- What is Mixed Methods Research?

- Advantages of Mixed Methods Research

- Challenges in Mixed Methods Research

- Common Mistakes in Mixed Methods Research

- Mixed Methods Research Paradigms

- Validity & Reliability in Mixed Methods Research

- Ethical Considerations in Mixed Methods Research

- Mixed Methods vs. Multiple Methods Research

- Mixed Methods Research Designs

- How to Choose the Right Mixed Methods Design

- Convergent Parallel Design

- Explanatory Sequential Design

- Exploratory Sequential Design

- Embedded Mixed Methods Research Design

- Transformative Mixed Methods Design

- Multiphase Mixed Methods Research Design

- How to Conduct Mixed Methods Research

- Sampling Strategies in Mixed Methods Research

- Data Collection in Mixed Methods Research

- Triangulation in Mixed Methods Research

- Data Analysis in Mixed Methods Research

- How to Integrate Quantitative & Qualitative Data?

- How to Interpret Mixed Methods Research Findings?

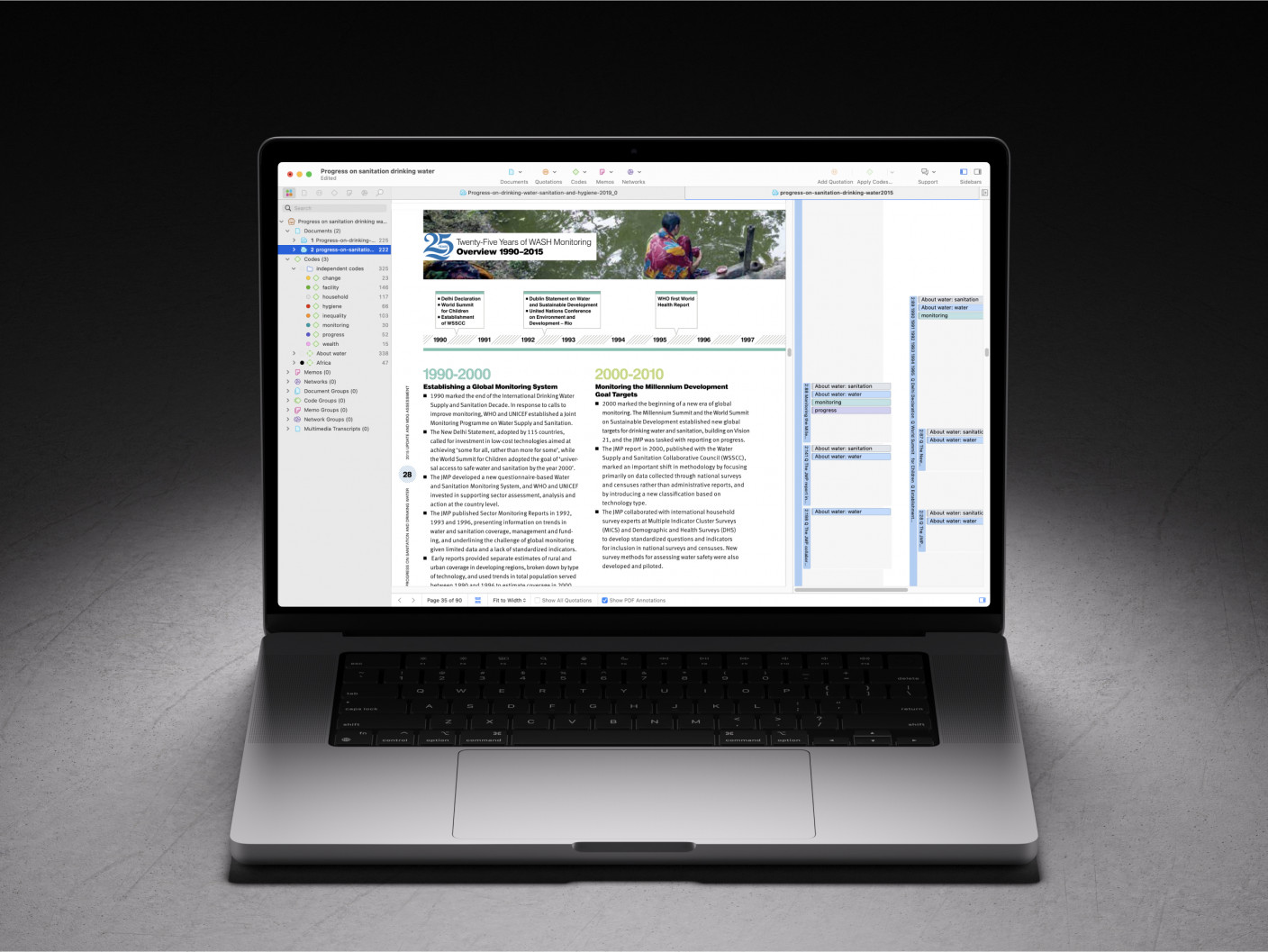

- Software Tools for Mixed Methods Data Analysis

- How to Write a Mixed Methods Research Proposal

- How to Write a Mixed Methods Research Paper?

- Reporting Results in Mixed Methods Research

- Mixed Methods Research Examples

- How to cite "The Guide to Mixed Methods Research"

Challenges in Mixed Methods Research

The mixed methods approach, which integrates quantitative and qualitative data within a single study, has gained popularity for its ability to provide a comprehensive understanding of complex issues. Despite its advantages, conducting mixed-methods research has challenges that researchers must address throughout the research process. Read this article to learn more about the disadvantages of mixed methods.

Introduction

Mixed methods research provides a powerful framework for investigating complex social phenomena by combining the strengths of qualitative and quantitative approaches. This approach allows you to capture numerical trends while exploring the contextual depth of participants' experiences. It enhances validity by triangulating findings, explaining unexpected results, and offering multiple perspectives on a research question. You can also use mixed methods to develop more nuanced theoretical frameworks and gain deeper insights into statistical patterns.

Integrating qualitative and quantitative data introduces several challenges that require careful navigation. You must carefully design the study, allocate sufficient time and resources for dual data collection, and address philosophical differences between methodological paradigms. Data integration requires thoughtful planning to align qualitative themes with quantitative patterns, ensuring that findings form a cohesive narrative rather than remaining disconnected.

Despite these challenges, mixed methods research remains a valuable and versatile tool. With careful planning and intentional integration, you can maximize its benefits and produce rigorous, meaningful results.

Complexity in design and execution

Mixed methods research requires a detailed design plan to integrate qualitative and quantitative components effectively. At the start of any mixed methods study, it is important to decide on the purpose of your qualitative and quantitative data: Do you want one to lay the groundwork that the other can then build on, or do you want both to inform one another iteratively? Both types of data should also work together to answer your research question. Figuring out why you want to collect your qualitative and quantitative data, and how they fit together, can help you design your mixed methods study.

Researchers must determine whether the data collection will be concurrent (both types of data collected simultaneously) or sequential (one method follows the other), and this decision has implications for the timing, scope, and alignment of the research. For example, a study exploring the relationship between workplace stress and productivity might use quantitative surveys to measure stress levels and productivity metrics, followed by qualitative interviews to explore employees’ experiences in more depth. Alternatively, if you want to develop a new survey to explore workplace stress and productivity, you could first conduct qualitative interviews to inductively explore which concepts and interrelationships are relevant. Based on these insights, you can design your new survey and then administer and validate it. Without proper synchronization between the qualitative and quantitative elements, the results may appear disjointed or contradictory, undermining the credibility of the research. Effective design requires expertise, collaboration, and a clear theoretical framework to ensure compatibility between the methods (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018; Grech & Grech, 2021).

Time and resource intensive

Conducting a mixed-methods study can be more demanding in terms of time and resources compared to single-method approaches. Researchers must budget time for designing and conducting (at least) two distinct types of data collection, analyzing each dataset independently, and then integrating the findings. For example, in a public health study assessing the effectiveness of a vaccination campaign, quantitative surveys might measure vaccination rates while qualitative focus groups explore barriers to vaccine uptake. This approach requires significant investment: trained staff for conducting surveys and focus groups, transcribers for qualitative data, software for statistical and thematic analyses, and experts to synthesize the findings. Moreover, delays in one phase, such as transcription or coding of interview data, can set back the entire project timeline. Financially, the dual requirements of mixed methods—such as hiring both statisticians and qualitative analysts—can strain budgets, making this approach less feasible for small-scale or low-resource projects (Migiro & Magangi, 2011; Vivek & Nanthagopan, 2021).

Expertise required in both methodologies

Mixed methods research demands proficiency in both qualitative and quantitative techniques, a requirement that poses significant challenges for many researchers. For instance, a mixed methods study on urban housing policies might involve statistical analysis of survey data to measure housing satisfaction levels and thematic analysis of interviews to capture the nuanced experiences of residents. A researcher trained primarily in qualitative methods may struggle with statistical tests, such as regression analysis, while someone with a quantitative background might lack the skills to conduct meaningful thematic coding or interpret narrative data. This lack of expertise can result in errors, such as misinterpreting statistical significance or failing to identify key themes in qualitative data. Addressing this challenge may require extensive training or collaboration with multidisciplinary teams, which can add to the complexity and cost of the research (Teddlie & Yu, 2007; Timans, Wouters, & Heilbron, 2019).

Philosophical and methodological tensions

Mixed methods research often confronts philosophical tensions between the paradigms underlying qualitative and quantitative methods. Qualitative research typically aligns with constructivist paradigms that focus on subjective interpretations and context-specific meanings, whereas quantitative research is grounded in post-positivist paradigms emphasizing objectivity and generalizability. For example, in a study on remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, surveys may reveal quantitative trends in students’ academic performance, while interviews might uncover emotional and social challenges not captured by those metrics. Reconciling these perspectives can be challenging, as qualitative findings might challenge the generalizations derived from quantitative data. Developing a unified theoretical framework that accommodates these differing epistemological assumptions requires intellectual rigor and careful justification, often becoming a contentious aspect of the research process (Mertens & Hesse-Biber, 2012; Migiro & Magangi, 2011).

Difficulty in data integration and interpretation

Integrating data from qualitative and quantitative sources is not merely a procedural step but a substantive intellectual task. In a study on healthcare access, surveys might measure patient satisfaction across various clinics, while interviews with patients and staff explore systemic barriers. To draw meaningful conclusions, researchers must synthesize the datasets, linking qualitative themes (e.g., long wait times) to quantitative measures (e.g., satisfaction scores). If qualitative and quantitative were collected from the same individuals, it is also important to systematically link all the data points belonging to the same person. It is important to plan for the need to link multiple datasets from the beginning so that consistent identifiers are used throughout the datasets. This process often involves converting themes into variables or developing overarching frameworks to explain the combined findings. Poor integration can result in superficial conclusions or a failure to address the research questions comprehensively. Advanced skills and tools, such as mixed methods matrices or software, are often required to handle this complexity effectively, but they may not always be available to researchers (Grech & Grech, 2021; Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018).

Merging data challenges

A fundamental aspect of mixed methods research is the integration of qualitative and quantitative findings, but this process can be fraught with difficulties. For example, a study on community resilience following a natural disaster might use surveys to quantify the levels of preparedness and qualitative interviews to understand residents’ lived experiences. However, integrating these datasets can become challenging if the findings are conflicting—such as survey results indicating high preparedness while interviews reveal feelings of anxiety and unpreparedness among participants. This discrepancy may arise due to differences in sampling methods, data quality, or measurement tools. Researchers must develop strategies such as triangulation, which involves cross-verifying data to ensure consistency and credibility. Without careful integration, the results risk appearing fragmented, and the overall conclusions of the study may lack coherence or robustness (Ozawa & Pongpirul, 2014; Grech & Grech, 2021).

Potential for methodological dominance

In mixed methods research, one methodological approach may overshadow the other, reducing the comprehensiveness of the findings. For instance, in a study on workplace diversity, the quantitative component (e.g., a survey on inclusion metrics) might dominate due to its ease of administration and analysis, while the qualitative component (e.g., in-depth interviews on employees’ experiences) receives less attention or resources. This imbalance can result in an incomplete understanding of the issue, as the qualitative data might reveal critical nuances, such as subtle biases or interpersonal dynamics, that surveys fail to capture. Ensuring equal representation of both methods requires careful planning and resource allocation, but researchers may struggle to maintain this balance, especially under time or funding constraints (Timans, Wouters, & Heilbron, 2019; Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018).

Generalizability issues

Mixed methods researchers might struggle to achieve balance between the generalizability of quantitative data and the depth of qualitative insights. For example, a study on teacher burnout might include a large-scale survey to assess burnout levels and qualitative interviews to explore coping strategies. While the survey data can generalize findings across a wide population, the interviews are limited to a small sample, making it difficult to extrapolate the nuanced themes to the broader population. Conversely, the richness of the qualitative findings may highlight key factors not captured by the quantitative data, creating tension in how the results are interpreted and applied. This trade-off can lead to challenges in meeting the expectations of stakeholders who value either the depth or breadth in the findings (Ozawa & Pongpirul, 2014; Vivek & Nanthagopan, 2021).

Conclusion

Mixed methods research offers a powerful way to explore complex issues by combining qualitative and quantitative data. However, it also presents significant challenges that require careful planning and expertise. The complexity of study design, the time and resources needed for data collection and analysis, and the difficulty of integrating two different types of data can make mixed methods research demanding. Researchers must navigate philosophical tensions between qualitative and quantitative paradigms while ensuring that one approach does not overshadow the other.

Despite these obstacles, mixed methods research remains valuable for generating rich, well-rounded insights. Thoughtful integration of data, collaboration with experts from both methodological backgrounds, and careful alignment of research objectives can help mitigate these challenges. By addressing these difficulties with a strategic approach, researchers can produce rigorous and meaningful findings that contribute to a deeper understanding of their research questions.

References

- Grech, P., & Grech, R. (2020). Stroke knowledge: Developing a framework for data integration in a sequential exploratory mixed method study. Research Methods in Medicine & Health Sciences, 2(2), 68–81.

- Migiro, S. O., & Magangi, B. A. (2011). Mixed methods: A review of literature and the future of the new research paradigm. African Journal of Business Management, 5(10), 3757–3764.

- Mertens, D. M., & Hesse-Biber, S. (2012). Triangulation and mixed methods research: Provocative positions. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 6(2), 75–79.

- Ozawa, S., & Pongpirul, K. (2014). 10 best resources on… mixed methods research in health systems. Health Policy and Planning, 29(3), 323–327.

- Teddlie, C., & Yu, F. (2007). Mixed methods sampling: A typology with examples. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(1), 77–100.

- Timans, R., Wouters, P., & Heilbron, J. (2019). Mixed methods research: What it is and what it could be. Theory and Society, 48(3), 193–216.

- Vivek, R., & Nanthagopan, Y. (2021). Review and comparison of multi-method and mixed method application in research studies. European Journal of Management Issues, 29(4), 200–208.