- What is Interview Analysis?

- Advantages of Interviews in Research

- Disadvantages of Interviews in Research

- Ethical Considerations in Interviews

- Preparing a Research Interview

- Recruitment & Sampling for Research Interviews

- Interview Design

- How to Formulate Interview Questions

- Rapport in Interviews

- Social Desirability Bias

- Interviewer Effect

- Types of Research Interviews

- Face-to-Face Interviews

- Focus Group Interviews

- Email Interviews

- Telephone Interviews

- Stimulated Recall Interviews

- Interviews vs. Surveys

- Interviews vs Questionnaires

- Interviews and Interrogations

- How to Transcribe Interviews?

- Verbatim Transcription

- Clean Interview Transcriptions

- Manual Interview Transcription

- Automated Interview Transcription

- How to Annotate Research Interviews?

- Formatting and Anonymizing Interviews

- Analyzing Interviews

- Coding Interviews

- Reporting & Presenting Interview Findings

Analyzing interviews

Without the interview analysis process, qualitative research is impossible. Interviews are the most common data collection method that qualitative researchers use. This article focuses on different methods of analyzing qualitative data from interviews.

Introduction

Analyzing interviews in qualitative research unlocks a unique perspective, thought, or emotion. Interviews provide rich, in-depth data that offer researchers unparalleled insight into participants' lived experiences, opinions, and values. However, analyzing qualitative data effectively requires more than just listening; it demands a systematic approach to uncover the deeper meaning embedded in the words. The different methods of qualitative interview data analysis are key to transforming raw conversations into meaningful insights.

From identifying patterns through qualitative interviews to employing techniques for analyzing qualitative interview data, these methods help researchers break down complex information into manageable parts. The coding process is particularly vital, allowing researchers to tag and categorize data, transforming it into something that can be analyzed and interpreted. By coding qualitative data, researchers can identify themes and key data segments that reveal underlying trends and meanings. Additionally, the use of more modern approaches like sentiment analysis adds another layer to the interpretation, helping to gauge emotions and reactions embedded in responses.

Methods for interview analysis

In qualitative research, interview analysis methods are essential for uncovering the deeper meanings, patterns, and insights within participants' responses. From thematic analysis, which identifies common themes across interviews, to grounded theory, which builds new theories from the data, each method offers a unique approach. The choice of method depends on the research objectives, the nature of the data, and the type of insights the researcher aims to achieve. Interview analysis methods enable a structured yet flexible interpretation of qualitative data, providing valuable findings that contribute to the broader research landscape.

Thematic analysis

Thematic analysis is one of the most commonly used methods in qualitative research for identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns or themes within data. It allows researchers to distill data from interview transcripts or other qualitative sources to find commonalities and trends, offering rich interpretations. Braun and Clarke (2006) described thematic analysis as a flexible method that can be applied across a variety of research paradigms and is suitable for identifying themes that span across the dataset. The method is widely used because it provides a systematic way to capture patterns in participants' perspectives.

Familiarization with the data

The researcher first becomes deeply familiar with the data by repeatedly reading through the interview transcripts, listening to recordings, and taking initial notes. This phase is crucial for immersion in the dataset, allowing the researcher to start forming initial impressions and to understand the data context.

Generating initial codes

The researcher then systematically codes the data by assigning labels or short phrases to segments of text that capture significant or recurring ideas. Each code represents an important concept or observation, and this step helps to break the data down into manageable, categorized parts.

Searching for themes

Once the data has been coded, the researcher reviews the codes to find overarching themes or patterns. This involves grouping related codes together and identifying broader topics that are emerging across the data set. Themes go beyond the codes to capture larger patterns of meaning.

Reviewing and refining themes

At this stage, themes are checked against the coded data and the entire data set to ensure they are comprehensive and accurately represent the data. The researcher refines the themes, combining or breaking them apart as needed to best capture the key insights from the data.

Defining and naming themes

Once the themes are reviewed, they are defined and named to reflect the essence of the data they represent. The researcher writes detailed descriptions of each theme, explaining its relevance to the research question and supporting it with data excerpts.

Writing up the report

The final phase involves writing the report, which includes a detailed narrative explaining how the themes were identified, what they mean, and how they answer the research question. The write-up integrates direct quotes from participants and a synthesis of the thematic findings.

Narrative analysis

Narrative analysis is a method that focuses on the stories participants tell, and how those stories are structured to make sense of their experiences. Riessman (2008) emphasized that narrative analysis goes beyond the content of what is told to include how it is told and the contexts that shape these stories. This method is particularly useful for exploring personal or collective stories, identity formation, and meaning-making processes.

Transcription and structuring

The researcher first transcribes the interviews, paying close attention not just to what is said, but also to how it is said. The transcription process captures the narrative flow, and the researcher begins to identify key structural elements such as the beginning, middle, and end of the story, as well as turning points or critical events.

Thematic and functional analysis

After transcribing the data, the researcher analyzes the content of the stories for recurring themes or topics that are central to the participants’ narratives. The functional aspect of narrative analysis focuses on why the story is being told in a particular way and what function the narrative serves in the context of the participant's life or identity.

Comparative analysis

When analyzing multiple narratives, researchers look for similarities and differences in how participants construct their stories. By comparing narratives, the researcher can identify common experiences or perspectives that reveal broader patterns in the data.

Interpretation and storytelling

The final step involves interpreting the narratives, to provide insights about how participants make sense of their experiences. The researcher may highlight specific narrative strategies used by participants, such as how they justify or explain their actions, to provide deeper insights into their lived experiences.

Grounded theory

Grounded theory, as introduced by Glaser and Strauss (1967), involves building theory from the data itself, rather than testing existing theories. Charmaz (2006) later contributed a constructivist approach to grounded theory. Grounded theory is particularly valuable when there is no pre-existing theory to explain the phenomenon under study, or when the researcher aims to construct a new theory.

Open coding

In the open coding phase, the researcher breaks down the interview data into small, discrete parts and codes them based on the concepts or ideas present. This initial coding is highly detailed and serves to identify as many concepts as possible in the data.

Axial coding

After open coding, axial coding involves relating the codes identified during open coding to one another. This process organizes the codes into categories, identifying relationships between them to create a more structured understanding of the data. The goal is to find how the categories relate and what central themes are emerging.

Selective coding

Selective coding focuses on identifying the core category that integrates all the other categories. The researcher develops this core category into the central theme or theory of the study. Selective coding is essential for constructing a theory that explains the data comprehensively.

Theoretical sampling and saturation

As the theory emerges, the researcher collects more data to refine the theory, a process known as theoretical sampling. Data collection continues until theoretical saturation is reached, meaning no new themes or insights are emerging from the data, and the theory is fully developed.

Theory development

In the final stage, the researcher presents the theory that has been generated from the data. This theory is grounded in the data and provides an explanatory framework for the phenomenon under study, offering new insights or understanding.

Content analysis

Content analysis is a systematic method used to quantify and analyze the presence of particular words, phrases, themes, or concepts within textual data. Krippendorff (1980) defined content analysis as a replicable technique for making inferences from data to its context, allowing for the systematic examination of large amounts of qualitative data. This method is especially useful when researchers need to objectively measure the frequency of certain themes or patterns in the data.

Data preparation

The researcher begins by preparing the data for analysis, typically through transcription if working with interview data. This step involves organizing and cleaning the data to ensure consistency across the text.

Developing categories and coding frame

Next, the researcher develops a coding frame, a list of predefined categories or themes based on the research questions or theoretical framework. Each category is defined, and clear criteria are established for how segments of the data will be assigned to each category.

Coding the text

The researcher systematically applies the coding frame to the data, tagging segments of text that correspond to each category. Coding can be done manually or with the help of software, depending on the size of the dataset.

Quantifying and interpreting

In quantitative content analysis, the researcher counts the frequency of each code or theme to identify patterns and trends. These frequencies are then interpreted to draw conclusions about which themes are most prominent in the data, or how different themes relate to one another.

Drawing conclusions and reporting

The final step involves interpreting the coded data and presenting the findings in a report. The researcher discusses the significance of the most frequently occurring themes, making inferences based on the data patterns and their relevance to the research questions.

Discourse analysis

Discourse analysis examines how language is used to construct social realities and relationships. Fairclough (1992) emphasized that discourse is not just a reflection of social practices but also actively shapes them. Discourse analysis explores power relations, ideologies, and social contexts through the analysis of language, offering insight into how social structures and power dynamics are produced and maintained through communication.

Transcription and contextualization

The first step in discourse analysis involves transcribing interviews or conversations, with attention to both verbal and non-verbal communication. Researchers also consider the broader social or institutional context in which the discourse occurs, as this context plays a significant role in shaping language use.

Identifying discourses

Once transcribed, the researcher identifies specific discourses or ways of talking about the subject matter that are present in the text. These discourses reflect particular worldviews, ideologies, or power relations, and the researcher examines how they influence the understanding of the topic.

Analyzing language use

The researcher focuses on the language features used in the discourse, such as word choice, metaphors, tone, and sentence structure. These features reveal how social norms, power dynamics, and ideologies are embedded in everyday language.

Examining power and ideology

Discourse analysis looks at how language reinforces or challenges power relations and social hierarchies. Researchers explore how certain discourses privilege particular viewpoints or marginalize others, shedding light on the role of language in maintaining social order.

Interpretation and implications

In the final phase, the researcher interprets the findings and discusses the implications of the discourses identified. The analysis might reveal how language contributes to social inequalities, or how it is used to assert authority or legitimize certain practices within a given context.

Framework analysis

Framework analysis can be used when research has predefined objectives or questions. Initially developed by Ritchie and Spencer (2003), it is widely used in applied research such as policy analysis or healthcare studies. The approach is structured and transparent, making it well-suited for large datasets. Framework analysis allows for the organization of data into themes and sub-themes within a matrix, ensuring the data is rigorously examined and aligned with the research objectives. The use of matrices ensures that the data is organized both thematically and by case, providing a clear structure for comparison.

Familiarization

In the first step, the researcher becomes immersed in the data by thoroughly reading through the transcripts, field notes, or documents. This initial phase is crucial for gaining a comprehensive understanding of the data. Researchers often take notes and highlight initial ideas that appear significant.

Identifying a thematic framework

After familiarization, a thematic framework is developed. This framework emerges from the key research questions, theory, or preliminary findings during familiarization. The framework acts as a guide for analyzing the data and is made up of important themes and sub-themes.

Indexing

The researcher applies the thematic framework to the data by indexing, or coding, sections of the data according to relevant themes. The indexing process links specific portions of the data with relevant themes from the framework, ensuring each section of data is categorized systematically.

Charting

In this phase, the data is charted into a matrix. The matrix organizes data according to themes (rows) and individual cases or participants (columns), creating a structured format that enables easy comparison across different cases. The charting process involves summarizing data from each case under the appropriate thematic headings.

Mapping and interpretation

The final stage involves analyzing the data within the framework, identifying patterns, relationships, and contrasts across the themes and cases. Researchers map out the key findings, drawing conclusions based on the thematic framework and using the matrix to ensure that all relevant aspects of the data are accounted for. This stage is crucial for developing insights that answer the research questions.

Phenomenological analysis

Phenomenological analysis is a method used to explore and understand individuals' lived experiences. It is grounded in the philosophical tradition of phenomenology, which seeks to uncover the essence of experiences. van Manen (1990)´s approach is valuable when the research focuses on how individuals experience and perceive specific phenomena, such as illness, loss, or life transitions. The analysis aims to capture the richness of these experiences, distilling them into essential themes that describe the core essence of the phenomenon.

Bracketing

The researcher begins by bracketing or setting aside their preconceived notions and assumptions about the phenomenon being studied. This is essential to ensure that the analysis focuses solely on the participants' experiences without the researcher influencing the interpretation.

Immersion in the data

The researcher reads and re-reads the interview transcripts, fully absorbing the participants' descriptions of their experiences. During this phase, the researcher remains attentive to significant phrases or sentences that stand out as key to understanding the participants' experiences.

Identifying themes

Key themes are extracted from the data that reflect essential aspects of the participants' experiences. These themes often relate to emotions, perceptions, and reactions to specific situations, and they represent the commonalities across different participants' accounts.

Synthesizing themes

After identifying themes, the researcher synthesizes them into a coherent description that captures the core essence of the lived experience. This involves interpreting the meaning behind each theme and understanding how the themes interrelate.

Writing the findings

The final report provides a rich, detailed account of the phenomenon, highlighting the essential themes and using participant quotes to illustrate key points. The goal is to present the findings in a way that conveys the depth and complexity of the participants' experiences.

Less common methods of analyzing interview data

Conversational analysis

Conversational analysis (CA) is a method used to examine the structure and pattern of talk in social interactions. Developed by Sacks, Schegloff, and Jefferson (1974), it focuses on understanding how conversations unfold in real-time, analyzing the turn-taking mechanisms, repairs, and sequences within dialogue. CA aims to uncover the implicit rules and social norms that govern everyday conversation. This method is particularly useful for studying the micro-interactions between individuals, such as those that occur during interviews, debates, or casual conversations.

Transcription

The researcher begins by transcribing the conversation in detail, paying close attention to pauses, interruptions, overlaps, tone, and other non-verbal cues. The transcription is usually highly detailed, with symbols used to indicate timing, emphasis, and changes in speech patterns.

Turn-taking analysis

A key focus of CA is understanding how speakers manage turn-taking during conversations. The researcher examines how participants signal when they wish to speak, how they take turns, and how they yield the floor to others. This analysis reveals the social norms guiding conversational flow.

Sequence organization

Conversations often follow particular sequences (e.g., question-answer pairs, greetings, and responses). Researchers analyze how these sequences unfold and how participants maintain or disrupt the expected flow of interaction. This includes analyzing how meaning is constructed through these sequences.

Repair mechanisms

When misunderstandings or conversational breakdowns occur, participants often use repair strategies to fix the interaction. Researchers examine how participants address these issues, looking for patterns in how they clarify, repeat, or rephrase their speech.

Conclusion and social implications

Based on the analysis, the researcher draws conclusions about the social norms and rules governing conversational interactions. This analysis helps to reveal broader social structures and expectations reflected in everyday communication.

Interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA)

Interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) is a qualitative research method that aims to explore how individuals make sense of their personal and social experiences. It is rooted in phenomenology and hermeneutics, focusing on understanding the meaning behind lived experiences. Smith, Flowers, and Larkin (2009) have been instrumental in developing IPA as a research method, emphasizing its use in psychology, health, and education. IPA is particularly useful for studies that explore subjective experiences, such as coping with illness or navigating personal challenges, and it allows for a deep, interpretative understanding of the data.

Reading and immersion

The researcher starts by immersing themselves in the interview transcripts, carefully reading and reflecting on the participants’ accounts. This step ensures that the researcher is fully engaged with the data before moving to analysis.

Initial coding

The researcher identifies significant elements within the data by applying codes to sections of the transcript. These codes capture the meaning of the participants' experiences in a concise form and are the foundation for later theme development.

Theme development

After coding, the researcher looks for patterns or themes across the data. Themes reflect the participants’ key concerns and meanings, and they help to explain how participants make sense of their experiences. Themes are grouped and structured to reflect their relationships.

Interpretation

The researcher moves beyond describing themes to interpret the deeper meaning behind them. This interpretative process involves understanding the participants' lived experiences within their broader social and psychological contexts.

Synthesis and reporting

The final stage involves writing a report that weaves together themes and interpretations, providing a detailed and nuanced account of how participants experience and make sense of their world. Direct quotes from participants are used to illustrate key themes.

How can ATLAS.ti help with interview data analysis?

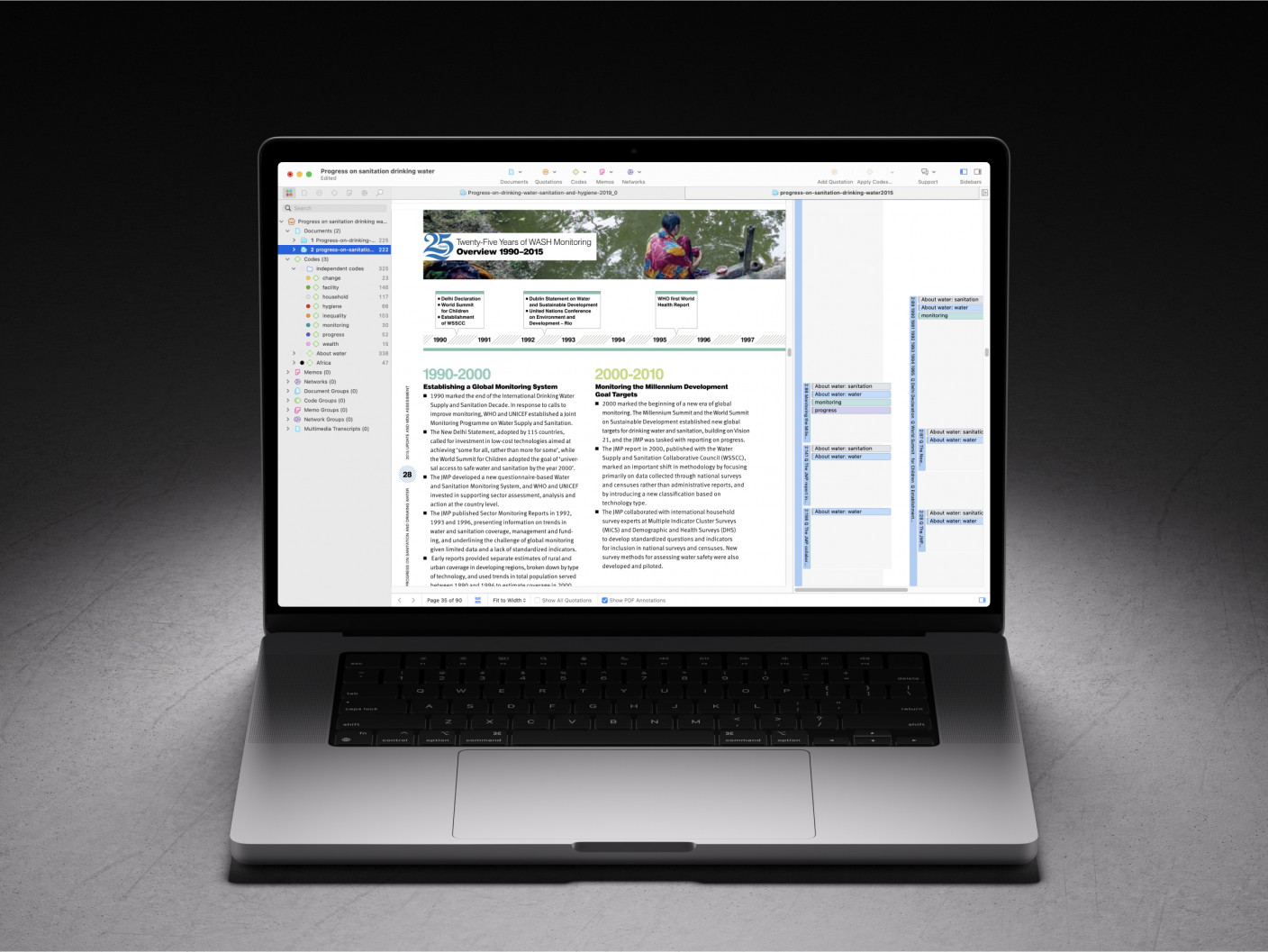

ATLAS.ti is an advanced qualitative analysis software designed to help researchers efficiently manage and analyze interview data. Whether you're working alone or in a team, with text, audio, or video formats, ATLAS.ti provides a wide array of tools that facilitate the coding and interpretation process.

Import interview transcripts and recordings: Researchers can easily import interview data and begin identifying key themes by highlighting relevant segments of text or annotating timestamps in media files.

Write reflections and notes in memos: One of the most important tools for researchers are memos, where you can document insights, reflections, and emerging ideas throughout the analysis process, ensuring that important observations are captured.

Code your data according to your chosen methodology: Coding and analyzing data in ATLAS.ti is extremely flexible, so you can follow whichever methodology is best suited to your research. You can highlight any segment of data, write notes, and attach codes. Create your own codes, use in vivo codes, easily re-use already existing codes, or even explore AI-suggested codes.

Use AI as a virtual assistant: ATLAS.ti also includes a wide range of AI-driven tools, which can automate repetitive tasks and offer a different perspective into the data.

Intentional AI coding: Automatically generates descriptive codes by analyzing your interview transcripts. It helps identify key themes and phrases.

Conversational AI: Ask any questions about your data using natural language, and the AI-driven chatbot will provide answers based on your selected data. It will also show you the segments of data on which its answers are based, so you can easily explore your whole dataset.

Sentiment analysis: This tool analyzes the emotional tone of the text, automatically coding positive, negative, and neutral sentiments within your interview data. It helps researchers quickly assess participant attitudes and reactions.

Named entity recognition (NER): AI identifies key entities such as names, organizations, and locations within your text, offering a faster way to code significant elements in the interviews.

Concept detection: Automatically highlights relevant concepts or keywords, presenting a word cloud that helps in understanding the main topics and sub-themes of the interview.

Opinion mining: This feature analyzes opinions and sentiments related to identified concepts, helping to dig deeper into participant views and attitudes.

Visualize your data and analysis in networks: Use networks to brainstorm ideas, build conceptual frameworks, or simply draw out the story of your research. Any part of your project can be visualized in a network, including data quotations, code frequencies, and your notes.

Display your data to explore overarching patterns: Examine frequencies of codes across your data and dig into patterns of co-occurrences among your codes with tools that display your data in tables, graphs, and Sankey diagrams. You can explore the bigger picture of your research and develop more nuanced insights.

Conclusion

Interview analysis lies at the heart of qualitative research, transforming raw conversations into rich, meaningful insights that shape our understanding of human experiences. By employing structured and systematic approaches such as thematic analysis, grounded theory, or narrative analysis, researchers can uncover the underlying patterns and themes within qualitative data. These methods help analyze qualitative data and allow for deeper exploration of individual perspectives and collective experiences, contributing valuable findings to the research landscape. Tools like ATLAS.ti further enhance this process, simplifying the coding process, helping to identify themes, and providing robust frameworks for analyzing qualitative interview data. Whether the goal is to generate theory or reveal hidden sentiments through sentiment analysis, effective interview analysis is essential for translating complex human interactions into clear, actionable research outcomes.

References

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage Publications.

- Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine Publishing.

- Krippendorff, K. (1980). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Sage Publications.

- Ritchie, J., Spencer, L., & O’Connor, W. (2003). Carrying out qualitative analysis. In J. Ritchie & J. Lewis (Eds.), Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers (pp. 219–262). Sage Publications.

- Riessman, C. K. (2008). Narrative methods for the human sciences. Sage Publications.

- Fairclough, N. (1992). Discourse and social change. Polity Press.

- van Manen, M. (1990). Researching lived experience: Human science for an action sensitive pedagogy. SUNY Press.

- Sacks, H., Schegloff, E. A., & Jefferson, G. (1974). A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language, 50(4), 696–735. https://doi.org/10.2307/412243

- Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2009). Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method, and research. Sage Publications.

- Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687