Thick Description in Qualitative Research | Definition & Techniques

- Introduction

- What is thick description?

- What is an example of thick description?

- Key principles of thick description

- Creating and presenting thick descriptions in research findings

- Further reading

Introduction

Thick description is a concept in qualitative inquiry where cultures, communities, and interpersonal relationships are described in extensive detail to provide the research audience with an immersive understanding of the social world. Qualitative research methods such as ethnography and narrative research rely on thick description as it is a fundamental requirement for cultural analysis in scholarly research. The extensive level of detail facilitates a deep exploration of human behavior, interpersonal relationships, and cultural and social phenomena necessary to contribute to scientific knowledge. This article looks at the concept of thick description in depth and explains the aspects of thick description necessary for qualitative researchers to conduct rigorous qualitative research on cultural and social phenomena.

What is thick description?

Traditional scientific inquiry employs generalizability to extrapolate knowledge gained from research in one context to other contexts. Newton's first law of motion (an object's motion will remain constant unless the object is influenced by an external force) is generally assumed to be true unless contrary evidence is identified and presented (discussion of the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle provides pathways for such exceptions). As more data and analysis are incorporated into scientific knowledge, the laws of motion and, of course, all other scientific theories and frameworks, undergo development with the intent of forming a perfect or universal understanding.

This search for all-encompassing theories that explain as much of our observable world as possible creates the impression that everything can be reduced to simple explanations that are universally applicable regardless of context or conditions. Under sociocultural paradigms to research, this is a challenging proposition to accept given the complex nature of social relationships, cultural norms, and power dynamics. Rather than rely on a theoretical framework from one context to explain others, qualitative researchers who employ ethnography, narrative research, life history research, and other rich methods aim for thick description to give the research audience a full understanding of cultures and communities that they want to show through research.

Gilbert Ryle (1968) is the first major scholar to define thick description in contrast with superficial descriptions that lack sufficient context. A thin description is shallow in nature, providing little context or background information to the extent that the resulting representations of cultures or communities under observation lack authenticity and real voices. Clifford Geertz further formalized the definition of thick description with his essay "Thick description: Toward an interpretive theory of culture" (1973). Most importantly, the cultural and social relationships under study are identified and contextualized within their larger environment, with all of these details made clear to the research audience. Later on, Norman K. Denzin in his book The Research Act (2009) references Geertz in describing thick description as an approach that allows researchers to capture the intricate dimensions of cultural and personal experiences.

What is an example of thick description?

First, let's talk about what a thin description would look like:

"I participated in a traditional tea ceremony at a Japanese temple."

If this were part of a study aimed at helping the research audience explore the Japanese context, this description alone would be severely lacking. Those who are unfamiliar with Japanese culture are bound to read such a superficial account and have a multitude of questions:

- Why does tea require a ceremony?

- What is the importance of having a tea ceremony at a temple?

- What makes this tea ceremony Japanese?

Absent answers that the researcher should provide, the research audience is left to either apply their own assumptions about the context (which can foster stereotypes and misconceptions) or treat the research as unpersuasive. Neither path benefits the development of scientific knowledge of the social world.

A thick description could look like this:

"Chakai, tea gatherings, are another context in which ceremonies are performed. A tea organisation may rent out the grounds of a temple or a restaurant and hold a day of ceremonies. A schedule is published, with several different ceremonies taking place simultaneously. Participants - usually members of the organisation - may attend the rites of their choice. The hosts are all selected in advance, sometimes performing publicly in order to demonstrate the attainment of a high rank. A recital or a concert would be a close analogue. I have also participated in tea ceremonies held as part of some festival or celebration. For example, during a 'Cultural Festival', my teacher's students were asked to prepare and serve tea for any passersby who might want to act as guests. First and foremost, however, the tea ceremony is a highly ritualised version of the host/guest interaction, and a heightened expression of the emphasis on etiquette in Japanese culture in general. It embodies the appreciation of formalised social interaction and the importance, for example, of learning tatemae, the graces necessary to maintain harmonious social interaction. The theory is that mere good intentions are insufficient; one must know the proper form in order to express one's feelings of hospitality effectively." (Kondo, 1985, p. 288)

A more detailed account allows the research audience to immerse themselves in the sensory and contextual knowledge that they may not otherwise be familiar with in their own context. With this depth of information, the researcher and their audience have greater insights as to how theoretical insights may differ across environments.

This is not to say that thin description doesn't serve a purpose in scholarly research. Surveys and experiments in quantitative studies are limited in the level of detail they provide in contrast with ethnographic observations or extensive interviews. Thin description is thus more of a circumstance in confirmatory research or research that employs quantitative methods where concepts are measured rather than explored. In contrast, even the most basic concepts in the social sciences, such as cultural practices, cultural and social relationships, and interpersonal interactions, benefit from thick description when the research audience needs a deep level of context to understand and analyze the data presented to them.

Key principles of thick description

Qualitative data that provides detailed descriptions of social phenomena exhibit five key characteristics that bolster the rigor of the data collection and analysis. Let's look at each of these qualities below.

Contextualization

One of the most useful characteristics a qualitative researcher can use to explain the actions and behaviors of research participants is context. Ethnographic research is a core component in the interpretation of cultures and invariably requires rituals and social interactions to be situated in its broader context to establish the rationale of organized practices, social norms, and other related phenomena.

Level of detail

Detailed accounts of social phenomena provide as much nuance as possible to allow the research audience to almost feel as if they could experience the research context simply by reading about it. Sensory information, contextual knowledge, and insider insights all contribute to the necessary depth expected from a thick description.

Interpretation

Thick description is not simply an abundance of information about a particular context. Especially in ethnography, researchers are expected to gather data from research participants themselves regarding their roles within the context and the epistemologies that inform their behaviors. Interviews and focus groups supplement data regarding observed developments with the viewpoints of insiders and other involved participants.

Perspective

The other part of the subjective nature of the interpretation of cultures involves the perspective of the researchers themselves, who must also acknowledge their own view of the world. Establishing the points of view from both the researcher and the researched provides both guidance on how theories are interpreted and applied to the data and an example for the research audience in how they could look at the context and its participants.

Reflexivity

Thick description requires the researcher's critical reflections of where they stand in relation to their research participants, taking into account any preconceptions that might affect the interpretation and analysis of the data. Above all, there is an acknowledgment that there is no one right or objective way of looking at the research context, and that inquiry about the social world can yield multiple interpretations. A full awareness and explanation of one's positionality relative to the research participants is essential for the research audience to understand how to situate the research.

Creating and presenting thick descriptions in research findings

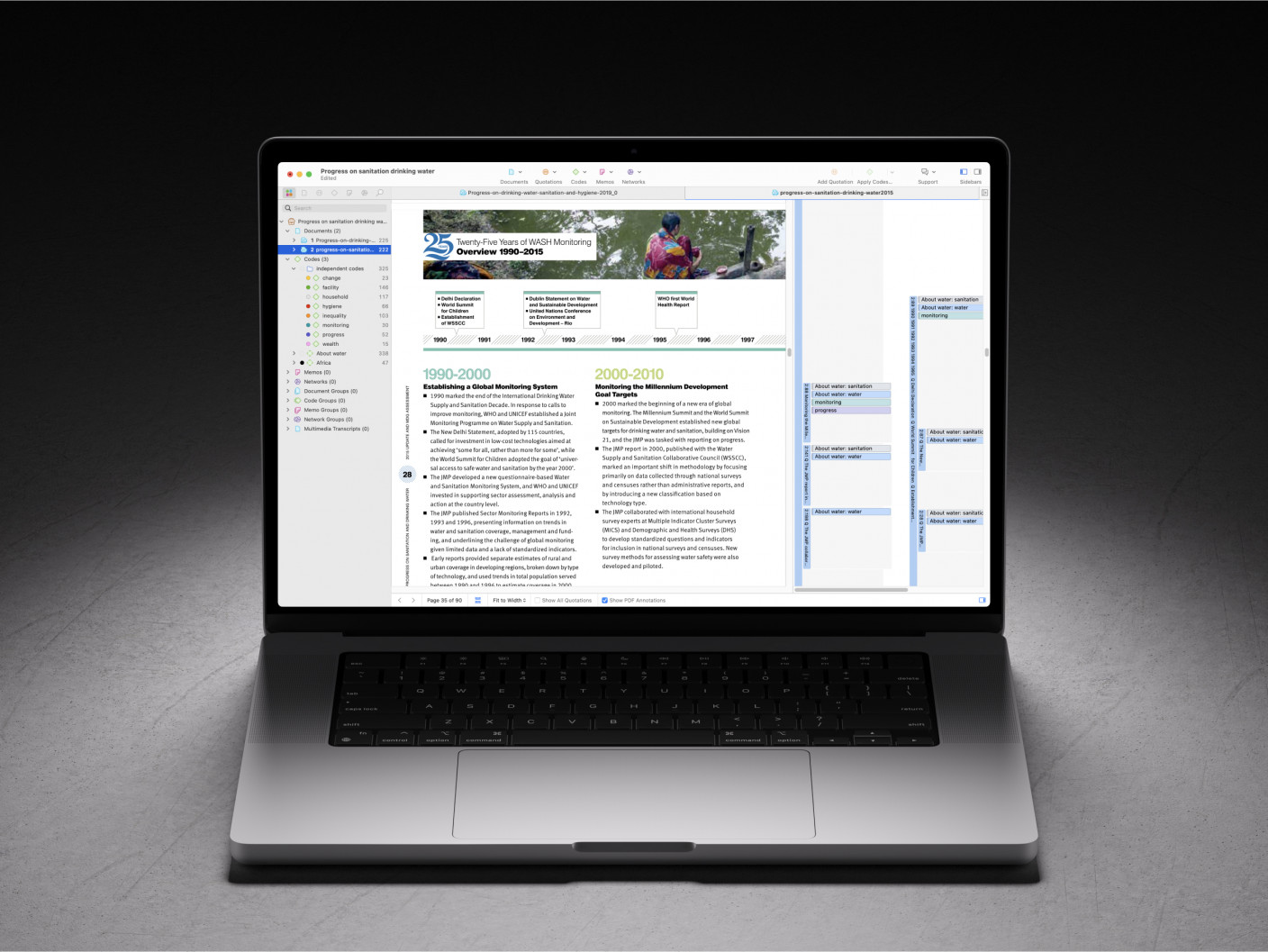

Thick description is best generated from rich qualitative data. A rigorous researcher employs field data, interview transcripts, collected artifacts, photos or videos of phenomena, and any other data that can satisfy the principles listed above. In most cases, more comprehensive research methods such as ethnography and narrative research are best suited for explaining culture, community, and other social concepts through thick description.

Field experiences make up the bulk of data that documents the actions and behaviors of the observed. Through observations, the researcher makes explicit, detailed accounts of cultural practices and social interactions in their own words in field notes and the resulting interpretations drawn from those notes. With a research question, a theoretical framework, or both to guide their observational lens, researchers take notes on their objects of inquiry and the peripheral knowledge necessary to understand what is being observed.

For thick description, observational data should be supplemented by perspectival data that often comes from interviews and focus groups. These methods capture an insider perspective on actions and behaviors that are observed. The resulting data often comes in the form of transcripts so that opinions can be thoroughly documented and disseminated, but audio or video data can also be analyzed to capture how research participants talk about their own behaviors, which can also provide valuable insight about the context under study.

Taking all of these into consideration, a qualitative report that provides thick description should provide as much detail as possible about the research context and the phenomena that the researcher observes in that context. Surface appearances should be avoided above all; nuances that are potentially unfamiliar to the research audience and are useful to describing the context and addressing the relevant research questions should be documented in any papers or presentations that disseminate the research.

Further reading

- Denzin, N. K. (2009). The research act: A theoretical introduction to sociological methods. London: Routledge.

- Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures: Selected essays. New York: Basic Books.

- Kondo, D. (1985). The way of tea: A symbolic analysis. Man, 20(2), 287-306.

- Ryle, G. (1968). Thinking and reflecting. Royal Institute of Philosophy Lectures, 1, 210–226.