Research Methods in Social Sciences | Practices, Examples & Tips

- Introduction

- What are the social sciences?

- What research methods are used in the social sciences?

- Further reading

Introduction

Conducting a research project in the social sciences has some different considerations to conducting research in the physical, natural, or materials sciences. Data collected from human subjects can come from various methods that include but also extend beyond experiments and other controlled inquiries more often found in research in physics, engineering, or biology.

This article explores central research methods that are employed to develop new theories in the social sciences.

What are the social sciences?

Any field that has to do with cultures, interpersonal interactions, or any social aspect of the human experience falls under the umbrella of the social sciences. These fields contrast with sciences such as chemistry and geology.

The main consideration for social science research is the complexity of dynamics between people. The individual differences that define identity, language, culture, power, and other social dynamics ultimately confound the search for universal theories more commonly sought by other researchers in the "hard" sciences.

As a result, social science researchers, at least those who are concerned with the nearly infinite complexities of cultures and communities, are more interested in pursuing theories that are transferable between contexts than theories that are generalizable. The nuance between these two qualities lies in the intent of explaining phenomena in a universally understood manner (e.g., "objects in motion stay in motion unless acted upon by an external force") or in a language that can be adapted across contexts (e.g., "our understanding of this particular workplace should be compared to our understanding of this other workplace").

The social sciences accommodate various forms of non-experimental research, such as ethnographic research, action research, and life history research. These naturalistic methods aim to capture data as they occur in their natural environment rather than in a set of controlled conditions that may not reflect the realities of the social world.

Note that this does not preclude social science researchers from pursuing experimental research. Indeed, there are many social science inquiries that can benefit from the traditional control group/experimental group dynamic, particularly in education, psychology, and marketing. However, the acknowledgment of the ever-changing nature of the social world opens researchers to a wider variety of methods that may not be appropriate in the physical and material sciences.

What research methods are used in the social sciences?

There are many different methods used in social science research, and the most appropriate methods for any particular topic depend on the research question being explored.

One key principle that governs a researcher's choice of methods is that what people say, do, and believe can be entirely different things altogether. The idea of social desirability bias, for example, casts doubt on interview or survey responses that too easily conform to societal norms (e.g., "I don't drink alcohol" or "I often donate to charity"), making observation research methods more appropriate to really understand behaviors and actions.

That said, what people state in interviews or questionnaires can prove valuable to fields such as linguistics, sociology, and communication. How research participants word their beliefs and interact with researchers or with each other can provide useful insights on any number of research inquiries.

While the social sciences relies heavily on qualitative research, quantitative data may also be collected for quantitative and mixed-methods analysis. The decision to choose a particular research paradigm depends on whether the researcher wants to explore participants' perspectives, in which case qualitative research is more appropriate, or to measure broader trends, justifying quantitative research. On the other hand, more ambitious research designs may look to a mixed-methods approach to capture a phenomenon in a more comprehensive manner.

Interviews

Conducting interviews is one of the core tasks of social science researchers who want to grasp the opinions and perspectives of research participants. Interviews are designed interactions with research participants in order to gather answers that can address the main questions of a study.

While it is one of the more common research methods in the social sciences, it is also one of the most complex. The quality of interview data will depend on a number of factors, including the respondent's understanding of the interviewer's questions, the level of rapport between the interviewer and their respondents, and the extent to which the topics explored are of a sensitive nature. The richness of the data allows researchers to analyze both the meaning conveyed by research participants as well as the nature of how that meaning is expressed and understood.

Interviews can be structured, unstructured, or semi-structured depending on the sort of interaction the researcher wants to pursue for data collection. Structured interviews allow for an ordered collection of data through a predetermined set of questions, while unstructured interviews give the interviewer the freedom to pursue lines of research inquiry wherever they might go with their respondents. Meanwhile, semi-structured interviews will rely on a set of questions beforehand but will also allow researchers to follow up on the answers to those questions if the potential for exploring other avenues presents itself during the course of an interview.

Interviews can be analyzed in a number of ways, such as thematic analysis, where the goal is to identify the prevailing patterns in respondents' perspectives, or content analysis, where researchers identify what words or phrases are most often used by respondents.

Focus groups

At first glance, a focus group looks very similar to an interview, except that that the researcher elicits opinions from multiple participants, rather than a single respondent, in one setting. However, the dynamics of focus group research accommodate research inquiries related to social interactions or collective meaning-making.

Researchers who opt for focus groups over interviews might plan for activities other than straightforward question-and-answer exchanges. Such activites might include group presentations, role plays, and debates to explore and collect data on different kinds of engagements among research participants.

The variety of interactions that can be observed and analyzed through focus group research highlights the different ways that opinions and perspectives can be expressed. More importantly, it emphasizes the variety of research inquiries that are possible by looking at both the substance of issues discussed in focus groups as well as the discursive strategies employed by research participants during interactions with each other.

Observations

When researchers want to understand the behaviors, actions, and other dynamics within a particular research setting, they can simply go into the field and observe it. Observation research methods are appropriate for field research to collect naturalistic data that otherwise couldn't be collected in controlled experiments under artificial conditions.

The data from observational research often takes the form of field notes that, when collected in a consistent and organized manner, provide a detailed description of events as they happened and were observed in the field. Field notes that provide thick description can explain complex cultural phenomena such as religious observances, rituals, and interpersonal interactions.

Observational research can also include images, videos, and audio recordings. This sort of data can help the researcher recall events they experienced or observed and provide a rich level of detail that words alone may not be able to convey to the research audience.

Research in communication science, for example, may examine how facial expressions, gestures, and other body language inform how meaning is conveyed and interpreted between speakers. Anthropology can also benefit from multimedia data collection providing visual or aural insights on cultural artefacts rarely experienced or analyzed.

Ethnography and case study research often include observations as a means to supplement interview or survey data collection. Through the concept of triangulation, researchers can analyze observational data and data that captures research participants' perspectives and utterances to synthesize a deeper understanding of social phenomena.

Surveys

Questionnaires or surveys allow for data collection on a large scale by eliciting the opinions of multiple participants through a fixed or standardized set of questions. They are designed to make the data collection process as systematic as possible while providing a structured set of data that is more straightforward to analyze compared to field notes or transcripts.

Surveys can include quantitative and qualitative questions, depending on the research question being addressed. A survey data set can be broken down into multiple subsets based on survey responses to questions such as gender, age, ethnicity, income level, education, or other questions which have a closed or limited set of answers for respondents to choose from.

For example, a survey on education might want to make assertions about the relationship between university student performance and the amount of energy drinks consumed. The researchers could then write question items asking about students' grades, their level of satisfaction with their own academic performance, and their purchases of various energy drinks. The data from these answers can provide the basis for a statistical analysis that can show any potential connections that might be pursued through further research.

The qualitatitve component of surveys often involves how people respond to open-ended questions. Surveys could include questions such as "List the words you would use to describe this product" or "In what ways has this class contributed to your understanding of the subject?" These sorts of questions invite various responses which oftentimes cannot be predicted at the outset of the study.

Open-ended responses from surveys can be analyzed with methods such as thematic analysis or content analysis in order to identify what common words, phrases, or perspectives were commonly expressed by respondents.

The standardized nature of surveys makes data collection easy, but the main drawback is its limitation in gathering rich data on deeper individual perspectives. Oftentimes, survey respondents are hesitant to take more than 5-10 minutes to complete a survey, and they are likely to feel discouraged by answering too many open-ended survey questions at length.

As a result, researchers will more often turn to interviews or narratives to capture deeper insights than what are commonly found in survey research. However, survey data can provide some useful knowledge about patterns and trends within a particular population, especially if little is known to begin with.

Researchers will often employ survey research methods as a preliminary step to uncovering previously unknown trends in respondents' behaviors and opinions. This information can prove essential to designing questions for follow-up interviews or refining the analytical lens for observations.

Secondary data

A significant portion of research depends on primary data collection through the methods described above. However, secondary data also plays an integral role in the development of knowledge in the social sciences.

Secondary data refers to any information that already exists or was previously collected by other researchers. For example, charts and tables reporting statistics are products of primary research. These visualizations, when taken in the aggregate, can form the basis of a secondary research study that looks at multiple sources of data at the same time.

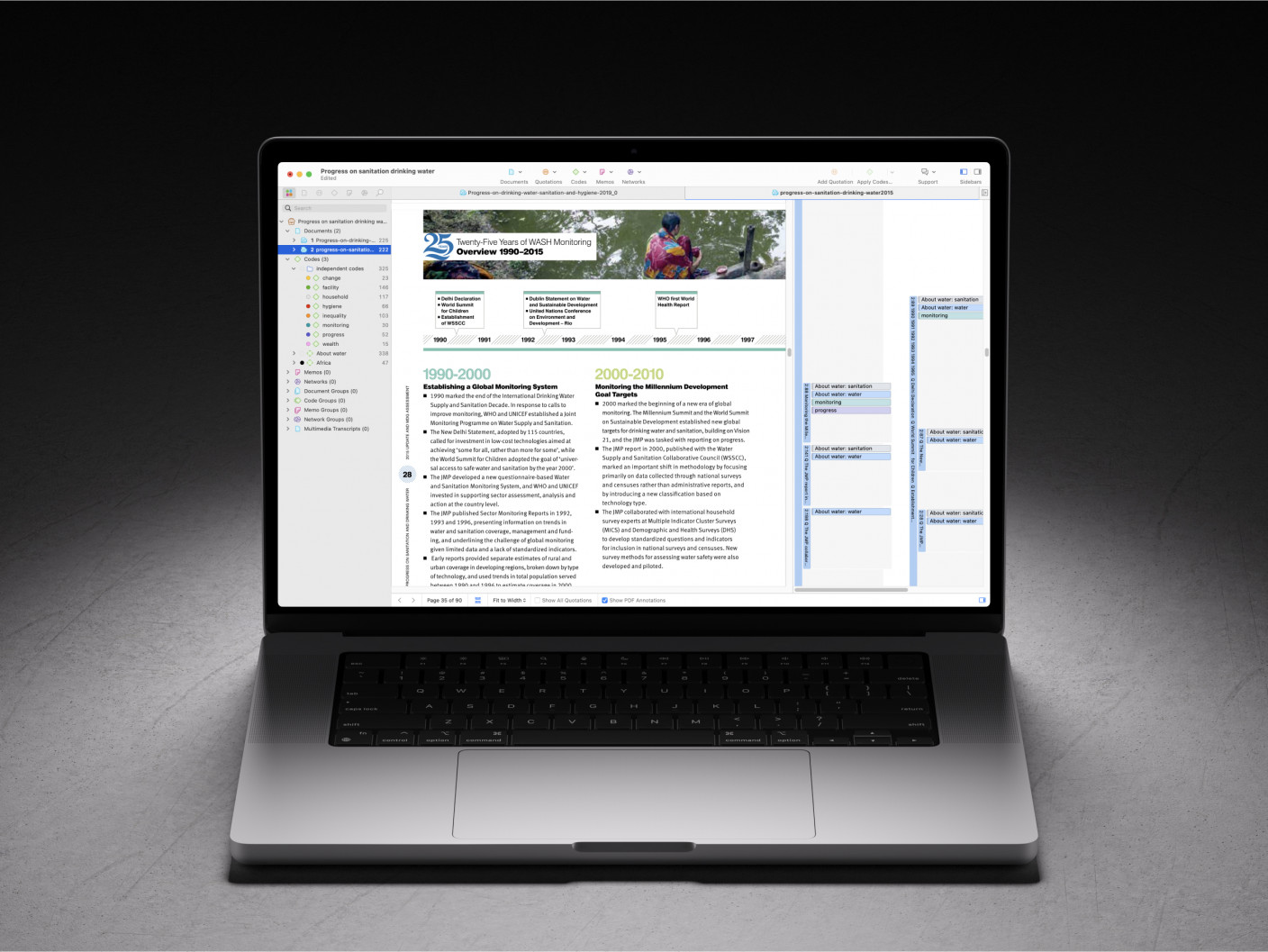

Archival research relies on a combination of primary data such as historical records and official documents and secondary data such as existing analysis of that data. This synthesized analysis gives researchers a second look at data that has already been researched but may benefit from a fresh perspective to yield new insights.

A literature review is also a form of secondary data collection, as the goal of a literature review is to synthesize existing research for the purpose of shedding light on a research problem or framing a new research question. Literature reviews are an essential component of any full research study, as it implies a comprehensive understanding of the current scientific knowledge relevant to the research inquiry.

Quantitative methods

Even though there is significant overlap between social science research and qualitative research, they are not interchangeable terms. Many fields, such as business, sociology, and linguistics, require some way to measure concepts or phenomena, most likely through statistics and frequency analysis.

Quantitative data can be drawn from any number of research methods and can refer to any information that can be countable. While the physical and material sciences measure aspects of phenomena such as temperature, wind speed, and weight, the social sciences might count things such as income level, retirement age, and hours spent working.

Even subjective or socially constructed concepts such as job satisfaction and political beliefs can be quantified to some extent. Likert scales in survey research, for example, prompt respondents to select a number on a scale that best represents their response to survey questions. The answers to Likert scale questions are then statistically analyzed for frequency and average.

Even the coding of qualitative data can be repackaged into quantitative data to identify the prevalence of recurring patterns in the social world. Many studies may count the frequencies of codes that are applied to interview transcripts or field notes to give a sense of what recurs in or what is missing from the data.

The drawback of quantifying data lies in the potential to lose the essence of the dynamics inherent to the social world. For example, an anthropologist might quantify the amount of time in religious observances that are allocated to prayers, sermons, chanting, and singing. Without any further contextualization of detail, researchers risk reducing quantifiable data to simplistic representations of social phenomena.

Mixed methods

Some research inquiries are better suited to a mixed-methods approach, which combines qualitative and quantitative research methods to address a topic from multiple angles and synthesize the resulting knowledge in a meaningful way.

Mixed-methods research is an intentional approach to exploring the social world through descriptive and confirmatory research methods. The use of multiple methods can be concurrent - in which case qualitative and quantitative research are conducted at the same time - or sequential - where qualitative research findings inform quantitative research, or vice versa. The kind of mixed-methods research design that is most appropriate depends on the particular needs of the research study.

Further reading

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2017). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Denzin, N. K. (2017). The research act: A theoretical introduction to sociological methods. Routledge.