- What is Interview Analysis?

- Advantages of Interviews in Research

- Disadvantages of Interviews in Research

- Ethical Considerations in Interviews

- Preparing a Research Interview

- Recruitment & Sampling for Research Interviews

- Interview Design

- How to Formulate Interview Questions

- Rapport in Interviews

- Social Desirability Bias

- Interviewer Effect

- Types of Research Interviews

- Face-to-Face Interviews

- Focus Group Interviews

- Email Interviews

- Telephone Interviews

- Stimulated Recall Interviews

- Interviews vs. Surveys

- Interviews vs Questionnaires

- Interviews and Interrogations

- How to Transcribe Interviews?

- Verbatim Transcription

- Clean Interview Transcriptions

- Manual Interview Transcription

- Automated Interview Transcription

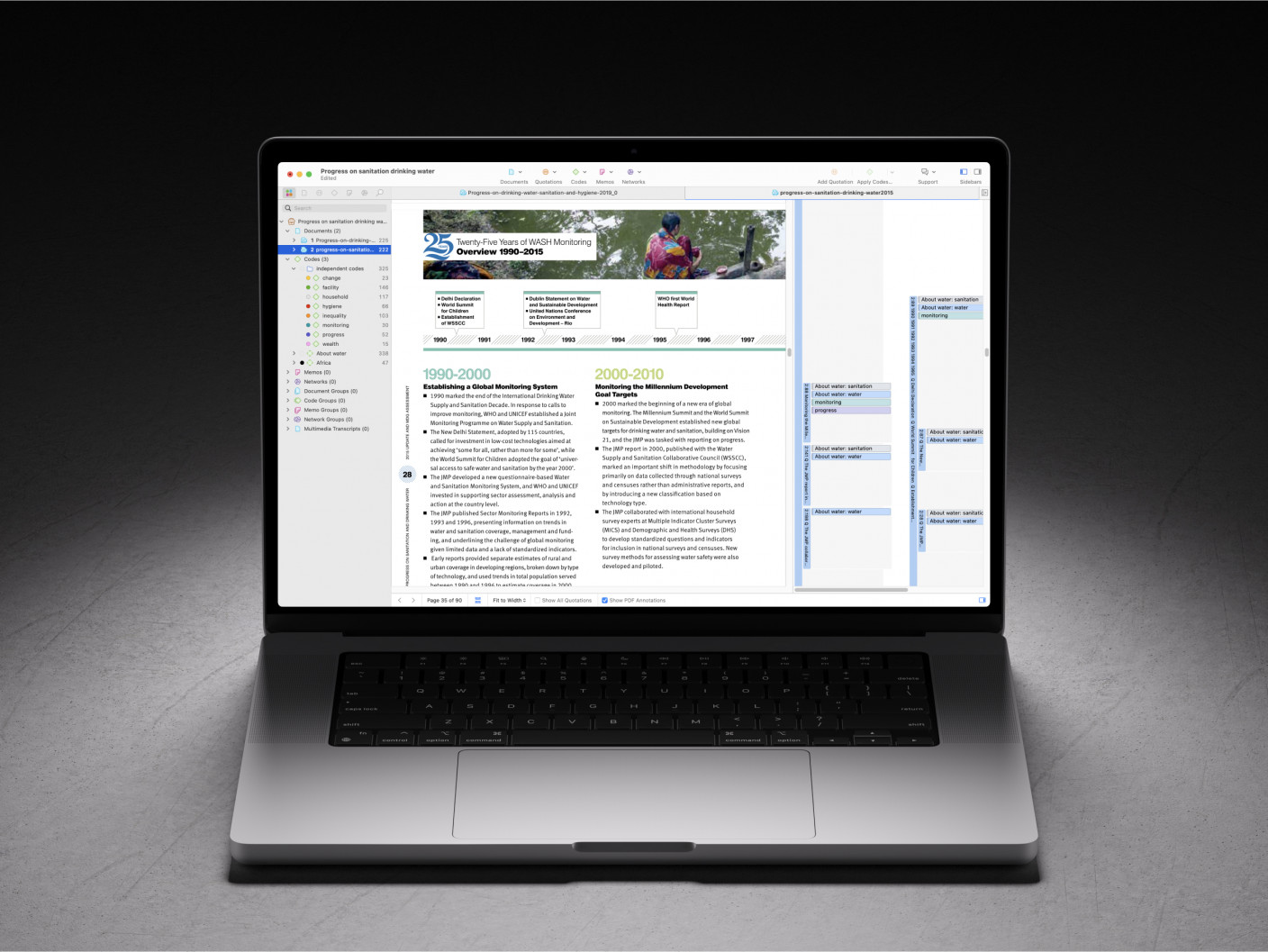

- Analyzing Interviews

- Coding Interviews

- Reporting & Presenting Interview Findings

Interview Design

In qualitative research, research design refers to the overall strategy and structure used to conduct a study. It outlines how data will be collected, analyzed, and interpreted to answer the research questions. Unlike quantitative research, which often follows rigid structures and focuses on numerical data, qualitative research designs are more flexible, allowing for deeper exploration of phenomena through non-numerical data such as interviews, observations, and texts. The following article will walk you through the key aspects of the research design process specific to interviews.

Introduction

In qualitative research interviews, the design is crucial for ensuring that the process captures meaningful and in-depth information. Whether you are conducting a structured interview with predetermined questions or an unstructured interview that unfolds like a normal conversation, the design shapes how effectively you gather insights that align with the research goals.

For many researchers, the process of designing an interview begins with establishing a solid foundation of questions—creating an interview guide that balances structure with flexibility. In a structured interview, questions are carefully crafted in advance, and the flow is consistent across interviews to allow comparability. However, when pursuing more nuanced data, open-ended questions are essential as they allow participants to express their experiences freely, often revealing layers of detailed information that structured questions might miss. This flexibility is especially evident in unstructured interviews, where the conversation evolves naturally, fostering a deeper connection and encouraging participants to explore topics that matter most to them.

The ability to pursue in-depth information in qualitative interviews depends not only on the questions asked but also on how the interviewer manages the conversation. For example, avoiding leading questions ensures that the participant’s responses are authentic and not influenced by the interviewer’s assumptions. Meanwhile, good note-taking during the interview helps capture key details without disrupting the flow of dialogue. Ensuring that you manage interview time efficiently is also crucial, as qualitative interviews often cover complex topics that require ample time for participants to reflect on their experiences.

One of the most important aspects of designing a qualitative interview is considering the participant's thought process. This means addressing terms and language used during the interview, making sure they are accessible and understandable to the participant. A well-designed interview should invite participants to think deeply about their responses, offering the space needed for reflection. While structured interviews provide consistency, more open formats allow for a richer exploration of the subject matter, capturing the full complexity of participants' experiences.

Ultimately, designing an interview in qualitative research is about balancing structure with adaptability. Whether it’s determining the best way to ask questions or managing practical aspects like note-taking and time management, interview design plays a pivotal role in obtaining in-depth information that enhances the quality of the research. The careful consideration of each element ensures that the interview process not only aligns with the research paradigm but also respects the participant’s experience, creating a path to insightful and meaningful data collection.

Interview design elements

When designing an interview, several key elements shape the entire process and are crucial for ensuring alignment with the research goals. Each aspect—from identifying the research paradigm, setting clear objectives to crafting thoughtful questions—plays a critical role in guiding how the interview is conducted, from beginning to end.

Research paradigm

The research paradigm is the philosophical lens through which the researcher views the world and the phenomena being studied. In qualitative research, the paradigm shapes how knowledge is understood and how the research is conducted. Common paradigms include:

Constructivism: This paradigm assumes that reality is socially constructed and subjective. Researchers working from a constructivist perspective aim to understand the multiple realities and perspectives of participants.

Interpretivism: In this paradigm, researchers seek to interpret and make sense of social realities based on participants' experiences and interactions. The focus is on understanding meaning, rather than measuring or predicting it.

Critical theory: This perspective focuses on power structures, inequality, and social change. Researchers in this paradigm aim to challenge and critique societal norms, often to promote transformation or empowerment.

The chosen paradigm directly influences the methods used in the study and the way data is interpreted.

Sampling strategy

Sampling in qualitative research is less about generalizing findings to a larger population and more about selecting participants who can provide meaningful, information-rich insights into the research topic. Key strategies include:

Purposive sampling: The researcher intentionally selects individuals who have experience or knowledge relevant to the research question. The goal is to gain detailed insight into specific contexts or experiences.

Theoretical sampling: Particularly used in grounded theory, this method involves selecting participants or data sources based on emerging theories. As new insights develop, the researcher identifies and recruits additional participants to refine or challenge the emerging theory.

Snowball sampling: This method involves asking existing participants to refer others who may have relevant experiences. It is particularly useful in hard-to-reach populations.

Convenience sampling: Convenience sampling involves selecting participants based on availability or ease of access. It may be useful in exploratory studies, but it is often considered less robust for drawing deep conclusions.

The sample size in qualitative research is usually smaller than in quantitative studies because the aim of data collection is depth, not breadth. The concept of data saturation—where no new information is obtained from additional participants and the explanation of the findings has been sufficiently developed—often determines when to stop sampling.

Additional data collection methods

While it is possible to collect all necessary data through interviews alone, researchers often find it beneficial to combine interviews with other data collection methods. This multimethod approach enriches the research by capturing different dimensions of the phenomenon under study. Common methods include:

Surveys: Incorporating surveys with open-ended questions can broaden the scope of data collection. While interviews typically involve a smaller number of participants due to their time-intensive nature, surveys can reach a larger audience, providing a wider range of perspectives. Open-ended responses in surveys can uncover prevalent themes or issues that warrant deeper exploration in interviews. Additionally, the anonymity of surveys might encourage participants to share more candid or sensitive information. It is common to collect anonymous survey data (e.g. in a company) and then interview a few people to gain a deeper understanding of the patterns found in the survey responses (this is common in mixed methods studies). Surveys can also be used to screen/select participants for an interview (e.g., if the respondent indicates they'd be willing to participate in an individual interview). it's common to collect anonymous survey data (e.g. in a company) and then interview a few people to gain a deeper understanding of the patterns found in the survey responses (this is common in mixed methods studies)

Observations: By systematically watching and recording behaviors and interactions in natural settings, researchers gain contextual information that might not emerge during interviews. Observations can reveal non-verbal cues, environmental factors, and actual behaviors, providing a valuable comparison to participants' reported experiences. This involves watching participants in their natural environment. Observations may be participant (where the researcher interacts with the participants) or non-participant (where the researcher remains detached). This method is useful for studying behaviors, processes, or interactions. Researchers usually conduct interviews with some of the people being observed such as in ethnographic studies.

Document or content analysis: Examining existing documents such as reports, emails, policy papers, or social media content offers historical context and background information relevant to the research topic. Document analysis can uncover patterns, themes, cultural norms, and procedural details that inform the phenomenon being studied. Analyzing secondary data (case studies) can be a powerful complement to conducting interviews.

Visual methods: The use of visual methods, such as photographs, videos, or drawings, can enhance the richness of qualitative data. Visual artifacts can capture aspects of experience that are difficult to articulate verbally. When participants create or interpret visual materials, they may express feelings or ideas that do not emerge in traditional interviews. Incorporating visual data can thus provide alternative insights and deepen the overall analysis.

Diaries or journals: Encouraging participants to maintain diaries or journals offers longitudinal data that captures changes over time. Personal writings provide intimate insights into participants' daily lives, thoughts, and emotions. Comparing diary entries with interview responses can reveal consistencies or discrepancies, contributing to a more layered understanding of the research subject.

Combining interviews with these complementary data collection methods enhances both the depth and breadth of the research. It allows for a more robust exploration of the research question by approaching it from multiple angles. This integration compensates for the limitations inherent in any single method and strengthens the study through methodological triangulation. By capturing a fuller picture of the phenomenon, researchers can produce findings that are both rich in detail and grounded in multiple forms of evidence.

Ethical Considerations

Ethics play a central role in qualitative research due to the often personal, sensitive, and close interaction with participants. The research design must ensure that ethical guidelines are strictly followed throughout the research process. Key considerations include:

Informed consent: Participants must be fully informed about the purpose of the research, how their data will be used, and any potential risks involved. Consent must be voluntary and can be withdrawn at any time.

Confidentiality: Participants’ identities must be protected, particularly when dealing with sensitive topics. This is often done by anonymizing data or using pseudonyms.

Non-maleficence: The research design should ensure that participants are not harmed emotionally, psychologically, or physically during the study. The researcher has a duty to protect participants from potential distress or exploitation.

Respect for autonomy: Participants should feel empowered and respected throughout the research process, including their right to decide what information they wish to share.

Flexibility

A key strength of qualitative research design is its flexibility. Unlike quantitative research, which typically follows a predetermined structure, qualitative research allows for adaptation as new insights emerge. This flexibility can manifest in:

Iterative data collection: Researchers often collect data in waves, analyzing initial findings and using them to guide further data collection. This iterative process allows researchers to refine their focus, explore new directions, and deepen their understanding of the research topic.

Evolving interview questions: Qualitative research designs are not rigid, so interview questions can evolve as the study progresses. If unexpected findings arise, the researcher may adjust their interview questions to explore these new insights.

Participant-driven data: In many qualitative designs, the participants’ experiences and perspectives shape the direction of the study. Researchers may adapt their questions or methods based on participant feedback and emerging themes.

Flexibility ensures that qualitative research remains responsive to the complexities of real-world phenomena, allowing for a more in-depth and nuanced exploration of the research question.

Interview questions and research questions

When designing a qualitative interview study, it's crucial to distinguish between the research question and the interview questions. The research question is the overarching inquiry that drives the entire study. It defines what the researcher aims to understand, explore, or uncover about a particular phenomenon. This question sets the direction for the research and influences every subsequent decision, from selecting participants to choosing data collection methods.

For example, a research question might be: "How do individuals experience the transition to remote work?"

This research question is not something you would directly ask your interviewees. Instead, it serves as a guiding framework for developing your interview questions.

The research question is essential because it:

- Provides focus: It narrows down the broad area of interest into a specific inquiry.

- Guides methodology: It influences the choice of research design, methods, and analysis.

- Motivates the study: It highlights the significance of the research and what it aims to contribute to existing knowledge.

Interview questions

Interview questions are the specific, open-ended questions you ask participants during the interview to gather data related to your research question. These questions are carefully crafted to elicit detailed, meaningful responses that provide insight into the participants' experiences, perceptions, or beliefs.

Continuing with the earlier example, interview questions might include:

- "Can you describe your daily routine since transitioning to remote work?"

- "What challenges have you faced while working from home?"

- "How has remote work impacted your work-life balance?"

Key characteristics of interview questions in qualitative research

Open-ended: Designed to encourage detailed responses, allowing participants to express themselves fully. Example: Instead of asking, "Do you like remote work?" you might ask, "What do you like or dislike about remote work?"

Exploratory: Aimed at uncovering deeper insights into behaviors, beliefs, and experiences. Example: "How has your perception of work changed since working remotely?"

Flexible and iterative: Can evolve during the research process as new themes or insights emerge. Example: If a participant mentions isolation as a significant issue, you might develop follow-up questions like, "Can you elaborate on how isolation has affected you professionally and personally?"

Starting the interview

Designing an interview involves deciding how you begin it, especially in qualitative research. Thoughtful planning sets the stage for a smooth, engaging conversation. When you design an interview, you're not just preparing questions—you're building a foundation that influences tone, rapport, and flow.

The purpose of your interview guides how you introduce it to participants. Clear introductions align with the goals you've set, helping participants feel comfortable from the start. The type of interview (structured, semi-structured, or unstructured) also dictates how you begin. Structured interviews may require a more formal approach, while unstructured ones allow for a relaxed, open-ended start.

Rapport-building is embedded in the design. A well-prepared opening creates a comfortable atmosphere, helping participants feel at ease. Setting expectations, such as the interview's length and purpose, ensures participants know what to expect, reducing uncertainty.

Opening questions designed during planning set the conversational flow, starting broad and easing into deeper topics. Thoughtful design also addresses participant anxiety by providing reassurance and fostering a sense of collaboration.

Time management is crucial—letting participants know the expected length and then sticking to it shows respect for their time. Finally, framing the research topic at the start, based on your design, helps participants understand the importance of their input.

In short, a well-designed interview creates the conditions for a smooth, insightful conversation, where preparation and flexibility meet to foster meaningful dialogue.

Conducting the interview

Conducting an interview stems directly from its design, ensuring the process flows smoothly while adapting in real-time. Flexibility is key; while the design sets a structure, being responsive to unexpected insights enriches the conversation. Well-crafted, open-ended questions invite reflection, and your role is to encourage deeper responses by using follow-ups or probes without leading the participant.

Maintaining rapport throughout the interview is essential. Engaging with verbal and nonverbal cues keeps the participant comfortable and willing to share more. At the same time, it’s important to guide the conversation without influencing their responses, ensuring neutrality while keeping the focus on the research goals.

Time management is critical. While the design outlines the pacing, you must ensure all topics are covered without rushing. Adapting to the participant’s needs, especially if sensitive topics arise, shows respect and creates a supportive environment.

Throughout the interview, stay neutral yet probe deeper into key themes. This ensures richer data without unduly shaping participants' responses.

In short, conducting an interview is about executing a thoughtful design while staying flexible and responsive to the participant’s experiences.

Ending the interview

Ending an interview thoughtfully is just as important as how you begin and conduct it, ensuring a smooth conclusion that leaves the participant feeling valued. While the design provides a framework, the final moments are where you bring everything together.

As you near the end, signal the interview’s conclusion by summarizing key points or thanking the participant for their time and insights. This reinforces the importance of their contribution and allows them to share any last thoughts or reflections. Avoid rushing through this moment, as it’s an opportunity to gather any additional insights.

Offer a brief overview of the next steps, such as how their responses will be used or when they can expect further contact, if relevant. This maintains transparency and keeps the participant informed about what to expect.

Ending with gratitude is key—acknowledging their time and effort helps leave a positive impression. By following the interview design but remaining attentive to the participant’s experience, the conclusion becomes a respectful and professional closure to the conversation.

The end of an interview ties everything together, leaving participants with a sense of purpose and appreciation for their involvement.

Conclusion

Designing an interview is about more than just asking questions—it’s about setting the stage for a meaningful conversation that brings out the depth and complexity of the participant’s experiences. A thoughtful design ensures that the process runs smoothly, keeping the conversation on track while allowing flexibility for unexpected insights. From selecting the right questions to maintaining rapport and managing time, every decision shapes the quality of the data collected.

When done well, interview design can foster open dialogue and uncover insights that might otherwise remain hidden. By striking a balance between structure and adaptability, researchers can create an environment that encourages genuine, thoughtful responses. This approach not only respects the participant’s input but also ensures that the research captures the full richness of the topic, leading to deeper, more impactful findings.