- What is Mixed Methods Research?

- Advantages of Mixed Methods Research

- Challenges in Mixed Methods Research

- Common Mistakes in Mixed Methods Research

- Mixed Methods Research Paradigms

- Validity & Reliability in Mixed Methods Research

- Ethical Considerations in Mixed Methods Research

- Mixed Methods vs. Multiple Methods Research

-

Mixed Methods Research Designs

- Introduction

- Mixed methods research principles

- Major mixed methods designs

- How to select a design?

- Convergent parallel design

- Explanatory sequential designs

- Exploratory sequential designs

- Embedded design

- Complex mixed methods research design

- Transformative designs

- Multiphase design

- Summary - Mixed Methods Research Designs

- How to Choose the Right Mixed Methods Design

- Convergent Parallel Design

- Explanatory Sequential Design

- Exploratory Sequential Design

- Embedded Mixed Methods Research Design

- Transformative Mixed Methods Design

- Multiphase Mixed Methods Research Design

- How to Conduct Mixed Methods Research

- Sampling Strategies in Mixed Methods Research

- Data Collection in Mixed Methods Research

- Triangulation in Mixed Methods Research

- Data Analysis in Mixed Methods Research

- How to Integrate Quantitative & Qualitative Data?

- How to Interpret Mixed Methods Research Findings?

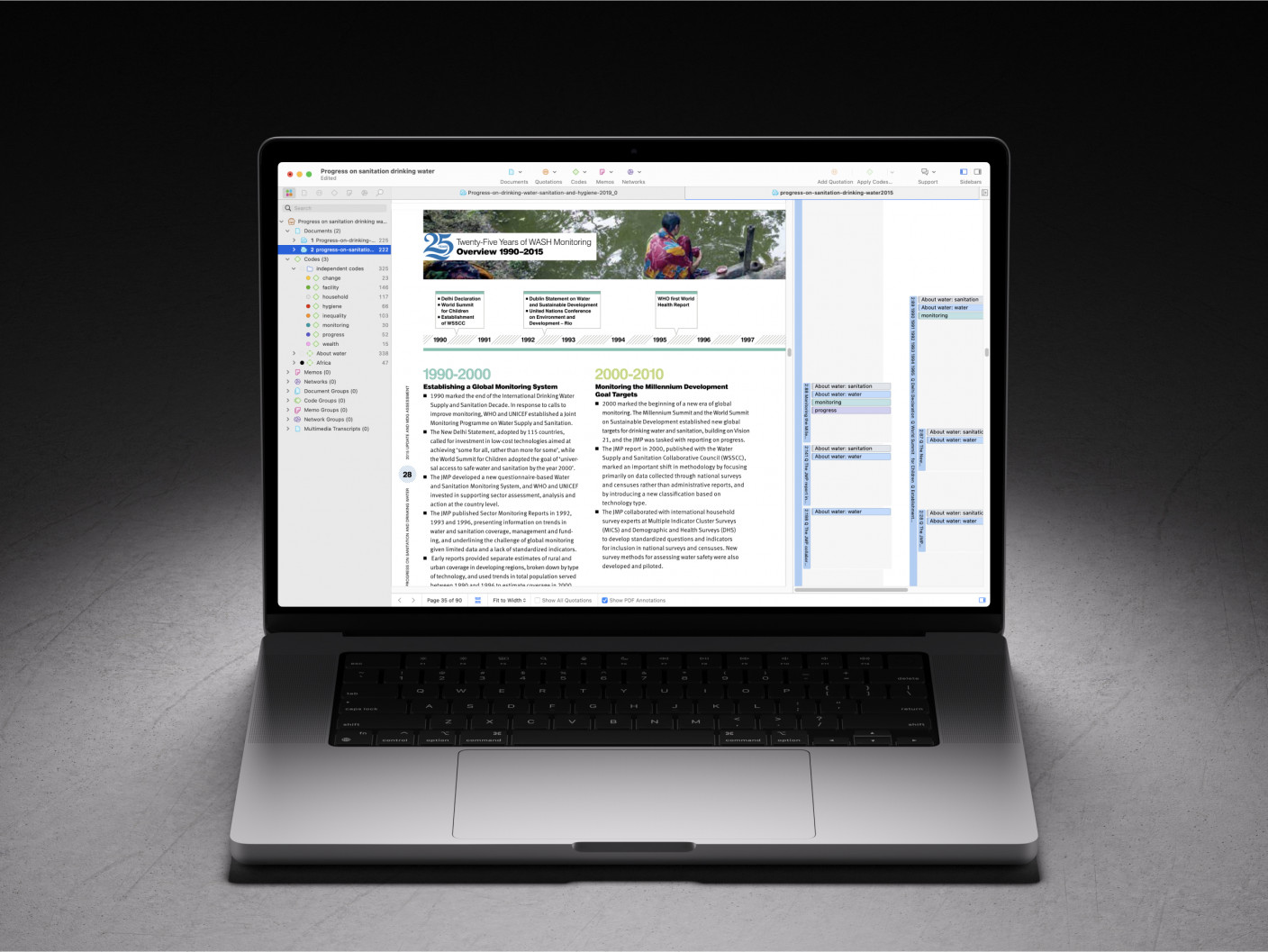

- Software Tools for Mixed Methods Data Analysis

- How to Write a Mixed Methods Research Proposal

- How to Write a Mixed Methods Research Paper?

- Reporting Results in Mixed Methods Research

- Mixed Methods Research Examples

- How to cite "The Guide to Mixed Methods Research"

Mixed Methods Research Designs

Conducting mixed methods research can be a demanding research process as it requires the integration of quantitative and qualitative data. Since the late 1980s, researchers have identified different approaches and designs that have helped navigate this complex research process. In this article we will go through the background, different designs, and approaches that researchers have identified over time.

Introduction

In mixed methods research, designs are procedures for collecting, analyzing, interpreting, and reporting qualitative and quantitative data for studies. They serve as the guide for the research process, help a researcher make decisions, and set the logic for the final interpretations. Once a researcher decides to do mixed methods research, the next step is to choose the design. There are major types of mixed methods designs with their own history, purpose, considerations, assumptions, procedures, strengths and challenges.

However, before we dive into each design, it is important to mention that designs can be fixed but also emergent. In fixed mixed methods designs, the use of quantitative and qualitative research is predetermined and planned at the start of the research process. On the other hand, emergent mixed methods designs arise due to issues that develop during the study and when a second approach is added because one method was found inadequate. These categories are not seen as a dichotomy but as endpoints along a continuum.

Researchers usually identify their design using one of two approaches. The first one, the typology-based approach, relies on selecting from a predefined set of mixed methods designs that have been extensively discussed in the literature. These designs are categorized and classified based on their purposes and features. Researchers use this approach as a guiding framework to select or adapt a design that aligns with their study's purpose and research questions. Typologies offer a structured way to think about mixed methods research and are particularly useful for those new to this field.

On the other hand, the dynamic approach is a more flexible, emergent design that focuses on integrating various components of the study rather than adhering to a fixed design from a typology. It considers the interrelationships between elements like the study's purpose, conceptual framework, research questions, methods, and validity considerations. This approach allows for adaptability and interaction among study components throughout the research process.

Mixed method design principles

According to Creswell, researchers designing a mixed methods study must consider four general principles:

- Mixed methods designs can be fixed from the start or changed once the study is underway.

- Researchers must consider their approach to research design and weigh the use of a typology-based or dynamic approach.

- The design must match the research problem and research question.

- Researchers should articulate at least one reason why they are mixing methods.

Based on these principles, researchers should make four important decisions that will define the design. These will address the different ways that the quantitative and qualitative strands of the study relate to each other. A strand is a component of a study that encompasses the basic process of conducting quantitative or qualitative research such as posing a question, collecting data, analyzing data, and interpreting results based on that data (Teddlie & Tashakkori, 2009). The four decisions are:

- Level of interaction: If the strands will remain independent or be interactive.

- Relative priority: If they will have equal or unequal priority for addressing the research question.

- Timing: Whether they are implemented concurrently, sequentially or in multiple phases.

- Procedures: How they will be mixed and integrated.

These important decisions, along with the logic best suited to the research problem, are the foundation for selecting a mixed methods design. Each design option will vary on these decision points.

Major mixed methods research designs

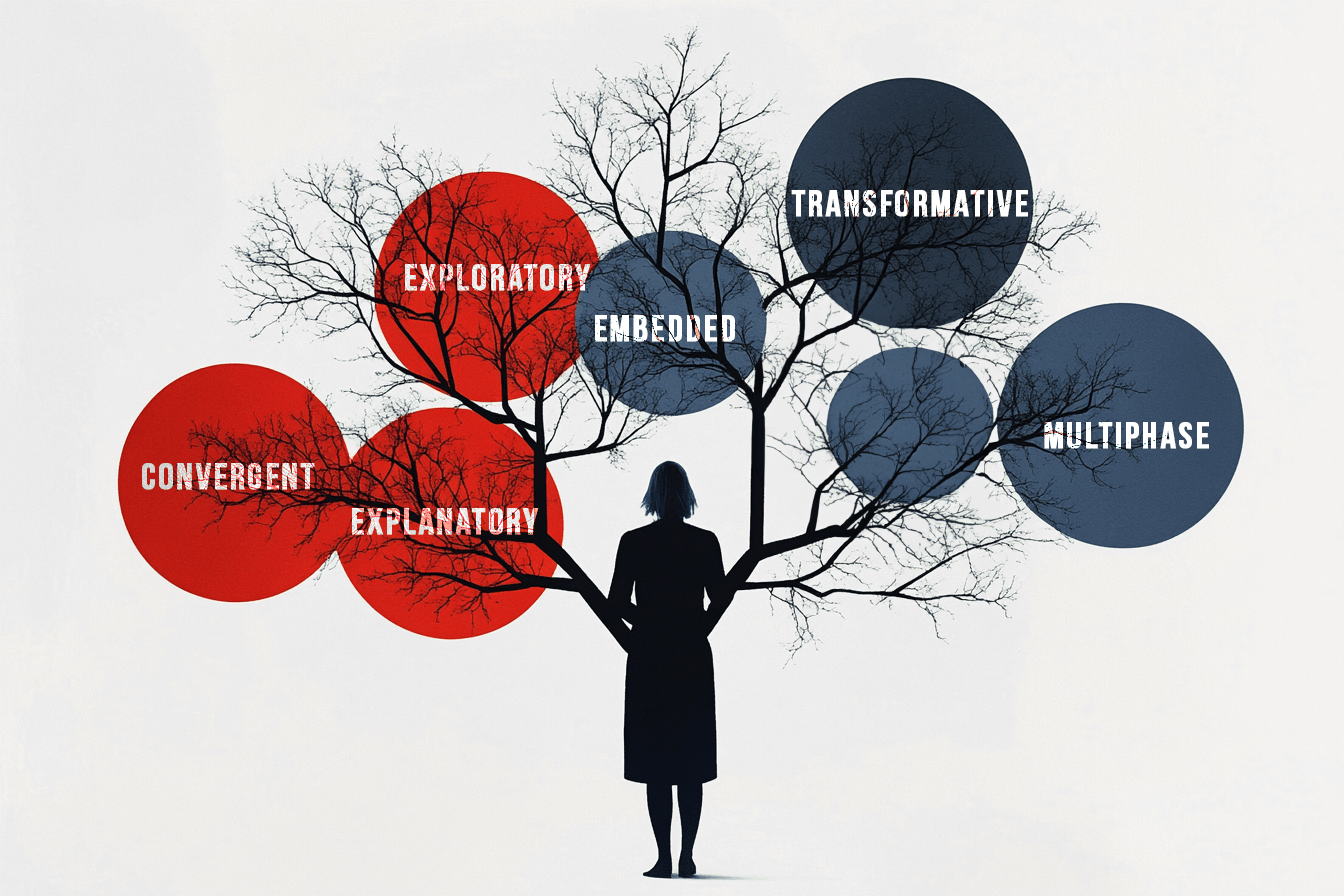

According to Creswell (2017), six major designs are currently used: convergent, explanatory, exploratory, embedded, transformative and multiphase designs. Each design has a different purpose and incorporates different strategies for integrating qualitative and quantitative data. The first four (convergent, explanatory, exploratory, and embedded) are the basic designs while the last two (transformative and multiphase) bring multiple design elements together.

In this article, we will go through the basics of each design and provide examples. Throughout this guide, we will explain their characteristics in greater depth and how they are conducted.

How to select a design?

The choice of design depends on several factors, including the research goals, available resources, and the desired level of integration between qualitative and quantitative methods. Researchers might also want to consider whether they will use separate software for the quantitative and qualitative analyses, or if they can rely on a single software for all their analyses. Tools like ATLAS.ti or NVivo are very useful for researchers conducting mixed methods research

Each design offers unique advantages and challenges, and researchers must align their choice with the study’s objectives. Each design also serves different purposes and is based within different philosophical assumptions.

Convergent designs are efficient for simultaneous data collection, while sequential designs—explanatory or exploratory—provide a structured pathway for integrating different data types.

Integration techniques play a critical role in mixed methods research. In convergent designs, merging occurs at the interpretation stage, where researchers compare and contrast findings. In sequential designs, integration involves building or connecting phases; for example, qualitative data in the exploratory design guides the development of quantitative instruments. These strategies require careful attention to ensure that the qualitative and quantitative components complement each other, yielding cohesive and meaningful results.

With these designs, researchers can address multifaceted research questions that neither qualitative nor quantitative methods alone could sufficiently explore. Creswell’s framework provides a robust foundation for integrating diverse data types and gives a deeper understanding of complex issues. Each design offers distinct pathways to achieve comprehensive and actionable research outcomes.

Convergent parallel designs

A convergent parallel design was at first called parallel or concurrent but the name now focuses on the intent rather than the process (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2017). In this design, qualitative and quantitative data are collected simultaneously, analyzed separately, and merged at the end.

This design requires careful planning as both datasets are equally prioritized and complement each other. A major advantage is its efficiency and its ability to collect data parallelly. A disadvantage is the complexity of the data integration phase when mixing the two datasets. It is most effective when both data types carry equal weight in the study's conclusions.

When is a convergent parallel design used?

This type of design is used when there is a need to cross-check or validate findings by comparing both kinds of data collection. For example, survey data may indicate a trend that can be explained with interviews. It is useful when the researcher is exploring and reconciling any contradictions between numerical trends and contextual observations. It is commonly used in social, health, and educational research, as well as to cater to diverse audiences such as policymakers, practitioners, or other stakeholders.

Explanatory sequential designs

The explanatory sequential design consists of two phases. It starts with collecting and analyzing quantitative data, followed by a qualitative phase that helps explain and build on the quantitative results. This design is particularly valuable in fields with strong quantitative traditions, where researchers may seek deeper insights to explain or elaborate on quantitative results.

This design unfolds in a clear sequence: quantitative data collection and analysis are completed first, followed by qualitative exploration. The quantitative findings directly inform the development of qualitative questions and make sure that the qualitative phase addresses specific aspects of the initial results. While this design is advantageous for clarifying complex quantitative findings, it requires careful planning to maintain alignment between the two phases. A common challenge is ensuring that the qualitative sample provides rich and relevant data to contextualize the quantitative results.

The sequential nature of this design can be time-intensive, requiring separate data collection, analysis, and interpretation phases. Integrating findings into a cohesive narrative can be complex, demanding careful planning. Additionally, ensuring consistency between quantitative and qualitative samples can require extra effort, making the process resource-intensive.

When is an explanatory sequential design used?

The explanatory sequential design is used when researchers need to understand the reasons, contexts, or mechanisms underlying quantitative findings. It is particularly effective in studies where the initial quantitative phase identifies trends, patterns, or outliers that require further exploration through qualitative methods. This design is chosen when the numerical data alone cannot fully explain complex phenomena and when qualitative insights can provide additional depth and context.

Explanatory sequential designs are widely used in health services, education, and social sciences. Quantitative surveys might reveal healthcare disparities, prompting qualitative exploration of underlying barriers. Similarly, in education, standardized test results can guide interviews with teachers to understand instructional methods. This design is ideal for studies needing both broad overviews and detailed explorations.

In complex topics, explanatory sequential designs are valuable for building a foundation for future studies. Quantitative data outlines broad patterns, while qualitative insights provide the depth needed to inform actionable conclusions or refine research instruments.

Exploratory sequential designs

In contrast to the explanatory sequential design, the exploratory sequential approach starts with qualitative data collection and analysis, which then informs the subsequent quantitative phase. The exploratory sequential design is particularly useful when existing quantitative tools are inadequate or irrelevant to the specific context of the study.

The qualitative phase provides an in-depth exploration of the phenomenon, while the subsequent quantitative phase tests and generalizes the findings to a broader audience. This design requires meticulous planning to translate qualitative findings into quantitative measures. While the two-phase structure provides depth and breadth, it can be time-consuming and resource-intensive. Additionally, researchers must navigate the challenge of converting qualitative themes into quantifiable variables and ensuring the reliability and validity of the resulting quantitative instruments.

The qualitative phase is often conducted through interviews, focus groups, or observations that uncover themes, insights, or constructs that may inform the subsequent quantitative phase (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2017). Once the qualitative data has been analyzed, these findings guide the development of quantitative instruments, such as surveys or experiments, which allow for the validation and generalization of the results on a larger scale (Grech & Grech, 2020; Teddlie & Yu, 2007).

A key strength of the exploratory sequential design lies in its ability to integrate the depth of qualitative data with the generalizability of quantitative findings. This integration provides a holistic understanding of the research problem, balancing contextual richness with empirical rigor (Fetters et al., 2013).

Despite its strengths, the exploratory sequential design presents several challenges. It is often time-consuming, as each phase must be completed sequentially, and the process of translating qualitative findings into quantitative measures can be complex and iterative (Fetters et al., 2013; Grech & Grech, 2020). Nevertheless, this design's capacity to address nuanced research questions and develop robust tools makes it an indispensable method in mixed methods research.

When is an exploratory sequential design used?

Researchers often use this approach to generate hypotheses, identify key variables, or develop tools for broader validation. This design is ideal for research areas that are underexplored or lack established measures. It is especially valuable when creating new tools or measurement instruments. Qualitative data may reveal nuanced constructs or dimensions of a phenomenon that existing tools fail to capture. These findings can be operationalized into survey items or experimental variables, ensuring that the quantitative phase is directly aligned with participants' lived experiences. In a study investigating strokes, Grech and Grech (2020) used an exploratory sequential design to first gather in-depth qualitative insights from interviews, which were then used to develop a quantitative survey assessing the broader population's understanding.

Additionally, exploratory sequential design is ideal for addressing complex problems, such as health disparities or educational inequities, where qualitative insights can illuminate context-specific challenges, and quantitative data can establish patterns or trends across broader populations (Fetters et al., 2013; Creswell, 2018).

Embedded designs

The embedded design integrates a secondary method (qualitative or quantitative) into a dominant primary method to enrich the depth and breadth of the study. This design is particularly effective when the primary method alone cannot adequately address all aspects of the research question(s).

In an embedded design, the secondary method serves a complementary role. It is often used to answer ancillary questions or to provide context and validation for the primary data. The integration typically occurs at specific points, such as during data collection or analysis, rather than being woven throughout the entire study.

Embedded designs are also beneficial when different types of data are needed at specific stages of the research process. They are used to answer sub-questions that arise within the main research question but may require a different methodology.

One of the key challenges of the embedded design is maintaining a balance between the two methods. Researchers must ensure that the secondary method complements rather than overshadows the primary method. Additionally, aligning the timing and integration points between methods can be complex.

When is an embedded design used?

Embedded designs are often used to develop instruments, refine interventions, or understand contextual factors. Qualitative data may inform the development of survey instruments that are later used in large-scale quantitative studies. It can also be used when evaluating an intervention or program to understand the contextual factors that influence outcomes. When existing instruments are insufficient, embedded qualitative methods can identify culturally or contextually relevant variables for creating or refining tools.

This design is particularly effective in addressing complex, multilevel research questions, and it is common in health sciences, education, and social sciences. For example, if a researcher wants to develop a peer intervention to help people develop strategies for resisting pressure to smoke, the researcher could conduct focus groups to learn when the pressure is felt and how some resist it. With these results, the researcher could develop a relevant intervention and test it with a quantitative design that involves different populations. This design is also common in program evaluations, where researchers may need to combine quantitative data on outcomes with qualitative assessments of implementation processes.

Complex mixed methods research designs

Complex mixed methods designs extend beyond the foundational core designs (convergent, explanatory, exploratory, and embedded). These advanced frameworks are tailored to address intricate research questions that require integrating multiple phases, methodologies, or theoretical approaches. They are characterized by their adaptability, multi-stage structures, and the ability to incorporate diverse philosophical worldviews and social contexts (Creswell, 2018; Fetters, Curry, & Creswell, 2013).

Key characteristics

- Complex designs involve integrating qualitative and quantitative data at the data collection or analysis phases and within the theoretical frameworks, intervention planning, and interpretation of results.

- These designs are often customized to meet specific research objectives, such as addressing longitudinal questions, testing interventions, or evaluating systems.

- Many complex designs emphasize stakeholder engagement, social justice, or participatory processes, making them suitable for community-based or action-oriented research.

- They often include multiple phases of data collection, analysis, and integration, sometimes over extended periods, to answer nuanced or layered research questions.

Transformative designs

In a transformative design, a researcher works within a specific "transformative" theoretical framework, which is rooted in the belief that research should address issues of social justice, power imbalances, and inequities. All decisions in the research process—ranging from the formulation of research questions to data collection, analysis, and interpretation—are made to align with this framework. This approach emphasizes the active role of research in advocating for marginalized or underrepresented groups and seeks to create positive social change through participatory methods and the inclusion of diverse perspectives

Unlike traditional positivist research paradigms that focus primarily on objective inquiry, transformative design emphasizes the lived experiences of marginalized communities, integrating these perspectives into the research process to foster actionable outcomes. By embedding social justice principles into research objectives, transformative designs seek to catalyze meaningful change in policies, practices, and societal structures.

A key feature of a transformative design is its collaborative approach, which actively involves participants in the research process. This partnership ensures that the voices and perspectives of underrepresented groups are central to the study. Researchers work alongside participants to co-create research questions, interpret findings, and identify actionable strategies. This inclusive approach fosters trust and ensures that the research outcomes are relevant and reflective of the participants' lived experiences. Transformative mixed-method design prioritizes collaboration, challenges traditional power dynamics in research, and creates a space where contributions from all stakeholders are equally valued.

Transformative designs frequently employ theoretical frameworks such as critical theory, feminist perspectives, or disability studies, which guide data analysis and interpretation. These frameworks offer insights into the systemic structures that perpetuate inequities, steering the research toward actionable solutions. For example, critical theory helps identify power imbalances, while feminist perspectives may focus on gender-specific issues. By using these frameworks, transformative designs help researchers address the root causes of inequities rather than merely document their symptoms.

In practical terms, transformative designs have been applied in fields such as health care, education, and community development to address issues like discrimination, access to resources, and systemic oppression. Findings from transformative studies often guide the development of policies, interventions, and community programs. These applications are designed to address immediate needs while contributing to long-term systemic changes. Transformative designs connect research and activism, ensuring that scholarly inquiry translates into benefits for marginalized communities.

Multiphase design

In a multiphase design, researchers conduct multiple stages or phases of data collection and analysis. Each phase builds upon the results of the previous ones to address a complex research question comprehensively. One of its unique characteristics is its sequential structure. For example, an initial qualitative phase might involve interviews that inform the development of quantitative tools, such as surveys. In later phases, qualitative methods may again be used to go deeper into trends or anomalies identified during quantitative analysis. This process creates a cohesive and thorough exploration of the research question.

The integration of findings across multiple phases is another essential feature of this design. Through careful synthesis, researchers can combine quantitative data, which provides breadth and generalizability, with qualitative insights that offer depth and context. For example, in public health studies, a multi-phase design might first identify cultural barriers to healthcare access through qualitative interviews, then measure their prevalence via surveys, and finally explore intervention strategies in focus groups.

The multi-phase design is particularly suited for addressing complex, layered research problems. Its longitudinal and iterative nature allows researchers to adapt to new findings, ensuring flexibility and responsiveness. Whether applied to health services, education, or social sciences, this approach provides a powerful means to explore multifaceted phenomena comprehensively. Its strength lies in its ability to generate robust, actionable insights by integrating the diverse strengths of qualitative and quantitative methodologies.

Summary

- Key decisions when designing a mixed methods study: Determine the interaction level, assign priority to strands, choose the timing (concurrent, sequential, or multiphase), and decide how and when to integrate qualitative and quantitative data.

- Mixed methods design principles: Align the design with the research problem, clarify the rationale for mixing methods, decide between fixed or emergent approaches, and choose a typology-based or dynamic design approach.

- Basic designs: Utilize convergent parallel, explanatory sequential, exploratory sequential, or embedded designs to collect, analyze, and integrate qualitative and quantitative data based on the study’s goals.

- Complex designs: Apply transformative or multiphase designs to address complex research questions through theoretical frameworks, participant collaboration, and multiple phases of mixed methods integration.

- Convergent parallel design: Collect qualitative and quantitative data simultaneously, analyze them separately, and merge the results for comprehensive interpretation.

- Explanatory sequential design: Gather quantitative data first, then use qualitative data to explain or elaborate on the quantitative findings.

- Exploratory sequential design: Start with qualitative data to explore a topic, then use the findings to guide subsequent quantitative data collection and analysis.

- Embedded design: Integrate one method (qualitative or quantitative) within the other as a supplemental component to provide additional context or insights.

- Transformative design: Use a specific theoretical framework to address social justice or systemic change, integrating qualitative and quantitative data with active participant collaboration.

- Multiphase design: Combine multiple mixed methods designs across several phases to address complex, layered research questions with iterative data collection and analysis.

References

- Creswell, J. W. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Fetters, M. D., Curry, L. A., & Creswell, J. W. (2013). Achieving integration in mixed methods designs—Principles and practices. Health Services Research, 48(6), 2134–2156.

- Grech, P., & Grech, R. (2020). Stroke knowledge: Developing a framework for data integration in a sequential exploratory mixed method study. Research Methods in Medicine & Health Sciences, 2(2), 68–81.

- Teddlie, C., & Yu, F. (2007). Mixed methods sampling: A typology with examples. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(1), 77–100.