- Handling qualitative data

- Transcripts

- Field notes

- Memos

- Survey data and responses

- Visual and audio data

- Data organization

- Data coding

- Coding frame

- Auto and smart coding

- Organizing codes

- Qualitative data analysis

- Content analysis

- Thematic analysis

- Narrative research

- Phenomenological research

- Discourse analysis

- Grounded theory

- Deductive reasoning

- Inductive reasoning

- Inductive vs. deductive reasoning

- Qualitative data interpretation

- Qualitative data analysis software

- How to cite "The Ultimate Guide to Qualitative Research - Part 2"

- Thematic analysis vs. content analysis

Grounded theory

Among the various approaches to qualitative data analysis, grounded theory is among those that stay very close to the data to develop a theory. Grounded theory analysis is essential, particularly in research inquiries where there is little or no existing theory, to guide the organization of knowledge from data collection.

Let's look at the topic of grounded theory methodology by exploring its rationale, its potential for theory development, the steps employed in grounded theory procedures, and how ATLAS.ti can facilitate grounded theory methods.

What is grounded theory in simple terms?

Barney G. Glaser and Anselm L. Strauss are credited with developing grounded theory as a widely-used research methodology in qualitative analysis in the social sciences. Over the decades, other researchers, such as Kathy Charmaz, have further developed grounded theory approaches. Glaser and Strauss broke new ground in qualitative inquiry through grounded theory by arguing against any notions that science had maximized its potential for developing new theory. As a result, the primary purpose of grounded theory is to construct theories grounded in systematically gathered and analyzed data rather than beginning with a preconceived theory. The ultimate goal is to generate a theory that offers an explanation of the research question that stems from what emerges from the data.

What is the main point of grounded theory?

At its core, grounded theory is about the discovery of new concepts and relationships. Rather than starting research with a theory and then testing it, grounded theory researchers begin with an area of study and allow what is relevant in that area to emerge. The methodology was developed as a response to the traditional approach of having a hypothesis before conducting research, which can lead to forcing the data to meet preconceived notions. The main point of grounded theory is to cultivate an understanding of social phenomena from the perspective of those experiencing them.

When should you use grounded theory research?

Grounded theory research is appropriate when there is little prior information or established theory about a phenomenon. It is most suitable for investigations of processes, actions, and interactions. Grounded theory can be particularly useful in exploratory studies where the aim is to identify key issues, explore them in detail, and construct a model or theory that can be used to understand the phenomenon from a new perspective.

You might choose to use grounded theory when you want to learn about people's experiences, their perceptions of these experiences, and the actions they take as a result. The inductive nature of grounded theory makes it suitable for studying social processes over time, understanding the changes and development of a phenomenon, and gaining in-depth insights from the perspective of those directly involved.

Benefits of using grounded theory

One of the key advantages of using grounded theory is that it promotes the emergence of new theories and deepens our understanding of the social world around us. Here are some of the key benefits:

- Flexibility: Grounded theory is adaptive and can be adjusted during the research process, providing a degree of flexibility not often seen in other research methods.

- Inductive nature: Because it is inductive, grounded theory is well suited for discovering how individuals interpret their experiences and the world around them.

- Rich, detailed insights: Grounded theory's focus on the exploration of phenomena can lead to rich, detailed insights and in-depth understanding.

- Practical outcomes: Grounded theory generates theory and provides practical implications that can inform policy, intervention, or program development.

Limitations of grounded theory

While grounded theory offers many advantages, it is essential to be aware of its limitations:

- Time-consuming: The process of data collection and analysis can be time-consuming due to the method's iterative nature.

- Complexity: The method can be complex to apply correctly due to its abstract concepts and the various stages of coding and analysis.

- Requires skill and experience: Successful implementation of grounded theory requires strong analytical skills and experience in qualitative research.

- Subjectivity: While subjectivity can be a strength in understanding the experiences of others, it can also be a limitation if biases are not properly acknowledged and managed.

Core components of grounded theory

Grounded theory, as a research methodology, consists of several core components that guide the research process, from data collection to the development of a final theoretical framework. These components are interrelated, each influencing and shaping the others in a dynamic, iterative process. The core components of grounded theory include theoretical sensitivity, theoretical sampling, coding and analysis, theoretical saturation, and theoretical integration.

Theoretical sensitivity

Theoretical sensitivity refers to a researcher's ability to understand and define phenomena in terms of their underlying patterns or structures. It's an acquired skill that grows with experience, through exposure to literature, professional experiences, and personal experiences. It's about being sensitive to the nuances and complexities of the data, understanding the subtle cues or messages, and being able to pull these together to form a coherent understanding. Theoretical sensitivity can be developed in many ways. Reading and engaging with relevant literature, attending workshops or seminars, conducting preliminary interviews or observations, or even through casual conversations related to the research topic, can help to increase a researcher's theoretical sensitivity. It is about having a sense of what is important in the data, what to pay attention to, and what can be given less importance.

Theoretical sampling

Theoretical sampling is the process of data collection driven by the emerging theory. Instead of having a predefined sample at the start of the research, grounded theorists allow their theoretical ideas to guide them in selecting new data sources to explore. This iterative process means that data collection and analysis occur simultaneously, and both are influenced by the emerging theory. Theoretical sampling can be quite challenging for new researchers as it requires a level of flexibility and openness that is not typically found in more structured research designs. The researcher needs to be comfortable with uncertainty and willing to follow the data wherever it may lead.

Coding and analysis

Coding and analysis are key processes in grounded theory, consisting of several stages. The first step is open coding, where the researcher examines the data in a detailed and line-by-line manner to identify initial concepts. The focus is on breaking down the data into discrete parts and closely examining them for their underlying meaning. The next stage is axial coding, where the researcher begins to assemble the data in new ways after the initial breakdown during open coding. The aim is to identify relationships between the initial codes and to group them into more abstract categories. The final stage is selective coding, where the researcher integrates and refines the categories to form a cohesive theoretical framework. Unlike in thematic analysis where the goal is often simply to outline the dimensions of a phenomenon, the focus here is on developing a unifying theory around which all other categories are related.

Theoretical saturation

Theoretical saturation is a critical concept in grounded theory. It refers to the point at which no new insights or concepts are being found in the data, indicating that the categories are well-developed and that further data collection is unnecessary. Saturation doesn't mean that every single aspect of the data has been explored but rather that the categories within the theory are robust and comprehensive. The concept of saturation is tied closely to the idea of theoretical sampling. As the theory begins to take shape, the researcher focuses their data collection on areas that will help to further develop or refine their emerging categories.

Theoretical integration

Theoretical integration is the final stage in grounded theory. It involves pulling together all the categories that have been developed, linking them together, and integrating them into a cohesive and coherent theory. Integration also involves a process of validation, where the researcher returns to their data and checks that their theory fits and explains the data. At this stage, it's important that the researcher is able to explain their theory clearly and convincingly, showing how it offers a new and insightful understanding of the phenomenon they have studied.

Detailed steps in grounded theory research

The research process in grounded theory consists of a series of interconnected and iterative steps. Each step is part of a holistic process designed to allow a theory to emerge from the data inductively. The process of constant comparison, also known as the constant comparative method or constant comparative analysis, is central to this process. Here, we'll walk through these steps in detail.

Data collection

The first step in grounded theory research is data collection. Data can come from various sources such as interviews, observations, documents, or any other source relevant to the research question. The form of data collection can vary greatly, and the selection depends largely on the nature of the research question and the context of the study. It's important to note that in grounded theory, data collection is an iterative process and continues throughout the entire research process. Initial data collection informs the early stages of analysis and the emerging theory, which then guides further data collection. This back-and-forth between data collection and analysis is a distinguishing feature of grounded theory.

Open coding

After some data has been collected, the process of open coding begins. This is the first step in the constant comparative method. During open coding, the researcher carefully reads and re-reads the data, breaking it down into discrete incidents or ideas. Each of these incidents is then given a code - a word or short phrase that represents the essence of that piece of data. Open coding is a line-by-line analysis, which means that every line of the data is scrutinized and potentially given a code. It's during this process that the researcher starts to see categories and properties emerge from the data.

The open coding process is also where constant comparison begins. As each piece of data is coded, it's compared to other data coded in the same way. This comparison process allows the researcher to refine the definitions of codes and begin to see patterns and relationships.

Axial coding

The next step in the grounded theory process is axial coding. This stage of the constant comparative method involves taking the initial categories developed during open coding and beginning to see how they relate to each other.

During axial coding, the researcher is constantly comparing data within a category, as well as comparing categories to each other. This process allows for more abstract thinking about the data. It helps to identify central phenomena, contexts, conditions, strategies, and consequences - elements that help to give a structure to the emerging theory.

Selective coding

Selective coding is the final stage of constant comparative analysis. At this point, the researcher has a clear idea of the main categories and how they relate to each other. The goal of selective coding is to integrate these categories around a central, core category. This core category represents the main theme or process that the theory explains.

During selective coding, the researcher is still using constant comparison, but the focus is now on making sure that all categories are connected to the core category and that all categories are well-developed. This stage of the research process ends when theoretical saturation is reached - when no new data appears to add to the understanding of the core category.

Writing the theory

The final step in grounded theory research is to write up the theory. This is an important part of the process because it's where the researcher takes the abstract ideas that have been developed and turns them into a concrete, coherent theory.

Writing the theory involves clearly defining the core category, explaining how other categories relate to the core, and demonstrating how the theory explains the process or phenomena under study. The result is a well-integrated set of theoretical concepts that can offer new insights into the research question.

Role of the researcher in grounded theory

The researcher plays a critical role in grounded theory. They are not a passive observer but an active participant in the research process. From data collection to analysis to theory formation, the researcher's perspectives, experiences, and interpretive skills significantly shape the research process and outcomes. This section discusses the role of the researcher in grounded theory, including aspects of objectivity and subjectivity, as well as the importance of reflective practice.

Objectivity and subjectivity in research

In grounded theory research, the objectivity and subjectivity of the researcher are both significant considerations. Objectivity refers to the ability to conduct research in a neutral, unbiased manner. On the other hand, subjectivity acknowledges the researcher's personal experiences, backgrounds, and perspectives that they bring to the study.

In grounded theory, researchers aim for a balance between these two. While striving for objectivity helps foster the study's credibility, it's also important to recognize and consider the subjectivity of the researcher. It's this subjectivity that allows the researcher to interpret the data, relate to the participants, and understand the phenomenon in depth. Researchers should be transparent about their assumptions, biases, and preconceptions. Acknowledging these factors not only aids reflexivity but also contributes to the credibility and trustworthiness of the research.

Importance of reflective practice

Reflective practice is a cornerstone of grounded theory methodology. It involves the researcher critically reflecting on their own role in the research process and the impact they may have on the data collection, analysis, and theory formation. Through reflective practice, researchers become more aware of their own assumptions and perspectives and can better understand how these elements might influence their research.

Reflective practice takes place throughout the research process. During data collection, researchers might reflect on their interactions with participants, considering how their questions, demeanor, or reactions might influence the responses. During data analysis, reflective practice helps researchers understand how their preconceptions and interpretations shape the coding and emerging theory.

In grounded theory, reflective practice is not a linear step but a continuous process that loops back and forth throughout the research. It's through this reflective practice that researchers can build a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the phenomenon under study.

Role of the researcher in data collection and analysis

In grounded theory, the researcher is considered the primary tool of data collection and analysis. This is different from quantitative research, where data collection tools are often standardized questionnaires or tests.

As the primary tool of data collection, the researcher is involved in interviewing participants, observing behavior, and gathering documents or other artifacts. The researcher must be skilled in establishing rapport with participants, asking insightful questions, and carefully observing and noting details.

In terms of data analysis, the researcher's intellectual capacity, intuition, and creativity play a crucial role. The process of coding data, recognizing patterns, developing categories, and forming an overarching theory heavily relies on the researcher's analytical skills. Moreover, their ability to critically reflect on their own role and influence in the research process is vital to ensure the study's trustworthiness.

When carefully considering where they stand in any qualitative study, especially in a grounded theory study, the researcher should carefully reflect on their thinking and methods. Reflexivity is a process where researchers continuously evaluate and reflect upon their entire research process and their role within it. Researchers need to be conscious of their potential influence on the research and actively work to verify their conclusions. Maintaining a research diary, where thoughts, ideas, and reflections can be recorded throughout the study, is a common strategy used to promote reflexivity.

Constructivist grounded theory

Grounded theory has evolved since its original inception by sociologists Barney Glaser and Anselm Strauss in the 1960s. One significant development is constructivist grounded theory, an approach that emphasizes the interpretive aspects of knowledge creation. This approach, most notably propagated by Kathy Charmaz, views research as a co-construction of knowledge between the researcher and the participants. Let's examine the foundations of constructivist grounded theory and the associated constructivist grounded theory methods.

Foundation of constructivist grounded theory

Constructivist grounded theory stems from the philosophical perspective of constructivism, which asserts that reality is socially constructed and subjective. Constructivists believe that people construct their own understanding of the world based on their experiences and interactions. Applying this viewpoint to grounded theory, constructivist grounded theorists argue that researchers and participants co-construct the data and the ensuing analysis. Hence, the researcher is not an objective observer but an active participant in the research process, contributing their interpretations and perspectives.

Key characteristics of constructivist grounded theory

There are several key characteristics that differentiate constructivist grounded theory from its traditional counterpart. These include the emphasis on researcher-participant interaction, the recognition of multiple realities, the focus on interpretive understanding, and the flexible use of grounded theory methods.

- Emphasis on researcher-participant interaction: Constructivist grounded theory acknowledges that data doesn't exist in a vacuum. It's produced through interactions between the researcher and the participant. These interactions are dynamic, context-dependent, and mutually influential, contributing to the co-construction of knowledge.

- Recognition of multiple realities: In line with constructivist philosophy, this approach recognizes the existence of multiple realities. Each participant and the researcher have their unique interpretation of reality, informed by their experiences, values, and social contexts.

- Focus on interpretive understanding: Constructivist grounded theory prioritizes interpretive understanding. Rather than seeking an objective truth, this approach aims to understand how individuals interpret and make sense of their experiences.

- Flexible use of grounded theory methods: While constructivist grounded theory maintains the core grounded theory methods, such as coding and theoretical sampling, it's more flexible in its use. The emphasis is on using these methods as tools to facilitate understanding rather than rigid steps to be followed.

Constructivist grounded theory methods

The process of conducting a constructivist approach to grounded theory study largely mirrors the steps of traditional grounded theory, albeit with a greater emphasis on reflexivity and the interpretive role of the researcher.

Data collection in constructivist grounded theory often involves in-depth interviews, observations, and document analysis, with the researcher actively engaging with the participants to co-construct the data. During the analysis, the researcher remains reflexive about their interpretations and assumptions, constantly checking them against the data.

Coding in constructivist grounded theory still involves open, axial, and selective coding, but the process is more flexible and intuitive. The researcher uses their insights and perspectives to guide the coding process, constantly comparing the data and remaining open to multiple interpretations.

The ultimate goal of constructivist grounded theory is to generate an interpretive theory that makes sense of the participants' experiences and actions. This theory is not seen as a concrete truth but a context-dependent, co-constructed interpretation of the phenomenon under study.

What tools will help with grounded theory?

While this section has focused on the philosophical and methodological dimensions of grounded theory research, it's also important to think about what tools might be useful for researchers involved in conducting a grounded theory study. Previously in this guide, we have explored how ATLAS.ti can aid you in coding your data. That said, there are additional tools in qualitative data analysis and especially in ATLAS.ti that can facilitate the grounded theory coding and analysis process.

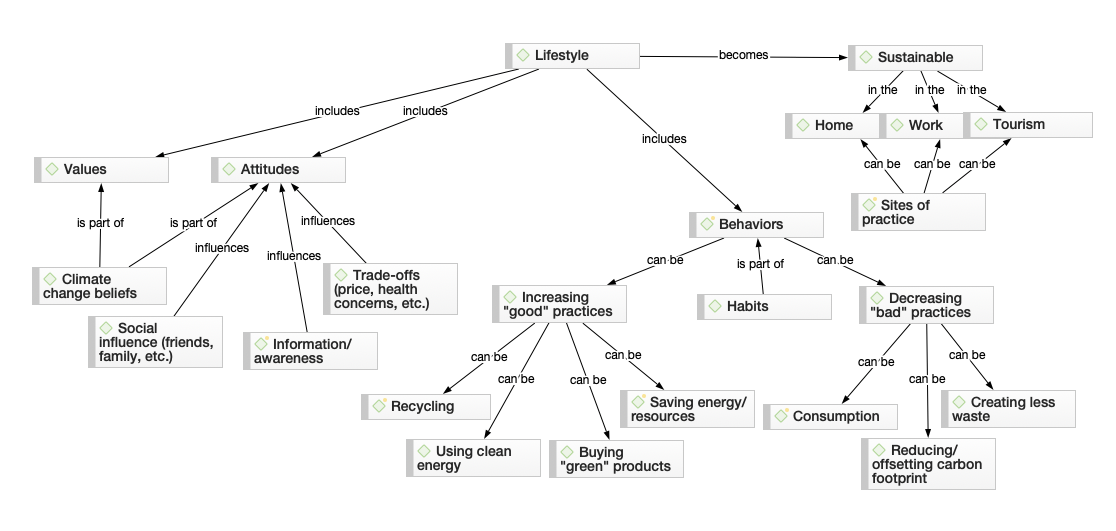

Networks

The axial coding stage of grounded theory, which deals with theoretical development, shifts the focus of data analysis from coding discrete instances of data to drawing connections between those codes. The researcher is responsible for identifying relationships between discrete phenomena that might have otherwise been thought of as unrelated to each other. Without such relationships, there would be no foundation for developing a novel theory relevant to the social world. Moreover, the sorting of knowledge and information cannot be done, nor can scientific knowledge be easily retrieved and understood, without visualizing these networks of social phenomena.