- Handling qualitative data

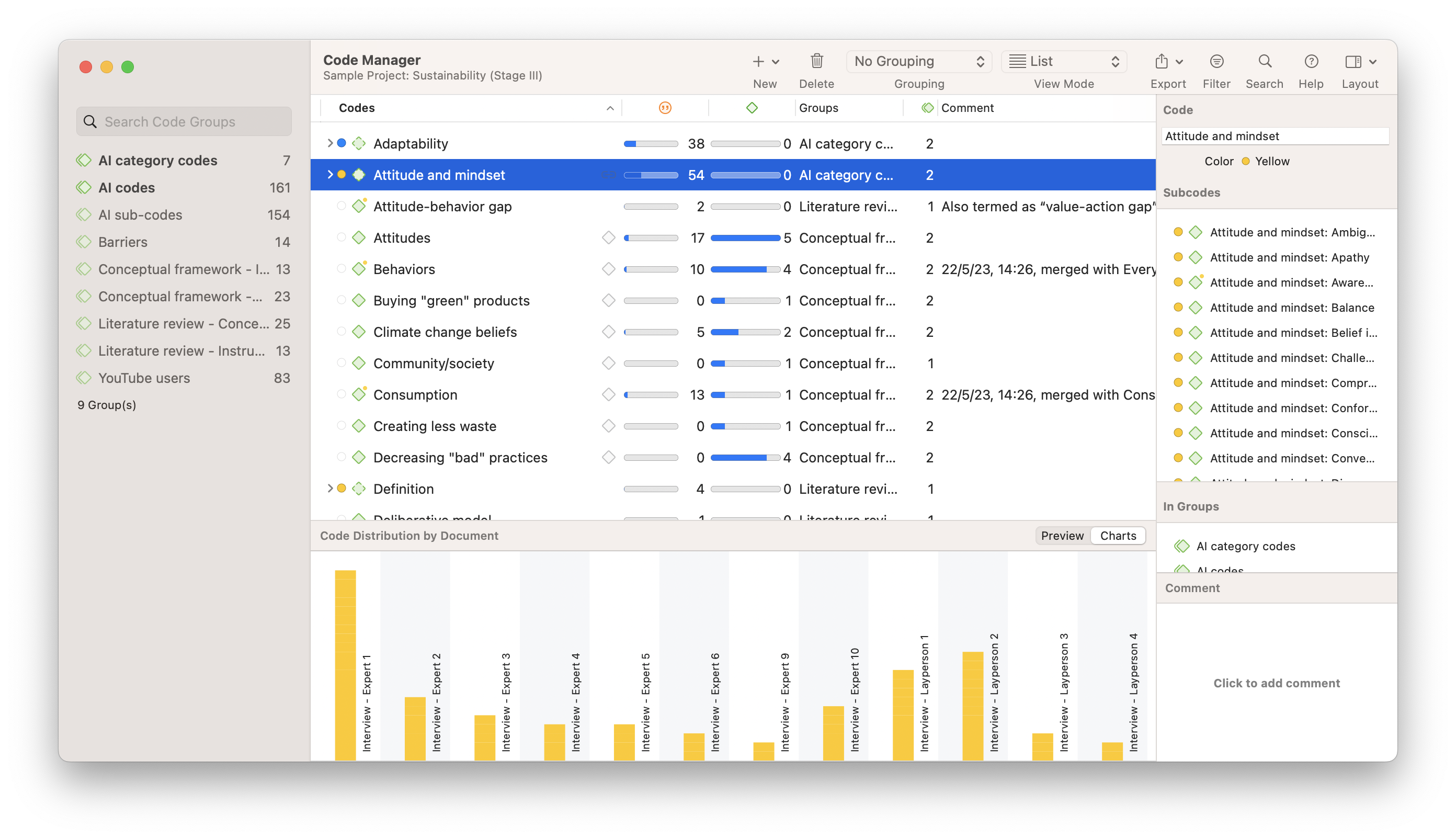

- Transcripts

- Field notes

- Memos

- Survey data and responses

- Visual and audio data

- Data organization

- Data coding

- Coding frame

- Auto and smart coding

- Organizing codes

- Qualitative data analysis

- Content analysis

- Thematic analysis

- Narrative research

- Phenomenological research

- Discourse analysis

- Grounded theory

- Deductive reasoning

- Inductive reasoning

- Inductive vs. deductive reasoning

- Qualitative data interpretation

- Qualitative data analysis software

- How to cite "The Ultimate Guide to Qualitative Research - Part 2"

- Thematic analysis vs. content analysis

Inductive reasoning and analysis

If you conduct research inductively, you derive a theory from your observations. A quantitative study can follow up an inductive analysis to substantiate an observation to generalize your theory to a population.

Inductive reasoning is an analytical approach that involves proposing a broader theory about the research topic based on the data that you use in your study. Inductive reasoning is a bottom-up approach where researchers construct knowledge and propose new theory that emerges from the data.

Inductive and deductive reasoning goes hand in hand to allow researchers to develop a theoretical understanding of the human and social world. Let's look more closely at the concept of inductive reasoning and how it applies to research and in ATLAS.ti.

Inductive logic

When people make specific observations about a particular phenomenon and draw conclusions based solely on the substance of those observations, they engage in a form of reasoning called inductive logic. Those conclusions can serve their working theory until other specific observations challenge or contradict their understanding.

They must then further develop their understanding into a more nuanced and coherent conclusion that accommodates their broadened observations of the world. Ultimately, the inductive method aims to construct a theory that explains relationships among the studied concepts or phenomena.

Inductive reasoning examples

Inductive reasoning becomes easier to understand as a bottom-up approach to logic. To take an example from everyday life, if one were to see a cat, notice that it has a tail, and come across other creatures that have tails, then they can reach a generalized conclusion through inductive reference based on their observations: all animals with a tail are cats.

Obviously, this does not mean that the proposed theory is the end of the inductive reasoning process. They can find a dog with a tail, but they would be hard-pressed to call it a cat.

As a result, the theory they have developed from previous experience could provide a better explanation. That person would have to conduct new observations of cats and dogs to make a further inductive inference: cats and dogs have tails, but cats have sharper claws. The cycle of inductive reasoning can thus continue indefinitely to identify patterns and develop more robust theories.

Another famous example is that of the black swan. You can inductively conclude that all swans are white if you have only observed white swans so far.

This theory must be thrown out when you encounter a black swan. Then you need to revise your theory to account for the new observation.

What is inductive reasoning?

The role of inductive reasoning in research is not always readily apparent if you only look at experimental research as a means for developing theory. Experimental research depends on deductive reasoning to confirm or dispute an existing theory, while inductive reasoning is most associated with observations and interviews.

Observation and inductive logic are most appropriate in research inquiries where the existing theory is not sufficiently developed or developed at all, requiring researchers to develop an inductive explanation about the phenomenon they are studying.

Especially in social science research, it's impossible to come to a necessarily final conclusion to the inductive reasoning process. Knowledge is always in constant development thanks to research.

Objective of inductive reasoning

The objectives of the inductive approach are to build theories from a set of data that allow researchers to make a general statement about a phenomenon while also opening up new lines of inquiry for future research.

It is also important to note that inductive research need not exist independent of existing theory. The research process always calls for connections to the existing literature to organize and generate knowledge. The main principle in applying inductive reasoning to your research is that the inferences you establish come from the data you analyze.

Is inductive analysis qualitative or quantitative?

Inductive reasoning is often associated with qualitative research, where the objective is to examine contexts, processes, or meanings that are not easily quantifiable. Quantitative analysis, on the other hand, tends to rely on deductive reasoning to test existing theories to suggest when established knowledge requires further development.

That said, inductive reasoning skills can be used with quantitative methods to form hypotheses based on the data. The important premise of an inductive approach is that propositions and theories are generated from the patterns of a phenomenon in a particular body of data.

Frequencies and themes

Patterns that occur in abundance across observations or interviews may be useful in developing theory. In addition, qualitative researchers may also identify patterns or themes that appear only once or twice but that shed important light on the phenomenon under study.

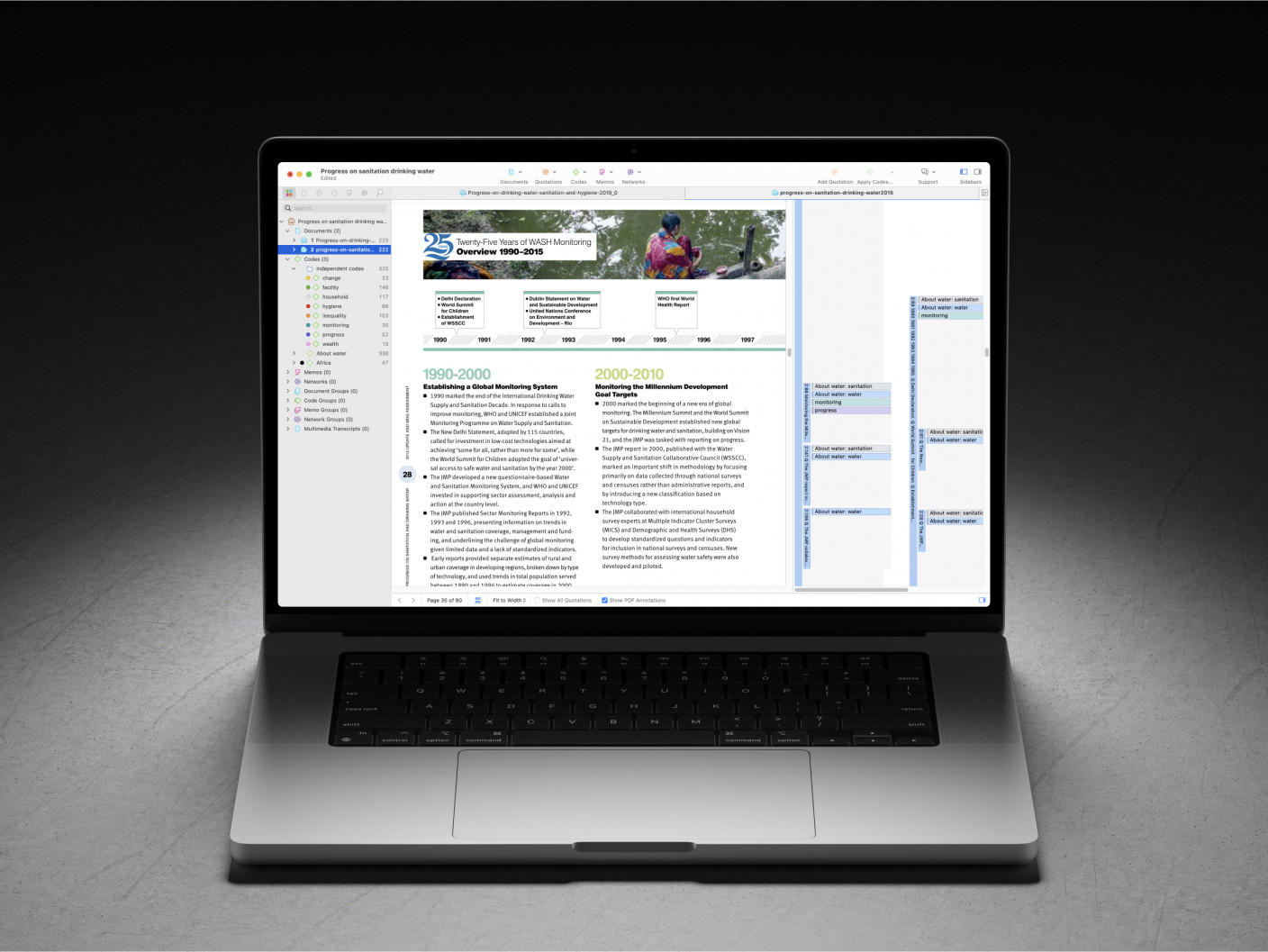

ATLAS.ti, for example, has tools such as the Word Cloud to count the frequency of words. If you use a transcript of a speech, you can employ the Word Cloud tool and apply inductive reasoning to make a logical conclusion about a speaker's speech patterns based on the words they use most often.

Inductive vs. deductive reasoning

Deductive and inductive research are contrasting but complementary approaches used in scientific work. To clarify the difference, deductive approaches examine theoretical inferences from the top to bottom, while inductive methods aim to generate theoretical inferences from the bottom up. In other words, deductive reasoning works with current facts, while inductive reasoning seeks to create a new set of facts.

Looking at cats and dogs

To return to the example about cats and dogs, an example of a deductive inference would be one that uses an existing conclusion that all cats have tails and sharp claws. As a result, if someone finds an animal with a tail and sharp claws, they can employ deductive reasoning based on the above conclusion to call that animal a cat. Naturally, the more refined the theories employed, the more a researcher can rely on deductive reasoning.

The two approaches are not mutually exclusive and can be combined in the same scientific study. You can, for instance, build a code system starting with some deductively derived concepts, which you enrich throughout the analysis process with codes that you develop from the data inductively. In this sense, inductive and deductive reasoning both contribute to the analysis of your research.

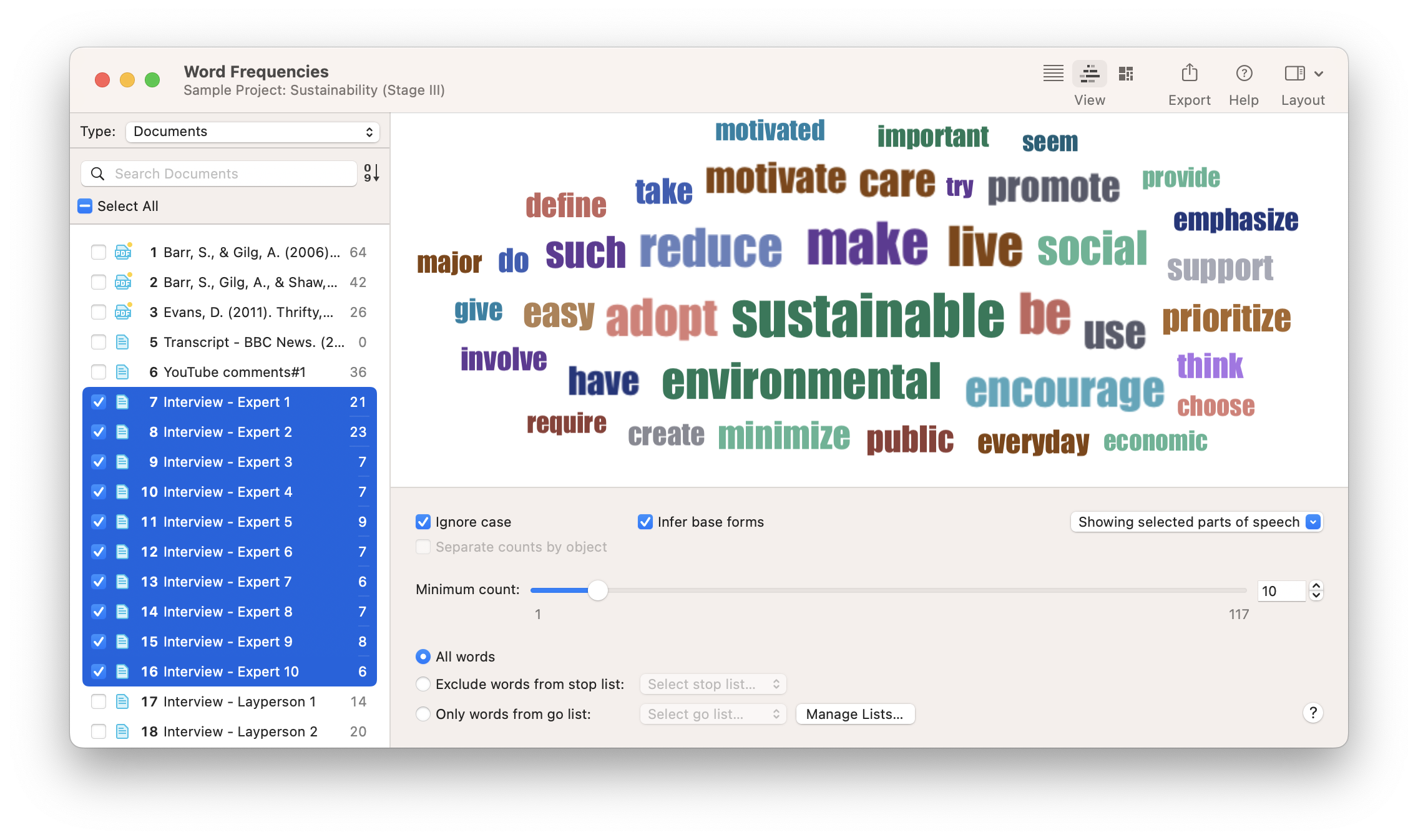

You can use the Code Manager in ATLAS.ti to differentiate between the two sets of codes to organize inductive and deductive approaches in the same project. Colors and code groups can help you distinguish between the different kinds of codes you use to conduct your analysis.

For more complex research projects, smart codes can also facilitate the organization of your research by identifying segments of data that meet a certain set of criteria based on your codes.

The inductive approach in the research process

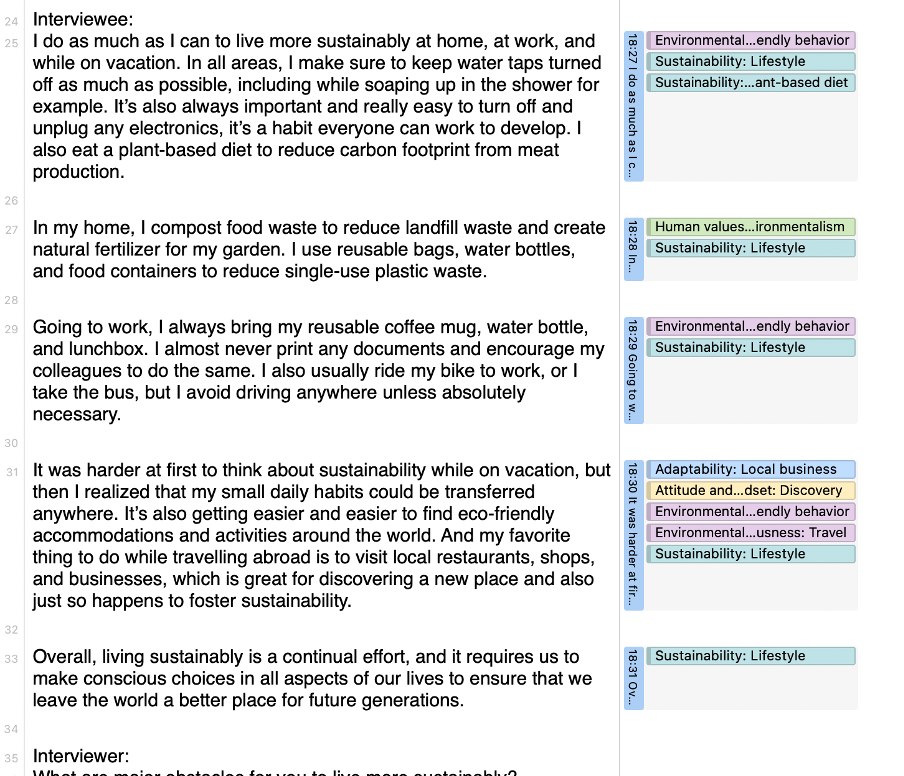

The research process can often be divided into data collection and data analysis. In qualitative research, coding is typically the intermediary step that facilitates analysis, moving you forward in developing conclusions and explaining them using theories.

Data collection

Inductive reasoning can be applied to most methods of data collection. That said, qualitative research methods that call for observations or interactions with research participants allow the researcher to employ inductive reasoning during data collection.

Imagine an interview project to determine the effects of social media usage. In initial interviews with people, the researcher may notice that many respondents mention physical effects like eye strain or lack of sleep. When the researcher believes there is a connection, they may adjust the questions they ask respondents to find more evidence of this causal relationship.

Similarly, with observations, a researcher employs inductive reasoning when they notice something that occurs frequently. For example, they might notice that people using smartphones in public tend to get in more accidents (e.g., bumping into others or tripping over objects). As a result, they can adjust their observations by going to crowded places where it is more likely people using smartphones might suffer more accidents.

Coding

An inductive reasoning approach to qualitative data analysis requires looking at your project to identify key segments of data that will ultimately serve as the premises for your development of theory. The theory can be further developed after identifying patterns and adjusting the focus to look for more evidence of or exceptions to those patterns.

In ATLAS.ti, the process for employing an inductive approach starts with looking at your data. What patterns seem apparent? What shows up in the data? What instances of data appear most relevant to your research inquiry?

Give each pattern a short but descriptive label that forms one of your codes. Codes are short because they help summarize large segments for quick understanding or to categorize discrete segments in separate areas of your research project.

These codes can be created directly in the Code Manager, or you may find it easier to create codes while reading the data. As you read through your project, you can create new codes and then apply them to segments of data that are called quotations. Quotations given the same code can be said to be related to each other by the same broader pattern, thus establishing connections between different data segments with the same code.

As an example of this relationship, imagine you are coding a set of documents that contain people's schedules in everyday life. These schedules might mention activities such as "tennis practice," "doctor's appointment," and "movie night with partner." Looking at these schedules, you might want to apply codes such as "fun activities" and "important tasks" to these items to get a sense of how often each category of activity occurs in people's everyday routines.

Auto-coding

Coding your data can be a time-consuming process, but required when applying inductive reasoning to your research data. Traditionally, researchers code one document, or source of data, at a time.

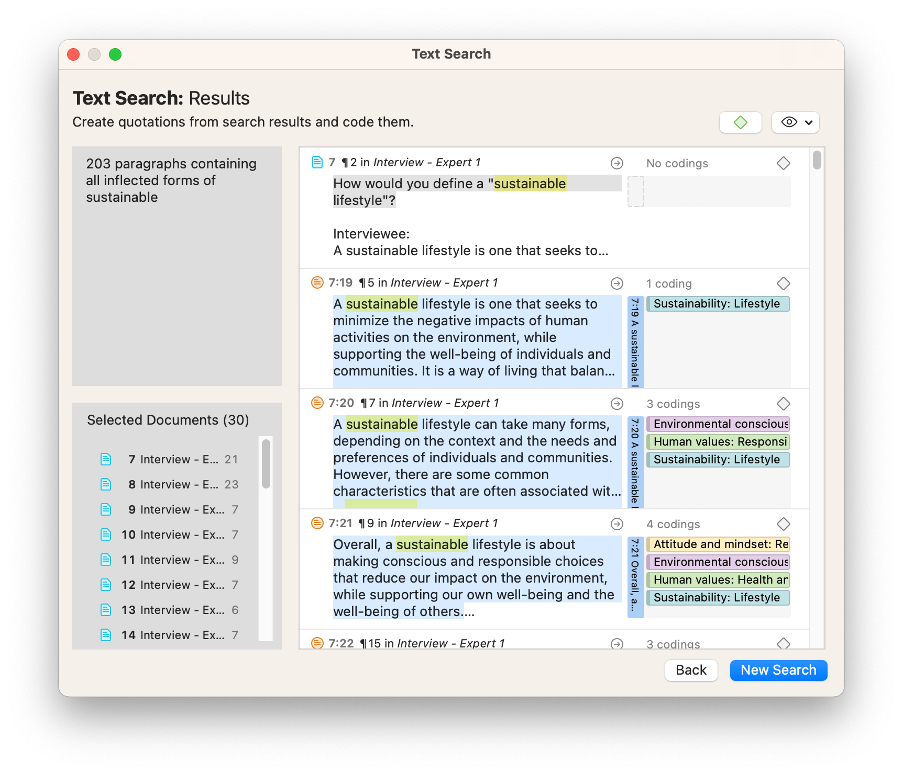

In ATLAS.ti, tools like the Text Search function can quicken the coding process by allowing researchers to search for a specific word or phrase in their project and code segments containing their desired search term. If a particular code can be represented by a certain word or phrase, the Text Search tool can allow you to organize the relevant data in one place for quick and easy coding. You can use the Word Cloud to inductively identify specific words or phrases and then code for these using the Text Search tool.

The Text Search function also works with deductive reasoning, particularly when existing theories can be associated with particular words or phrases you can look for in your project. Whatever the approach, ATLAS.ti can help you save time in coding your research.

Further data analysis

Once your data has been coded, you can look at the Code Manager to examine which codes have been used the most. This will aid the inductive reasoning process by identifying what occurs the most often in your data.

Not only can you apply inductive reasoning through the occurrence of codes, but also the co-occurrence of codes as well. Keep in mind that quotations can contain multiple codes and that quotations with different codes can overlap.

When text is associated with more than one code, those codes co-occur with each other. Researchers can use that co-occurrence to infer relationships between different phenomena.

ATLAS.ti has a tool called Code Co-Occurrence Analysis, where you can examine codes generated through inductive reasoning and identify potential relationships between those codes. The Code Co-Occurrence table lists the frequencies for different pairs of codes that you specify in ATLAS.ti.

Drawing conclusions

Codes based on inductive reasoning are often brought together into a theory or framework. You can look at both frequently occurring codes as well as codes that appear even only once or twice to build premises for your theory. What is most important is that the different parts of your theory fit together in a coherent manner and explain the phenomenon under study. Building conclusions relies on first drawing tentative conclusions and then verifying these conclusions in the data. You might adjust your conclusions as you find different examples or disconfirming evidence. This iterative process contributes to building a meaningful theory or framework.

Frequencies of code co-occurrence represent potential relationships between codes that are potentially useful to theoretical development. The frequency counts for codes and code co-occurrences can all be exported into Microsoft Excel using ATLAS.ti's export functions. By exporting these counts into a spreadsheet, researchers can then run further statistical analysis on their project. More complex statistical analyses can also be conducted by exporting the entire ATLAS.ti project and importing it into a statistical analysis software, such as SPSS or R.

Further inquiry

A more holistic research inquiry can start with inductive research methods but should look at different approaches to research in order to fully understand a particular concept or phenomenon. You may want to collect data for deductive research to apply your theories developed through inductive reasoning to new information, or you may look at abductive reasoning to look at your object of inquiry in an entirely new way. Synthesizing your research with a quantitative approach may also be useful if you are looking to identify any statistical generalization in your research inquiry. Whatever your research, however, you can benefit from addressing your research questions from multiple angles.

Abductive reasoning

While the use of deductive versus inductive approaches in research is often discussed, abductive reasoning is the third type of reasoning that also warrants some attention.

Abductive reasoning can be seen as sitting between inductive and deductive forms of reasoning. Abduction involves developing an argument based on the information available in your data and then verifying or further elaborating on these inductive findings by referring to existing theories. Iterating between data and literature thus informs abductive analysis.

Employing quantitative research

Theories built on inductive reasoning can be followed up by quantitative research to confirm the research through statistical generalizations. Generally, any research that employs deductive reasoning can be used to support inductive inferences. Still, quantitative research at scale is useful in confirming the applicability of theory across large populations or multiple contexts.

Regardless of the reasoning or methodology employed, all good research has the capability of generating, strengthening, and extending theory when it incorporates sound, transparent analysis. ATLAS.ti can facilitate the analytical process of research by making the coding process faster and more intuitive so that researchers can spend more time critically reflecting on their analysis and developing theory.