line by line or segment by segment, labelling pieces of data that seem significant. There is no restriction on what can be coded, and the researcher aims to capture as much detail as possible.

Key Characteristics:

- Flexible, exploratory approach.

- Allows for the discovery of new themes and categories directly from the data.

- Aims to be exhaustive, assigning codes to everything potentially relevant.

Example: In interviews about workplace satisfaction, open coding might assign labels like “autonomy,” “team dynamics,” “management style,” or “burnout,” based on the various factors that participants mention.

Open coding is especially useful in early stages of research when the goal is to develop an initial understanding of the data, identifying the range of concepts present. This method often serves as the foundation for more advanced coding methods, such as axial and selective coding.

Thematic coding

Thematic coding, often used in thematic analysis, focuses on identifying and analyzing recurring themes within the data. As described by Braun and Clarke (2006), thematic coding allows researchers to systematically search for patterns across the dataset that are relevant to the research questions.

Process: Researchers go through the data, identifying themes that represent significant ideas or patterns. These themes are then organized and described in relation to the research objectives. Unlike grounded theory, thematic coding does not necessarily aim to build theory but to describe and interpret the data.

Key Characteristics:

- Emphasizes patterns and themes across the dataset.

- Often used for more flexible, descriptive analysis.

- Can be applied inductively (themes emerge from data) or deductively (predefined themes guide analysis).

Example: In interviews about remote work, thematic coding might identify themes such as “work-life balance,” “communication challenges,” and “isolation,” representing the main issues raised by participants.

Thematic coding is popular in qualitative research because it provides an accessible way to organize and interpret data, offering flexibility to explore a variety of issues without the need for a formal theoretical framework.

In vivo coding

In vivo coding uses the exact words or phrases of participants as codes, capturing the language and expressions used by the interviewees themselves. According to Saldaña (2016), in vivo coding is essential for studies where preserving the authenticity of participants' voices is crucial.

Process: Researchers assign codes using direct quotes or specific terms used by participants. This approach ensures that the language and experiences of the participants remain central to the analysis.

Key Characteristics:

- Captures the participant's authentic voice.

- Useful for studies emphasizing participants’ lived experiences.

- Allows for greater focus on the cultural or social context of language.

Example: If a participant in a workplace study repeatedly refers to their job as a “rat race,” the researcher might use “rat race” as a code to capture this particular sentiment.

In vivo coding is commonly used in ethnography, narrative analysis, and other methodologies that prioritize the participant’s perspective and personal experiences.

Process coding

Process coding is ideal for tracking actions, behaviors, or sequences over time, and it is particularly useful in studies focusing on change or procedures. Saldaña (2016) notes that process coding is appropriate for action research, where understanding processes and behaviors is essential.

Process: Researchers use gerunds (verbs ending in “-ing”) to code data, emphasizing ongoing actions, interactions, or behaviors observed in the interviews.

Key Characteristics:

- Focuses on dynamic, action-oriented codes.

- Useful for studies on change, development, or procedural events.

- Captures sequences or stages within the data.

Example: In a study on career development, process coding might involve assigning codes like “seeking mentorship,” “networking,” and “acquiring skills,” representing key actions participants take as they advance in their careers.

Process coding is valuable when the research focuses on understanding sequences or flows of behavior, helping to capture how participants engage in ongoing activities.

Descriptive coding

Descriptive coding, often the first step in qualitative analysis, is used to summarize the basic topic of a segment of data. Described by Miles and Huberman (1994), descriptive coding helps researchers quickly organize large datasets and provides a foundation for more detailed coding processes.

Process: The researcher assigns brief, descriptive labels to each segment of data, summarizing its content without going into deep interpretation.

Key characteristics:

- Provides a basic summary of the data.

- Helps organize large datasets.

- Often serves as a preliminary step before deeper analysis.

Example: In interviews about workplace motivation, descriptive codes might include “salary,” “recognition,” or “career growth,” summarizing the key topics being discussed by participants.

Descriptive coding is particularly useful in the early stages of analysis when researchers need an overview of the content before moving to more complex coding processes.

Coding methods in qualitative research play an essential role in transforming raw interview data into meaningful insights. Whether using open coding to explore new themes, axial coding to identify relationships, or thematic coding to analyze recurring patterns, each method offers a unique approach to understanding qualitative data. Scholars like Glaser, Strauss, Corbin, Braun, Clarke, Saldaña, and Miles have shaped these processes, helping researchers structure and interpret rich, unstructured data systematically. By choosing the appropriate coding method, researchers can derive valuable insights from their interviews, contributing to the broader understanding of their research topic.

Conclusion

Coding interviews in qualitative research is a critical process that helps transform raw data into meaningful insights. Techniques such as thematic analysis, open coding, and axial coding allow researchers to explore and interpret patterns and relationships within the data systematically. These methods provide a structured approach to understanding complex data, whether generating new insights through an inductive coding approach or testing existing frameworks with a deductive coding approach.

The efficiency of coding qualitative data has been greatly enhanced by the use of digital tools and programming languages. Software like ATLAS.ti helps researchers automate and streamline the coding process, making it easier to handle large amounts of data and write code that integrates both qualitative and quantitative data. Whether working with coding interviews or focus groups, these technologies offer greater precision and speed, allowing researchers to derive valuable insights and produce reliable findings. By understanding and applying the appropriate coding techniques, qualitative researchers can significantly enhance the depth and quality of their analysis.

References

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Bryman, A. (2001). Social research methods. Oxford University Press.

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. SAGE Publications.

- Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine.

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.).

- Saldaña, J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Silverman, D. (2001). Interpreting qualitative data: Methods for analyzing talk, text, and interaction (2nd ed.).

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques.