What is the Significance of Validity in Research?

- Introduction

- What is validity in simple terms?

- Internal validity vs. external validity in research

- Uncovering different types of research validity

- Factors that improve research validity

Introduction

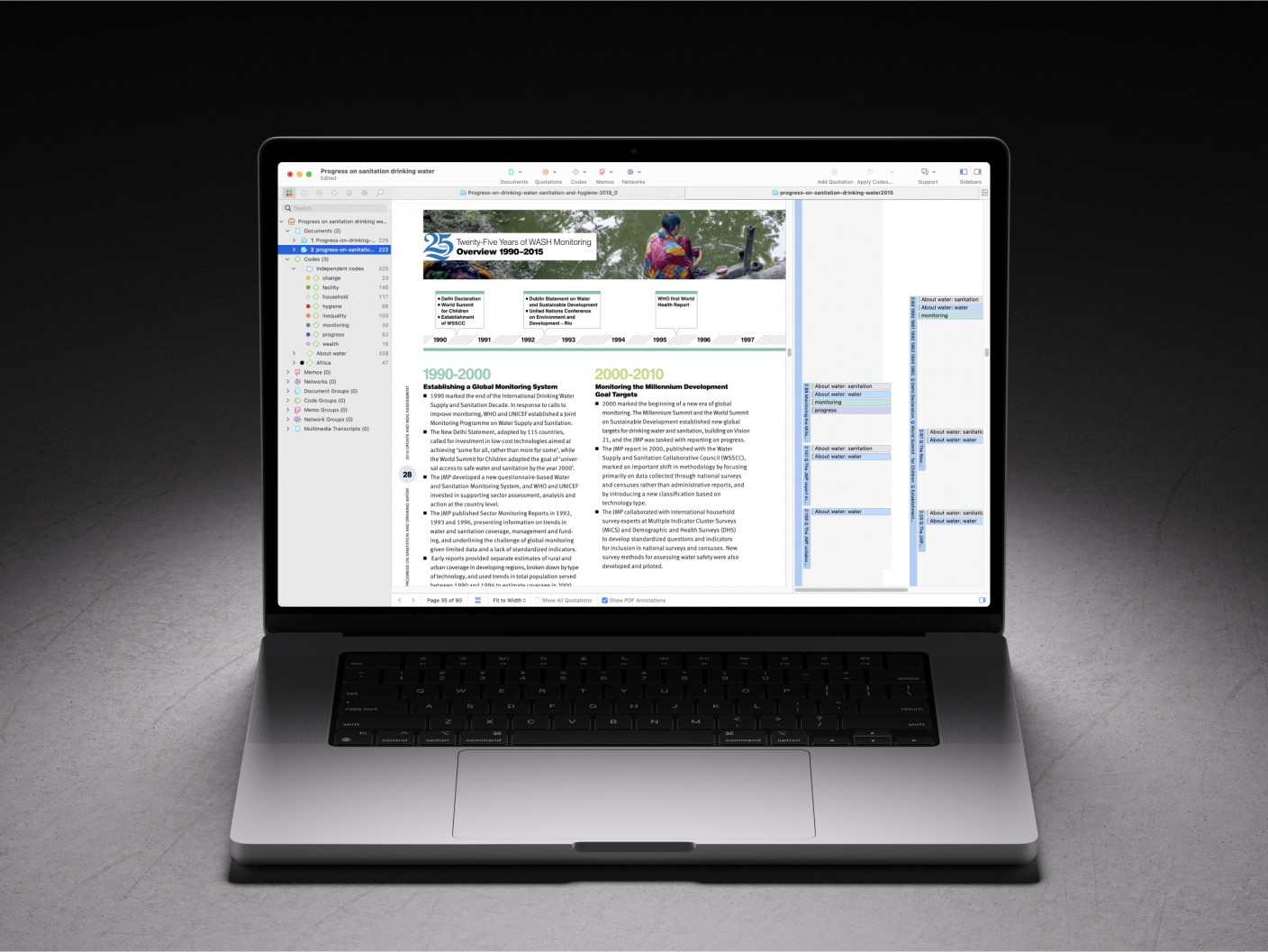

In qualitative research, validity refers to an evaluation metric for the trustworthiness of study findings. Qualitative research, with its rich, narrative-driven investigations, demands unique criteria for ensuring validity.

Unlike its quantitative counterpart, which often leans on numerical robustness and statistical veracity, the essence of validity in qualitative research informs the credibility, dependability, and richness of the data.

The importance of validity in qualitative research cannot be overstated. Establishing validity refers to ensuring that the research findings genuinely reflect the phenomena they are intended to represent. It reinforces the researcher's responsibility to present an authentic representation of study participants' experiences and insights.

This article will examine validity in qualitative research, exploring its characteristics, techniques to bolster it, and the challenges that researchers might face in establishing validity.

At its core, validity in research speaks to the degree to which a study accurately reflects or assesses the specific concept that the researcher is attempting to measure or understand. It's about ensuring that the study investigates what it purports to investigate. While this seems like a straightforward idea, the way validity is approached can vary greatly between qualitative and quantitative research.

Quantitative research often hinges on numerical, measurable data. In this paradigm, validity might refer to whether a specific tool or method measures the correct variable, without interference from other variables. It's about numbers, scales, and objective measurements. For instance, if one is studying personalities by administering surveys, a valid instrument could be a survey that has been rigorously developed and tested to verify that the survey questions are referring to personality characteristics and not other similar concepts, such as moods, opinions, or social norms.

Conversely, qualitative research is more concerned with understanding human behavior and the reasons that govern such behavior. It's less about measuring in the strictest sense and more about interpreting the phenomenon that is being studied. The questions become: "Are these interpretations true representations of the human experience being studied?" and "Do they authentically convey participants' perspectives and contexts?"

Differentiating between qualitative and quantitative validity is important because the research methods to ensure validity differ between these research paradigms. In quantitative realms, validity might involve test-retest reliability or examining the internal consistency of a test.

In the qualitative sphere, however, the focus shifts to ensuring that the researcher's interpretations align with the actual experiences and perspectives of their subjects.

This distinction is fundamental because it impacts how researchers engage in research design, gather data, and draw conclusions. Ensuring validity in qualitative research is like weaving a tapestry: every strand of data must be carefully interwoven with the interpretive threads of the researcher, creating a cohesive and faithful representation of the studied experience.

Internal validity vs. external validity in research

While often terms associated more closely with quantitative research, internal and external validity can still be relevant concepts to understand within the context of qualitative inquiries. Grasping these notions can help qualitative researchers better navigate the challenges of ensuring their findings are both credible and applicable in wider contexts.

Internal validity

Internal validity refers to the authenticity and truthfulness of the findings within the study itself. In qualitative research, this might involve asking: Do the conclusions drawn genuinely reflect the perspectives and experiences of the study's participants?

Internal validity revolves around the depth of understanding, ensuring that the researcher's interpretations are grounded in participants' realities. Techniques like member checking, where participants review and verify the researcher's interpretations, can bolster internal validity.

External validity

External validity refers to the extent to which the findings of a study can be generalized or applied to other settings or groups. For qualitative researchers, the emphasis isn't on statistical generalizability, as often seen in quantitative studies. Instead, it's about transferability.

It becomes a matter of determining how and where the insights gathered might be relevant in other contexts. This doesn't mean that every qualitative study's findings will apply universally, but qualitative researchers should provide enough detail (through rich, thick descriptions) to allow readers or other researchers to determine the potential for transfer to other contexts.

Uncovering different types of research validity

It's important to recognize and understand the various types of validity and their distinctions. Each type offers distinct criteria and methods of evaluation, ensuring that research remains robust and genuine. Here's an exploration of some of these types.

Construct validity

Construct validity is a cornerstone in research methodology. It pertains to ensuring that the tools or methods used in a research study genuinely capture the intended theoretical constructs.

In qualitative research, the challenge lies in the abstract nature of many constructs. For example, if one were to investigate "emotional intelligence" or "social cohesion," the definitions might vary, making them hard to pin down.

To bolster construct validity, it is important to clearly and transparently define the concepts being studied. In addition, researchers may triangulate data from multiple sources, ensuring that different viewpoints converge towards a shared understanding of the construct. Furthermore, they might undergo into iterative rounds of data collection, refining their methods with each cycle to better align with the conceptual essence of their focus.

Content validity

Content validity's emphasis is on the breadth and depth of the content being assessed. In other words, content validity refers to capturing all relevant facets of the phenomenon being studied. Within qualitative paradigms, ensuring comprehensive representation is especially important. If, for instance, a researcher is using interview protocols to understand community perceptions of a local policy, the questions should encompass all relevant aspects of that policy. This could range from its implementation and impact to public awareness and opinion variations across demographic groups.

Enhancing content validity can involve expert reviews where subject matter experts evaluate tools or methods for comprehensiveness. Another strategy might involve pilot studies, where preliminary data collection reveals gaps or overlooked aspects that can be addressed in the main study.

Ecological validity

Ecological validity refers to the genuine reflection of real-world situations in research findings. For qualitative researchers, this means their observations, interpretations, and conclusions should resonate with the participants and context being studied.

If a study explores classroom dynamics, for example, studying students and teachers in a controlled research setting would have lower ecological validity than studying real classroom settings. Ecological validity is important to consider because it helps ensure the research is relevant to the people being studied. Individuals might behave entirely different in a controlled environment as opposed to their everyday natural settings.

Ecological validity tends to be stronger in qualitative research compared to quantitative research, because qualitative researchers are typically immersed in their study context and explore participants' subjective perceptions and experiences. Quantitative research, in contrast, can sometimes be more artificial if behavior is being observed in a lab or participants have to choose from predetermined options to answer survey questions.

Qualitative researchers can further bolster ecological validity through immersive fieldwork, where researchers spend extended periods in the studied environment. This immersion helps them capture the nuances and intricacies that might be missed in brief or superficial engagements.

Face validity

Face validity, while seemingly straightforward, holds significant weight in the preliminary stages of research. It serves as a litmus test, gauging the apparent appropriateness and relevance of a tool or method. If a researcher is developing a new interview guide to gauge employee satisfaction, for instance, a quick assessment from colleagues or a focus group can reveal if the questions intuitively seem fit for the purpose.

While face validity is more subjective and lacks the depth of other validity types, it's only an initial step, ensuring that the research starts on the right foot.

Criterion validity

Criterion validity evaluates how well the results obtained from one method correlate with those from another, more established method. In many research scenarios, establishing high criterion validity involves using statistical methods to measure validity. For instance, a researcher might utilize the appropriate statistical tests to determine the strength and direction of the linear relationship between two sets of data.

If a new measurement tool or method is being introduced, its validity might be established by statistically correlating its outcomes with those of a gold standard or previously validated tool. Correlational statistics can estimate the strength of the relationship between the new instrument and the previously established instrument, and regression analyses can also be useful to predict outcomes based on established criteria.

While these methods are traditionally aligned with quantitative research, qualitative researchers, particularly those using mixed methods, may also find value in these statistical approaches, especially when wanting to quantify certain aspects of their data for comparative purposes. More broadly, qualitative researchers could compare their operationalizations and findings to other similar qualitative studies to assess that they are indeed examining what they intend to study.

Factors that improve research validity

In qualitative research, the role of the researcher is not just that of an observer but often as an active participant in the meaning-making process. This unique positioning means the researcher's perspectives and interactions can significantly influence the data collected and its interpretation. Here's a deep dive into the researcher's role in upholding validity.

Reflexivity

A key concept in qualitative research, reflexivity requires researchers to continually reflect on their worldviews, beliefs, and potential influence on the data. By maintaining a reflexive journal or engaging in regular introspection, researchers can identify and address their own biases, ensuring a more genuine interpretation of participant narratives.

Building rapport

The depth and authenticity of information shared by participants often hinge on the rapport and trust established with the researcher. By cultivating genuine, non-judgmental, and empathetic relationships with participants, researchers can enhance the validity of the data collected.

Positionality

Every researcher brings to the study their own background, including their culture, education, socioeconomic status, and more. Recognizing how this positionality might influence interpretations and interactions is beneficial to research. By acknowledging and transparently sharing their positionality, researchers can offer context to their findings and interpretations.

Active listening

The ability to listen without imposing one's own judgments or interpretations is key. Active listening ensures that researchers capture the participants' experiences and emotions without distortion, enhancing the validity of the findings.

Transparency in methods

To ensure validity, researchers should be transparent about every step of their process. From how participants were selected to how data was analyzed, a clear documentation offers others a chance to understand and evaluate the research's authenticity and rigor.

Member checking

Once data is collected and interpreted, revisiting participants to confirm the researcher's interpretations can be invaluable. This process, known as member checking, ensures that the researcher's understanding aligns with the participants' intended meanings, bolstering validity.

Embracing ambiguity

Qualitative data can be complex and sometimes contradictory. Instead of trying to fit data into preconceived notions or frameworks, researchers must embrace ambiguity, acknowledging areas of uncertainty or multiple interpretations.