How to Conduct Effective Pilot Tests: Tips and Tricks

- Introduction

- What is the main purpose of pilot testing?

- What qualitative research approaches rely on a pilot test?

- What are the benefits of a pilot study?

- How do you conduct a pilot study?

- Steps after evaluation of pilot testing

Introduction

Successful qualitative research projects often begin with an essential step: pilot testing. Similar to beta testing for computer programs and online services, a pilot test, sometimes referred to as a small-scale preliminary study or pilot study, is to trial a design on a smaller scale before embarking on the main study.

Whether the focus is psychiatric research, a randomized controlled trial, or any other project, conducting a pilot test provides invaluable data, allowing research teams to refine their approach, optimize their evaluation criteria, and better predict the outcomes of a full-scale project.

What is the main purpose of pilot testing?

Pilot testing, or the act of conducting a pilot study, is an important phase in the research process, especially in qualitative and social science research. It serves as a preparatory step, a preliminary test, allowing researchers to evaluate, refine, and if necessary, redesign aspects of their study before full implementation, as well as determine the cost of a full study.

Pilot studies for assessing feasibility

One of the most significant purposes of a pilot test is to assess the feasibility of and identify potential design issues in the main study. It provides insights into whether a study's design is practical and achievable.

For instance, a research team might find that the originally planned method of interviewing is too time-consuming for a larger study or that participants may not be as forthcoming as hoped. Such insights from a feasibility study can save time, effort, and resources in the long run.

During pilot testing, a researcher can also determine how many or what kinds of participants might be needed for the main study to achieve meaningful results. It helps in ensuring that the target population is adequately represented without overwhelming the team with excessive data.

Refining research methods

A pilot study with a small sample size offers a testing ground for the instruments, tools, or techniques that the researchers plan to use.

For example, suppose a project involves using a new interview technique. In that case, the pilot group can provide feedback on the clarity of questions, the flow of the interview, or even the comfort level of the interaction. This feedback from a carefully selected group can contribute to refining the tools and methods to ensure that the main study captures the richest insights possible.

No design is perfect from the outset. Pilot testing acts as a litmus test, highlighting any potential challenges or issues that might arise during the full-scale project.

By identifying these hurdles in advance, researchers can preemptively devise solutions, ensuring smoother execution when the full study is conducted.

Gathering preliminary data

While the primary aim of pilot testing is not necessarily data collection for the main study, the knowledge garnered can be incredibly valuable for improving the current study or building toward a future study.

During the pilot phase of a research project, patterns, anomalies, or unexpected results can emerge. These can lead researchers to refine their propositions or research objectives, adjusting them to better align with observed realities.

Beyond its direct application to the design of the research, the initial findings from a pilot study can have broader, more strategic uses. When seeking funding for a full-scale project, having tangible results, even if they're preliminary, can lend credibility and weight to a research proposal.

Demonstrating that a concept has been tested, even on a small scale, and has yielded insightful data can make a compelling case to potential sponsors or stakeholders.

What qualitative research approaches rely on a pilot test?

Pilot studies are a foundational component of many approaches in qualitative research. The exploratory and interpretative nature of qualitative methodologies means that research tools and strategies often benefit from preliminary testing to ensure their effectiveness.

In ethnographic research, where the goal is to study cultures and communities in-depth, pilot studies help researchers become familiar with the environment and its people. A brief preliminary visit can aid in understanding local dynamics, forging initial relationships, and refining methods to respect cultural sensitivities.

Grounded theory research, which seeks to develop theories grounded in empirical data, often starts with pilot studies. These preliminary tests aid in refining the interview protocols and sampling strategies, ensuring that the main study captures data that genuinely represents and informs the emerging theory.

Narrative research relies on the collection of stories from individuals about their experiences. Given the depth and nuance of personal narratives, a pilot test can be instrumental in determining the most effective ways to prompt and capture these stories while ensuring participants feel comfortable and understood.

Phenomenological research, which endeavors to understand the essence of participants' lived experiences around a phenomenon, often employs pilot testing to refine interview questions. It ensures that these questions elicit detailed, rich descriptions of experiences without leading or influencing the participants' responses.

In the field of case study research, where a particular case (or a few cases) is studied in-depth, pilot studies can help in delineating the boundaries of the case, deciding on the data collection methods, and anticipating potential challenges in data gathering or interpretation.

Lastly, psychiatric research, which looks into understanding mental processes, behaviors, and disorders, frequently employs pilot studies, especially when introducing new therapeutic techniques or interventions. A small-scale preliminary study can help identify any potential risks or issues before applying a new method or tool more broadly.

What are the benefits of a pilot study?

A pilot study, being a precursor to the main research, can provide valuable insight to the researcher. These initial investigations through pilot studies, while smaller in scale, can prove consequential in terms of benefits they offer to the research process.

Ensuring methodological rigor

At its core, a pilot study is a testing ground for the tools, techniques, and strategies that will be employed in the main study. By test-driving these elements, you can identify weaknesses or areas of improvement in the methodology.

This helps in ensuring that when the full future study is conducted, the methods used are sound, reliable, and capable of yielding meaningful results. For instance, if an interview question consistently confuses participants during the pilot phase, you can revise it for clarity in the main study.

Optimizing resource allocation

One of the significant advantages of pilot testing is the potential for resource optimization. You can gain insights into the time, effort, and funds required for various activities, allowing for more accurate budgeting and scheduling.

Moreover, by preempting potential challenges or obstacles, a pilot study can prevent costly mistakes or oversights when scaling up to the full research. For example, discovering that a particular method is inefficient during the pilot phase can save countless hours and resources in the larger study.

Enhancing participant experience and ethical considerations

The qualitative researcher often examines participants' personal experiences, emotions, and perceptions for rich data. A pilot study provides an opportunity to ensure that the research process is respectful, sensitive, and ethically sound.

By trialing interactions with a smaller group, those who conduct the study can refine their approach to ensure participants feel valued, understood, and comfortable. This not only enhances the quality of the insights collected but also fosters trust and rapport with the research subjects.

In sum, the benefits of conducting a pilot study extend far beyond mere preliminary testing. They fortify the research process, ensuring studies are rigorous, efficient, and ethically sound.

How do you conduct a pilot study?

A pilot study is an integral phase in the process, acting as a bridge between initial study design and the full-scale project by providing information for future guidance. To generate actionable insights and pave the way for a successful full study, there are key steps researchers need to follow.

Defining objectives and scope

Before diving into the pilot study, it's essential to clearly define its objectives. What specific aspects of the main study are you testing? Is it the data collection methods, the feasibility of the research design of the study, or the clarity of the interview questions?

When researchers answer these questions, they can gain insight on whether the pilot study remains manageable and yields specific, actionable insights from a completed pilot.

Selecting a representative sample

For a pilot study to be effective, the sample chosen should be a good representation of the target population. This doesn't mean it needs to be large; after all, it's a small-scale preliminary study.

However, it should capture the diversity and characteristics of the population to provide a realistic preview of how the research might unfold. Think about how your selected group addresses the needs of your study and evaluate whether their contributions to the research can help you answer your research questions.

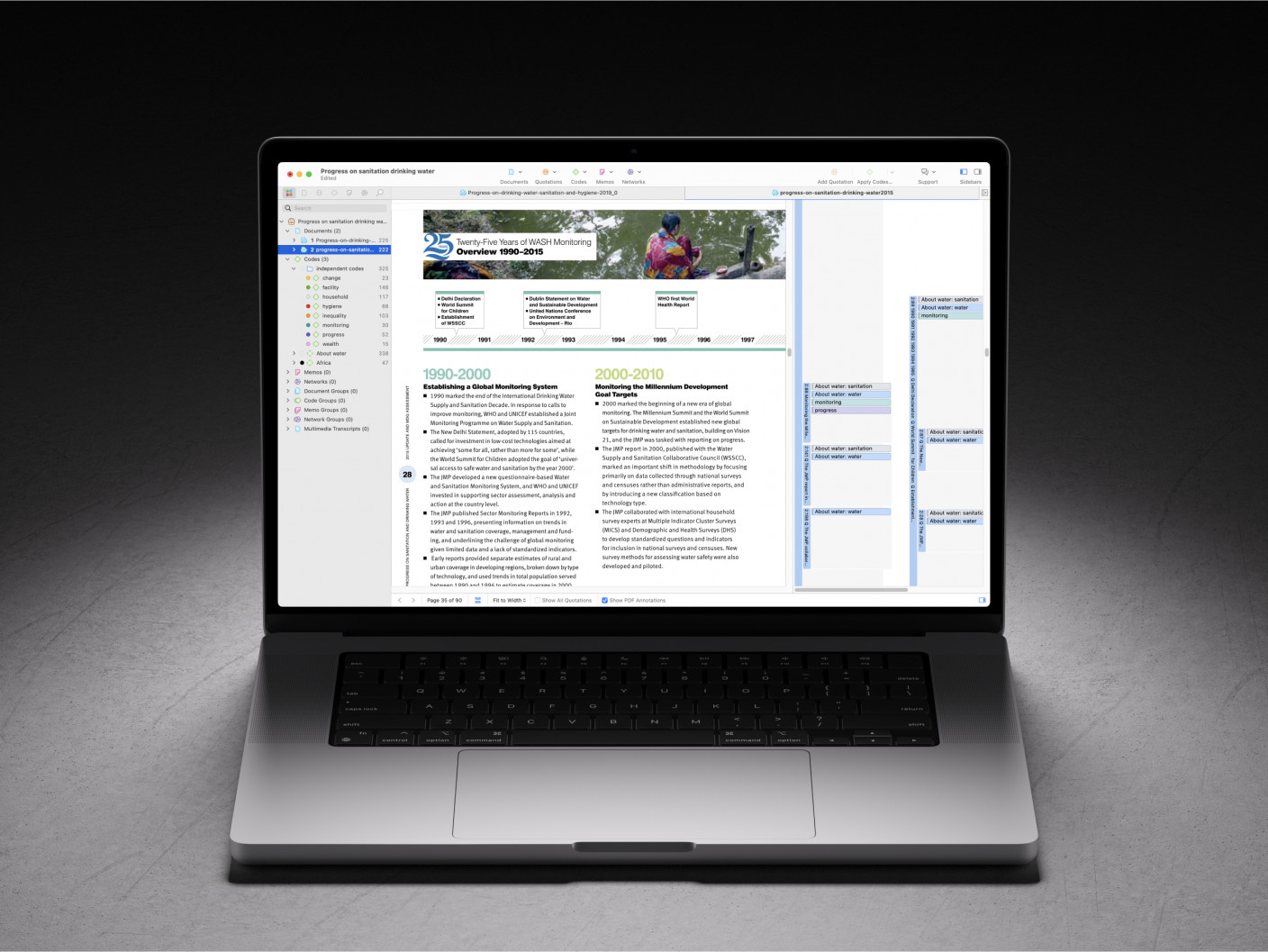

Collecting and analyzing data

Once the objectives are set and the participants are chosen, the next step is data collection. Employ the same tools, methods, or interventions you plan to use in the research. Finally, analyze what you have collected with a keen eye for patterns, anomalies, or unexpected outcomes.

This phase isn't just about collecting preliminary insights for the main study but about gauging the effectiveness of your methods and drawing insights to refine your approach.

Steps after evaluation of pilot testing

Reflections on the design of your study should follow pilot testing. The final design that you decide on should be informed by any useful insight you gather from your pilot study.

Adjust study methods

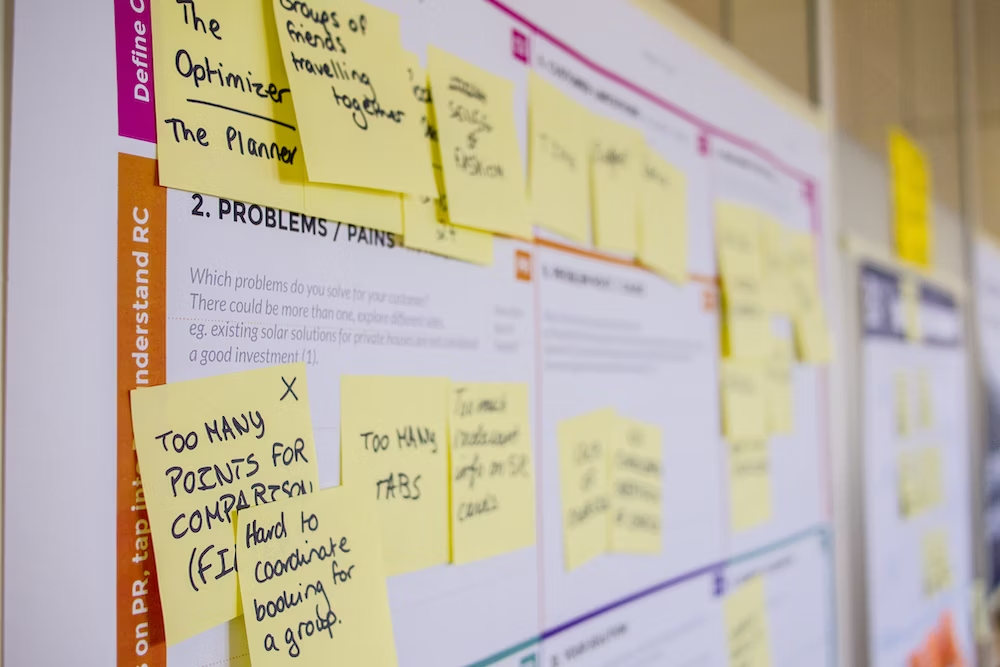

Pilot studies are especially useful when they help identify design issues. You can adjust aspects of your study if you found they did not prove effective in collecting insights during your pilot study.

Identify opportunities for richer collection

Pilot testing is not merely a phase to iron out mistakes and shortcomings. A good pilot study should also allow you to identify aspects of your study that were successful and would be even more successful if fully optimized. If there are interview questions that resonated with research participants, for example, think about how those questions can be better utilized in a full-scale study.