Objective vs Subjective Data | Key Differences

- Introduction

- What is objective data?

- What is subjective data?

- Examples of objective and subjective data

- Telling the difference between subjective and objective data

- What kind of qualitative data should I collect?

- What can I do with subjective data?

Introduction

Qualitative research is often associated with "subjective data", but what does that mean exactly? What makes data objective or subjective? And how do researchers account for subjectivities to generate empirical research?

In this article, we'll examine the distinction between subjective and objective data and how researchers employ both in their research to provide a rich perspective about the world.

What is objective data?

Objective data is any kind of data that is indexed to some objective measure. Most objective data is captured in numbers (e.g., temperature, age, population) but some numerical data may be subjective (e.g., movie review scores, perceived exertion during exercise) as they rely on some degree of human judgment.

Non-numerical data that is objective data includes things such as one's name, nationality, and place of birth. Ultimately, what makes objective data is that there is little contention about what the meaning of that data is. The population of a particular place is an absolute number and someone's place of birth is non-changeable once determined.

What is subjective data?

When researchers collect subjective information, they are collecting interpretations or knowledge that cannot be precisely measured by categories or numbers. What exactly makes one city more beautiful than another? How do you determine which roller coaster rides are the most exciting? What constitutes a healthy lifestyle?

In such cases, the meaning of this information can change depending on the person and cannot be objectively captured with a single, widely agreed upon measurement. Subjective data can come from many different qualitative research methods such as interviews and observations.

Examples of objective and subjective data

Let's imagine a study involving subjective and objective data in nursing and medical research. The kind of objective nursing data that you might collect from emergency rooms, hospital wards, and other medical care institutions includes vital signs like the patient's blood pressure, body temperature, or heart rate.

Likewise, subjective nursing data can take on various forms, such as personal feelings, opinions, even symptoms such as the level of pain or stress.

Subjective data can also include factors that are not strictly defined, such as the level of patient education about a particular treatment plan or a patient's experience with physical examinations. Oftentimes, subjective data from the medical fields comes from what a doctor, nurse, or patient tells in interviews or focus groups.

Telling the difference between subjective and objective data

Subjective and objective data often, but not always, fall along lines of qualitative and quantitative data. Knowing the difference may seem like a given, but it's important to detail the distinctions for the sake of rigorous research.

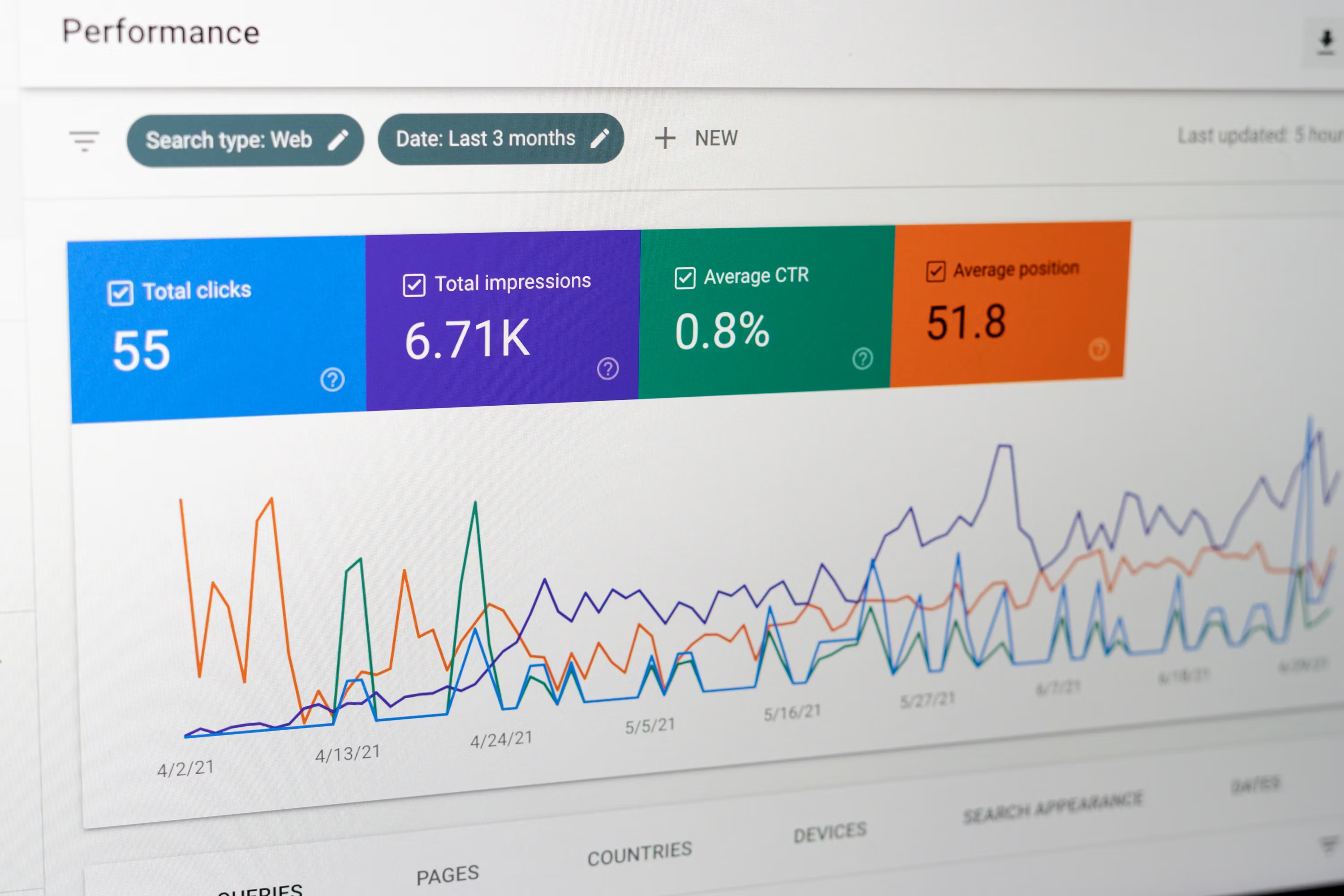

As mentioned above, objective data tends to be numerical in nature, which is often structured in tables, lists, and spreadsheets. Think about a weather forecast for cities around the world as an example, where each city is listed with high and low temperatures and chance of rain for the day.

Moreover, this example illustrates the unambiguous character of objective data. After all, "10 degrees Celsius" has a meaning in scientific and everyday contexts that cannot be subjectively construed or interpreted; while everybody reacts to cold weather in different ways, everyone agrees on the objective measure of the temperature.

In contrast, subjective data tends to take a more unstructured form. Sensations such as pain or anxiety are a matter of perception, which can only be described by those who experience these sensations. These interpretations are captured in interviews, focus group discussions, or observations, and are then transcribed or recorded in field notes to then be coded for analysis.

What kind of qualitative data should I collect?

The subjective vs. objective data argument is much like the qualitative vs. quantitative data debate: both divides are less about which one is better than the other and more about which is more appropriate for your research.

The "hard sciences" such as physics and chemistry primarily depend on objective data to explain the properties and behaviors of forces and objects in the natural world, while the social sciences or the "soft sciences" turn to subjective data to address research inquiries about social phenomena.

Ultimately, your research question will determine the object of your inquiry, which will in turn guide your study on what objective and subjective data to collect and analyze.

What can I do with subjective data?

It's important to emphasize that "subjective" doesn't mean "bad" or "flawed" data. On the contrary, subjective data often provides a rich depth of knowledge about the social world that absolute values cannot. It's simply a matter of interpreting it in a rigorous and reliable manner that yields valuable theoretical developments.

Qualitative researchers acknowledge that subjectivity is a necessary and useful element in understanding qualitative data that is either objective or subjective. The role of data analysis in handling subjective data is to contextualize it through triangulation and reflexivity.

Data triangulation, for example, is the concept of gathering information from multiple sources such as other patients or a family member related to a patient. The goal is not to get the same result from each source but to gather data about the same inquiry from multiple angles in the same context.

Mixed methods research naturally reiles on triangulation to confirm the analysis of one set of data with the analysis of another set. Mixed methods researchers often collect subjective and objective data within the same context to gather details from qualitative and quantitative methods.

For example, researchers might conduct an observation of communication between nurses about a patient diagnosis while also collecting data about vital signs and other assessments to conduct statistical analysis that contextualizes diagnostic practices in a hospital context.

Reflexivity is another essential researcher asset in contextualizing subjective data. Among other things, reflexivity involves the ability of the researcher to place themselves relative to the research context in which the data is collected. This requires acknowledging the differences in thinking between the researcher and their participants to place the data in its proper context.