- What is Interview Analysis?

- Advantages of Interviews in Research

- Disadvantages of Interviews in Research

- Ethical Considerations in Interviews

- Preparing a Research Interview

- Recruitment & Sampling for Research Interviews

- Interview Design

- How to Formulate Interview Questions

- Rapport in Interviews

- Social Desirability Bias

- Interviewer Effect

- Types of Research Interviews

- Face-to-Face Interviews

- Focus Group Interviews

- Email Interviews

- Telephone Interviews

- Stimulated Recall Interviews

- Interviews vs. Surveys

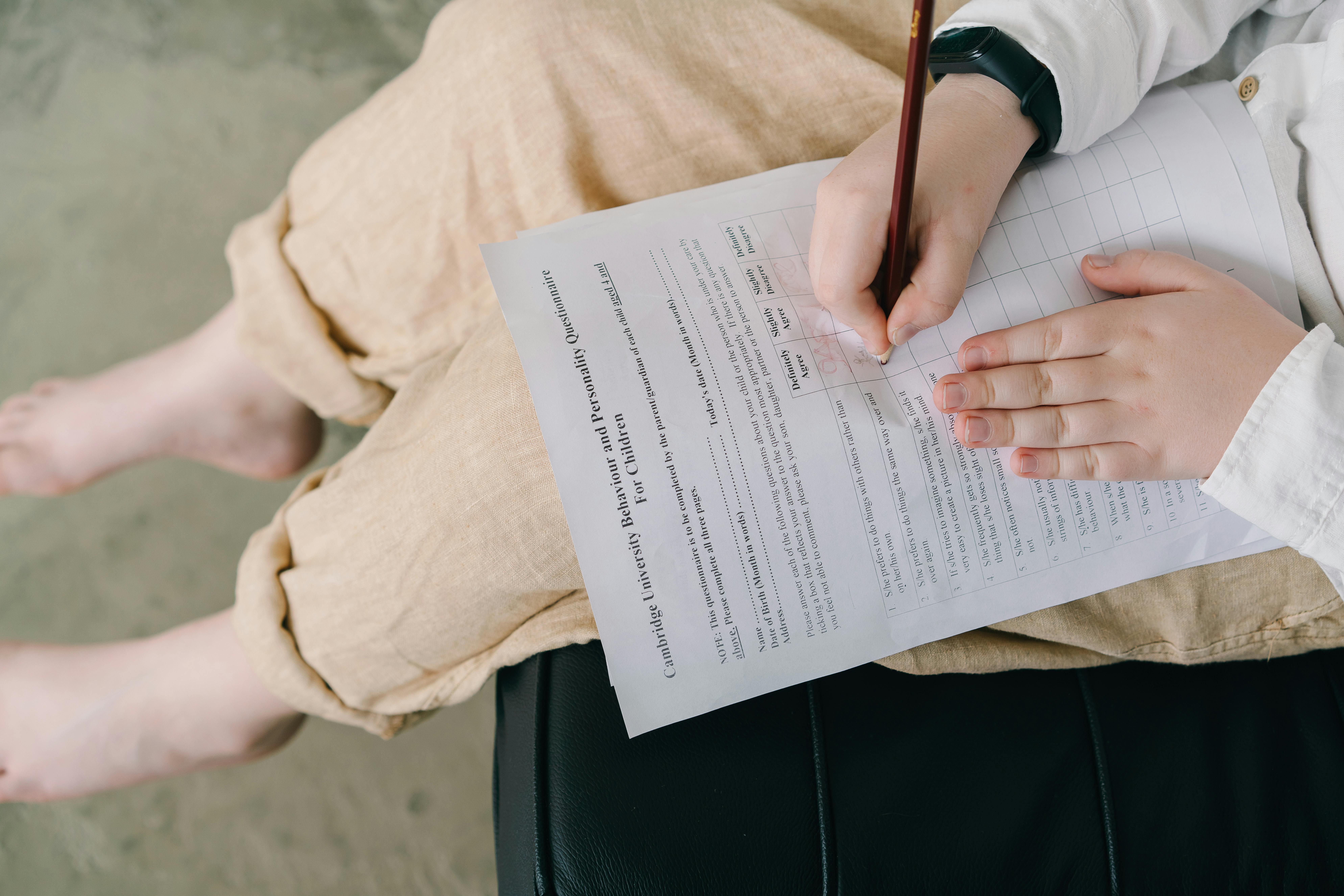

- Interviews vs Questionnaires

- Interviews and Interrogations

- How to Transcribe Interviews?

- Verbatim Transcription

- Clean Interview Transcriptions

- Manual Interview Transcription

- Automated Interview Transcription

- How to Annotate Research Interviews?

- Formatting and Anonymizing Interviews

- Analyzing Interviews

- Coding Interviews

- Reporting & Presenting Interview Findings

- How to cite "The Guide to Interview Analysis"

Interviews vs Questionnaires

Two of the most commonly used methods for gathering primary data are interviews and questionnaires. While both methods aim to collect information, they differ significantly in approach, purpose, and the kind of data they produce. The debate between interviews vs questionnaires often revolves around factors like time, resources, and the depth of understanding they provide. Understanding these differences is essential for researchers who are designing a research project, whether for academic purposes or market research. Read this article to learn more about key differences, challenges and how to choose the right data collection method.

Introduction

Interviews, which can be structured, semi-structured, or unstructured, allow for direct, personal interaction between the researcher and the participant. This method provides an opportunity to explore responses in detail and adapt questions to the flow of the conversation, resulting in rich qualitative data. However, the depth of information collected through interviews comes with a cost: they can be time-consuming and resource-intensive. On the other hand, questionnaires, particularly when delivered through online surveys or mailed forms, offer a more structured and efficient way to gather data from a larger number of respondents. Although questionnaires are often quicker to administer and analyze, they may not provide the same depth or flexibility that interviews offer.

The decision between using interviews vs questionnaires is not always clear-cut. Both methods can yield valuable data, but each has limitations that must be considered when designing your research. In this article, we will explore the key differences between interviews and questionnaires, guide you in choosing the most appropriate data collection method for your research project, and provide best practices to ensure that your data collection process is effective and meaningful. Understanding these distinctions is essential for researchers aiming to collect good quality and relevant data that aligns with their research objectives.

Key differences between interviews and questionnaires

The primary distinction between interviews and questionnaires lies in the type of data they collect and the methods used to collect that data. Interviews, particularly personal interviews, involve direct interaction between the researcher (interviewer) and the respondent. This approach allows the researcher to ask open-ended questions, explore the respondent’s thoughts in depth, and follow up with additional questions if needed. Interviews differ from questionnaires in that they tend to be more time-consuming and resource-intensive.

In contrast, questionnaires typically consist of a written set of questions provided to a large number of respondents. They are often structured as closed-ended questions, although some may include open-ended ones. Questionnaires can be distributed through mail surveys, online platforms, or in person. While they are generally more cost-effective and less time-consuming than interviews, questionnaires may not offer the same level of in-depth understanding of a topic. For example, in an online survey, respondents answer at their own convenience, often resulting in less detailed responses compared to face-to-face interviews.

Choosing the right data collection method

When choosing between interviews and questionnaires, it’s important to consider the research objectives. If the research goal is to gather qualitative data that provides rich, detailed insights, interviews may be the better option. Interviews are ideal for research projects that require an in-depth understanding of the respondent’s experiences, opinions, or behaviors. Qualitative research often relies on personal interviews, focus groups, or semi-structured interviews to delve deeper into topics.

However, if the research requires data from a large number of respondents, questionnaires may be more appropriate. Online surveys, for instance, are useful for collecting quantitative data, which can be statistically analyzed. Questionnaires are especially valuable for large-scale market research, where the researcher aims to gather information from a diverse group of respondents efficiently. Additionally, surveys can be distributed quickly and at a lower cost, making them a more feasible option for researchers with limited available resources.

Mixed methods approaches are becoming increasingly popular in qualitative and quantitative research, combining both interviews and questionnaires to collect comprehensive information. This approach allows researchers to address both the qualitative questions that require open-ended responses and the quantitative questions that demand specific, measurable answers. Combining these data collection methods can offer a more comprehensive understanding of the research topic.

How to make a questionnaire: Length and characteristics

Creating a questionnaire involves careful planning and design to ensure that it captures accurate and meaningful data from respondents. The length and characteristics of a questionnaire depend on the type of research, the target audience, and the specific information you're seeking to gather. Here’s a step-by-step guide on how to create a well-structured questionnaire:

Define the research objectives

Before drafting any questions, clearly define what you want to achieve through the questionnaire. This will help you focus on specific research questions and ensure that your questionnaire is aligned with your research goals. Consider the following:

- What is the main topic or issue you want to explore?

- What specific data do you need to collect?

- Are you gathering qualitative data (opinions, attitudes, etc.) or quantitative data (numbers, statistics)?

Choose the type of questions

Questionnaires typically include two main types of questions: open-ended and closed-ended.

- Closed-ended questions offer predefined answers, such as multiple-choice or Yes/No options. These questions are easier to analyze and are ideal for collecting quantitative data.

- Open-ended questions allow respondents to answer in their own words, providing richer qualitative data. However, they take longer to answer and analyze.

Consider mixing both types, depending on your research needs. For example, you might use closed-ended questions to gather demographic data and open-ended questions to explore opinions or attitudes.

Design clear and concise questions

When creating your questions, clarity and simplicity are key. Avoid complex or double-barreled questions that ask more than one thing at a time. Keep the language simple and free of jargon, ensuring that all respondents understand the questions in the same way. For instance:

- Question: "Do you think the company should invest in employee training and marketing?"

- Improved question: "Do you think the company should invest in employee training?" (Followed by another question about marketing if needed)

Additionally, avoid leading questions that may influence the respondent’s answer. For example, "Don’t you agree that the new product is great?" may bias the respondent. Instead, ask, "What is your opinion of the new product?"

Structure the questionnaire logically

Organize your questions in a logical order that flows naturally for the respondent. Start with simple, non-sensitive questions to ease respondents into the survey. Place demographic or less engaging questions at the end. A common structure includes:

- Introduction: A brief statement explaining the purpose of the questionnaire and instructions for completion. Remember to also ask for consent before recording any responses from participants.

- Main questions: Group questions by topic or theme to make the questionnaire easier to follow. Start with easier to answer questions and then progress to more complex or sensitive questions.

- Demographic questions: These often go at the end to avoid making respondents feel uncomfortable early on, and they often require less energy to answer compared to the main questions.

- Conclusion: Thank respondents for their time and effort. You can also include an open-ended question inviting participants to share any other information they feel is relevant but was not covered in the questionnaire.

Determine the length of the questionnaire

The length of your questionnaire should strike a balance between collecting the necessary data and respecting the respondent's time. Shorter questionnaires (10-15 minutes to complete) generally have higher response rates, while longer questionnaires risk participant drop-off.

- For quantitative studies, aim for around 15-25 closed-ended questions.

- For qualitative or mixed-methods studies, keep open-ended questions to a manageable number (4-6), as these require more time to answer.

Ensure the questionnaire is not too lengthy to prevent respondent fatigue, while remaining comprehensive enough to gather all relevant data. Pilot testing the questionnaire with a small group of people can help determine if the length is appropriate.

Pilot test the questionnaire

Before sending the questionnaire to your full sample, conduct a pilot test with a small group from your target audience. This helps identify any confusing questions, technical issues, or other problems with the questionnaire design. After the pilot test, make necessary revisions based on the feedback.

Characteristics of a good questionnaire

A well-designed questionnaire has the following characteristics:

- Clarity: Questions are easy to understand, and instructions are provided where needed.

- Relevance: Every question serves a clear purpose related to your research objectives.

- Simplicity: Language is straightforward, without technical terms or unnecessary complexity.

- Neutrality: The questionnaire avoids bias and leading questions.

- Logical flow: Questions are organized logically, and sensitive or personal questions are placed appropriately.

- Conciseness: The questionnaire is as short as possible while still collecting all necessary data.

Best practices for effective data collection

To ensure that data collection methods yield quality results, it’s essential to follow best practices. For interviews, one of the most critical aspects is crafting well-designed open-ended questions that encourage the respondent to provide detailed answers. The interview involves building rapport with the respondent, making them comfortable enough to share candid thoughts. Additionally, follow-up questions are crucial for clarifying responses and delving deeper into certain topics that arise during the interview. For example, if a respondent gives a vague answer, the interviewer can ask probing questions to gain more in-depth information.

Questionnaires, on the other hand, require careful design to avoid leading questions that might bias the responses. To gather richer information, the questionnaire can include a mix of open-ended and closed-ended questions. Closed-ended questions are ideal for gathering quantitative data, while open-ended questions allow respondents to provide qualitative data. Including a cover letter with the questionnaire can improve response rates by explaining the purpose of the research and assuring respondents of confidentiality.

Online platforms are increasingly used for surveys and interviews, offering convenience and cost-effectiveness. However, when conducting interviews online, it’s essential to ensure that technical issues, such as poor internet connections, do not hinder the flow of the conversation. When conducting online surveys, researchers should consider the possibility that respondents may misinterpret questions, especially if the questionnaire is lengthy or complex.

Common pitfalls and limitations

While both interviews and questionnaires are valuable tools in data collection, they come with their own limitations. One major drawback of interviews is that they can be highly time-consuming and resource-intensive. Personal interviews, in particular, require scheduling, travelling, and sometimes multiple rounds of follow-up questions. Additionally, there is the risk of socially desirable responses, where respondents provide answers they believe the interviewer wants to hear, rather than their true opinions. This is a common issue in face-to-face interviews.

Questionnaires, while more cost-effective and efficient, also have their pitfalls. One significant limitation is the lack of personal interaction between the researcher and the respondent, which can result in superficial or incomplete responses. The written format of questionnaires does not allow for clarification of ambiguous questions, which can lead to misinterpretations. Another limitation is that questionnaires typically have lower response rates compared to interviews. Mail surveys, for instance, often suffer from low engagement, as respondents may disregard the questionnaire entirely.

Both methods can also introduce bias in the form of leading questions. In an interview, a poorly phrased question can lead the respondent in a particular direction, skewing the data collected. Similarly, in a questionnaire, the wording of questions can inadvertently influence the respondent’s answers. For example, asking, “Don’t you agree that X is true?” can prompt respondents to answer in a way that aligns with the interviewer’s expectations, even if that’s not their genuine belief.

Conclusion

Choosing between interviews and questionnaires is a decision that depends on the research objectives, the type of data needed, and the available resources. Interviews offer a more detailed and personal method for collecting data, but they require more time and resources. On the other hand, questionnaires are more efficient and cost-effective, especially when a large number of respondents is needed, but they may lack the depth that interviews provide.

Researchers can also opt for mixed methods approaches, combining both interviews and questionnaires to gather a more comprehensive set of data. By carefully considering the strengths and weaknesses of each method, researchers can design a data collection strategy that best fits the specific needs of their research project. Whether conducting interviews or distributing questionnaires, the key to successful data collection lies in asking the right questions, following up where necessary, and being aware of the potential limitations of each method.