- What is Interview Analysis?

- Advantages of Interviews in Research

- Disadvantages of Interviews in Research

- Ethical Considerations in Interviews

- Preparing a Research Interview

- Recruitment & Sampling for Research Interviews

- Interview Design

- How to Formulate Interview Questions

- Rapport in Interviews

- Social Desirability Bias

- Interviewer Effect

- Types of Research Interviews

- Face-to-Face Interviews

- Focus Group Interviews

- Email Interviews

- Telephone Interviews

- Stimulated Recall Interviews

- Interviews vs. Surveys

- Interviews vs Questionnaires

- Interviews and Interrogations

- How to Transcribe Interviews?

- Verbatim Transcription

- Clean Interview Transcriptions

- Manual Interview Transcription

- Automated Interview Transcription

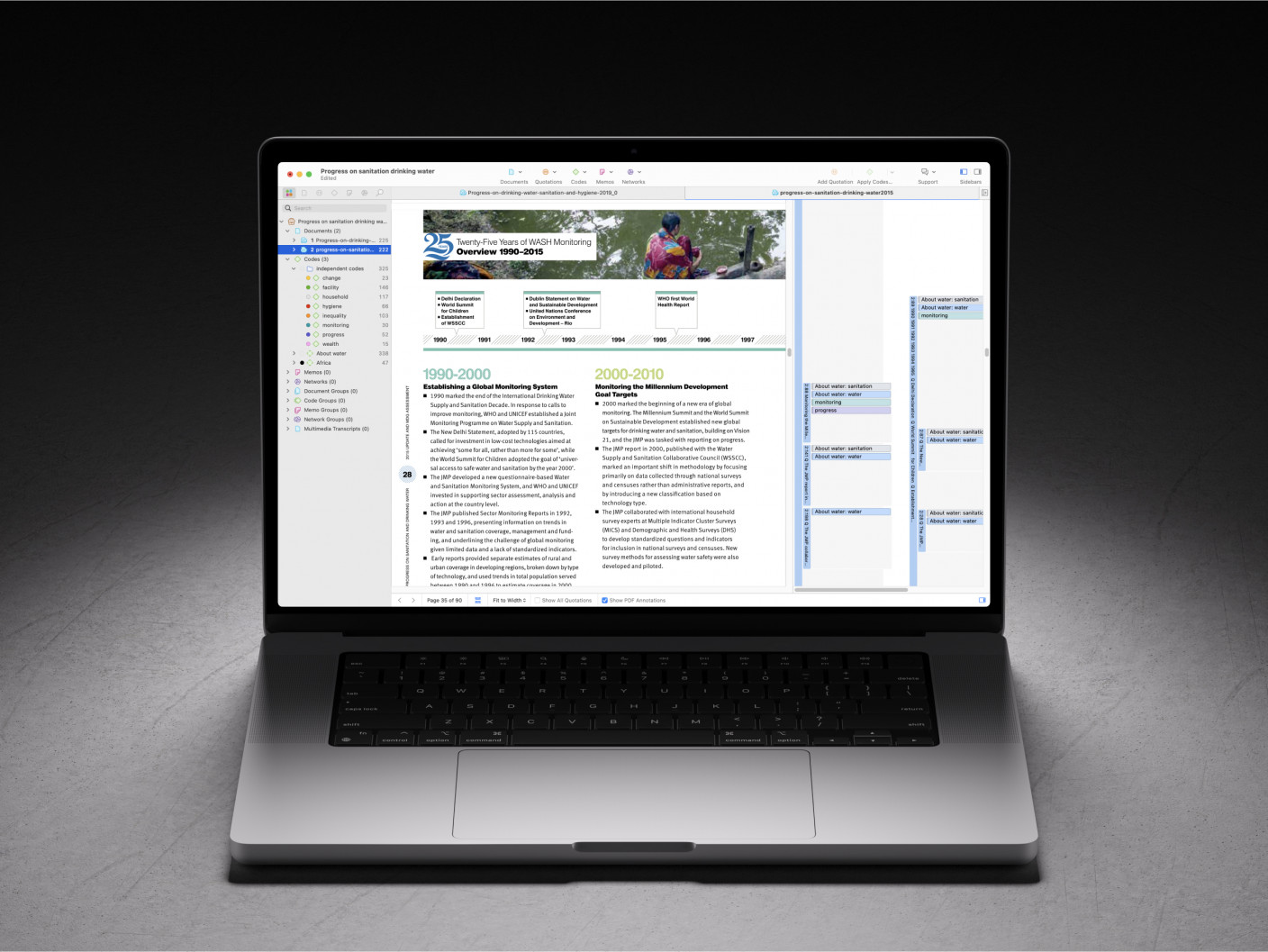

- How to Annotate Research Interviews?

- Formatting and Anonymizing Interviews

- Analyzing Interviews

- Coding Interviews

- Reporting & Presenting Interview Findings

Rapport in Interviews

Rapport building is the process of connecting with a person and establishing confidence. It provides a safe and comfortable space to communicate. Strong communication and connection with the participant are essential for information collection when conducting interviews. In this article, we will cover the basics of rapport building, ethical considerations, and provide advice on how to build rapport with participants in qualitative research.

Introduction

The word rapport originates from the French term "rapporteur" which means "to bring back" or "to relate." It stems from the Latin root re- (again) and portare (to carry). Initially, the term described the act of returning or reporting something, but over time, it evolved to refer to a relationship characterized by mutual understanding and harmony. Today, "rapport" is widely used to describe positive interactions where trust and attentiveness foster a productive exchange between individuals, particularly in contexts like interviews.

Rapport building in interviews involves creating a relationship based on mutual respect, attentiveness, and trust. It goes beyond asking questions and collecting responses—it requires showing genuine interest and engaging in meaningful conversation. Body language, such as maintaining eye contact, mirroring body language, and using nonverbal cues, plays an essential role in establishing rapport. These nonverbal correlates communicate attentiveness and help to build a positive connection, making the interviewee feel more comfortable and valued.

In addition to nonverbal communication, verbal techniques like active listening, positive reinforcement, and relevant follow-up questions are key to rapport building. Listening actively means not only hearing what the interviewee is saying but also acknowledging their responses through gestures or brief verbal affirmations. Engaging the interviewee in a way that shows you are fully present and interested in their answers builds trust and encourages a more open conversation.

Why is rapport important?

Rapport is an essential element of the interview process because it directly influences the quality and depth of the information collected. Participants may feel distant, guarded, or unwilling to share their true thoughts or experiences without rapport. This can lead to incomplete or superficial answers, which limits the effectiveness of the interview and hinders the research findings.

Building rapport varies depending on the method of the interview. In focus groups, rapport building doesn't play as important a role as in individual face-to-face interviews, but it is still important to build confidence and respect for participants.

When participants connect with the interviewer, they are more likely to express their true feelings and opinions. This openness leads to richer data and a deeper understanding of the subject matter. Rapport helps to establish trust between the interviewer and the participant. Trust is crucial in ensuring that participants feel comfortable sharing sensitive or personal information, which can be particularly important in research settings involving emotional or controversial topics.

Good rapport facilitates smoother communication. Participants are more likely to elaborate on their responses and engage in meaningful dialogue when they feel that the interviewer is genuinely interested and paying attention to their answers. Many participants may feel nervous or uncertain during interviews, especially if the topics are unfamiliar or personal. Rapport building helps to alleviate these anxieties by creating a relaxed and supportive environment that stimulates engaging conversation.

In short, rapport is crucial for gathering detailed and authentic data. It transforms the interview from a mere question-and-answer session into a more natural and productive conversation, allowing for better insights and understanding.

Rapport can positively and negatively influence data quality (Horsfall et al., 2021). High levels of rapport reduce missing responses, as respondents are more motivated to complete the interview. However, it may lead to socially desirable answers, especially on sensitive topics, as respondents may avoid discomfort or offending the interviewer. In the study by Horsfall et al., researchers found that rapport decreased missing responses by 20% but encouraged socially desirable responses in questions about income or legal matters. However, they also found that rapport did not significantly affect consistency in self-reported alcohol consumption compared to face-to-face interviews, suggesting that memory might play a greater role in consistency. Although rapport generally improves cooperation, it complicates the accuracy of responses in sensitive contexts.

Key elements for building rapport

Human communication is complex and rapport is a diverse equation of verbal and nonverbal communication and genuine interest from everyone involved. While there is no specific formula for building rapport during an interview, there are some suggestions that researchers can follow to build rapport:

Active listening

Active listening is one of the most effective ways to build rapport. This means giving your full attention to the participant, responding appropriately, and acknowledging their answers with verbal cues. Active listening shows that you are engaged and interested in what the participant is saying, which encourages them to open up more. Just recording the participant and not engaging in the conversation may reduce the quality of the information shared.

Maintain eye contact

Eye contact is a powerful tactic for establishing connection and trust. By maintaining eye contact, you signal to the participant that you are present and focused on them. However, it is important to strike a balance—too much eye contact can be intimidating, while too little can make you seem disinterested.

Use positive reinforcement

Encouraging participants with positive reinforcement, such as nodding or offering brief affirmations, helps to create a supportive and respectful environment. This shows that you value their input and are interested in their perspectives.

Ask open-ended questions

Open-ended questions are essential for encouraging participants to share detailed and thoughtful responses. These types of questions invite participants to reflect on their experiences and opinions, providing richer data. For example, instead of asking “Did you like the event?” you might ask “What were your thoughts on the event?”

Mirroring body language

Subtle mirroring of the participant’s body language can help to establish rapport by creating a sense of synchrony and mutual attentiveness. For example, if the participant leans forward during the conversation, you might do the same. However, this technique should be used naturally and not forced, as participants may pick up on disingenuous behaviour.

Show genuine interest

Building rapport requires that the interviewer demonstrate a genuine interest in the participant’s responses. This can be done through thoughtful follow-up questions, asking for clarification on certain points, or showing enthusiasm for the topics being discussed. When participants feel that the interviewer is genuinely interested, they are more likely to engage fully in the conversation.

Be respectful and empathetic

Respect and empathy are key components of rapport building. Showing respect for the participant’s opinions and experiences, even if they differ from your own, helps to create a safe and supportive environment. Empathy, or the ability to understand and share the feelings of others, allows the interviewer to connect on a deeper level with the participant.

Comfortable atmosphere

During the interview, showing interest is pivotal along with creating a comfortable environment that provides a safe space for the participants to share information. When it comes to face-to face interviews, it is ideal to find a location with minimal distractions and interruptions, provide water if needed, a comfortable seat, and a location that is convenient.

Ethical challenges of building rapport

Qualitative researchers frequently encounter ethical tensions when building rapport with vulnerable participants in interviews. A recent study by Schmid, Garrels, and Skåland (2024) identified key challenges: the need for extra rapport-building efforts, the risk of disclosing more than intended, and the struggle to maintain professional boundaries while balancing emotional support. Too little rapport can hinder data collection, while over-rapport may lead participants to overshare, risking emotional harm or regret. Researchers must find a balance to protect both themselves and participants. Training programs should emphasize these ethical tensions to ensure researchers can navigate rapport carefully in sensitive settings.

One key tension is ensuring that rapport-building efforts do not blur the lines between researcher and participant. While building trust and empathy is essential to gather rich, detailed data, researchers must also maintain professional boundaries to avoid emotional entanglement. Researchers often feel compelled to offer additional support, particularly when participants disclose highly sensitive or traumatic information, creating a moral dilemma over their responsibility toward the participant's well-being. Some researchers also experience over-rapport, where participants confide beyond the study's scope or later regret sharing personal information, complicating the researcher's role.

Another challenge arises when rapport influences the flow of information in interviews. Participants who trust the researcher may disclose more personal details, some irrelevant to the study, placing researchers in ethically complex situations. Vulnerable participants may also share distressing or traumatic experiences that researchers must navigate without causing harm. Determining when to push forward with sensitive questions or when to hold back is a critical skill that researchers must develop to balance data collection and the participant’s emotional health.

In addressing these tensions, qualitative researchers need to be conscious of the continuum of rapport, avoiding both under and over-rapport. Too little rapport results in distant, shallow interviews, while too much can result in emotional strain for both parties. Academic programs and research institutions should incorporate discussions about these ethical challenges, encouraging researchers to approach rapport-building with greater care and ethical awareness (Schmid, Garrels, & Skåland, 2024). This can prevent the negative effects of over-rapport, such as re-traumatization, and reduce the chances of participants withdrawing their consent after interviews.

Ultimately, the study by Schmid, Garrels, and Skåland (2024) calls for a more nuanced and reflective approach to rapport-building, urging qualitative researchers to be attentive to the balance between establishing trust and respecting boundaries. By fostering a clear understanding of the ethical implications of rapport in interviews with vulnerable populations, researchers can collect richer data while safeguarding the well-being of their participants.

Conclusion

Rapport building in interviews is a vital process that creates a space where participants feel safe, valued, and willing to share personal or sensitive information. Through a combination of active listening, eye contact, non-verbal cues, and positive reinforcement, interviewers foster trust and attentiveness, encouraging more open communication. Strong rapport leads to richer, more detailed data by helping participants feel comfortable discussing topics they may otherwise withhold.

In interviews, researchers are advised to maintain a balance between showing genuine interest and preserving professional boundaries. Active listening involves engaging fully in the conversation, offering affirmations, and asking open-ended questions that prompt deeper reflection. Using non-verbal cues, such as mirroring body language, enhances connection and builds a sense of synchrony between the interviewer and interviewee.

Researchers must be careful not to push participants too far or invade their comfort zones while still striving to gather valuable data. Ethical concerns arise when rapport is taken too far, where participants may feel pressured to share personal details they later regret. In vulnerable populations, such as those dealing with trauma or sensitive personal issues, rapport must be managed with sensitivity to prevent re-traumatization or feelings of exploitation. The line between trust-building and professional distance must be carefully maintained to ensure that participants' well-being is prioritized, even as researchers seek detailed insights.

Overall, rapport building is essential for meaningful qualitative research but must be navigated with care, particularly in sensitive settings. Academic training and researcher preparation should emphasize the ethical dimensions of rapport, equipping researchers to foster trust without crossing personal boundaries. By carefully managing rapport, qualitative researchers can gather rich, authentic data while maintaining the ethical integrity of their research process and protecting the emotional well-being of their participants.

References

- Horsfall, M., Eikelenboom, M., Draisma, S., & Smit, J. H. (2021). The Effect of Rapport on Data Quality in Face-to-Face Interviews: Beneficial or Detrimental?. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(20), 10858. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182010858

- Schmid, E., Garrels, V., & Skåland, B. (2024). The continuum of rapport: Ethical tensions in qualitative interviews with vulnerable participants. Qualitative Research, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/14687941231224600