La Guía del Análisis de Entrevistas

- ¿Qué es el Análisis de Entrevistas?

- Ventajas de Entrevistas de Investigación

- Desventajas de Entrevistas de Investigación

- Ética en las Entrevistas de Investigación

- Cómo Preparar una Entrevista de Investigación

- Reclutamiento y Muestreo para Entrevistas de Investigación

- Diseño de la Entrevista

- Cómo Formular Preguntas de Entrevista

- Rapport en las Entrevistas

- Sesgo de Deseabilidad Social

- Efecto del Entrevistador

- Tipos de Entrevistas de Investigación

- Entrevistas Cara a Cara

- Grupos Focales

- Entrevistas por Correo Electrónico

- Entrevistas Telefónicas

- ¿Qué es una entrevista de recuerdo estimulado?

- Entrevistas vs. Encuestas

- Entrevistas vs. Cuestionarios

- Entrevistas e Interrogatorios

- ¿Cómo transcribir entrevistas?

- Transcripción Literal

- Transcripción Limpia de Entrevistas

- Transcripción Manual de Entrevistas

- Transcripción Automática de Entrevistas

- ¿Cómo Anotar Entrevistas de Investigación?

- Formatear y Anonimizar Transcripciones de Entrevistas

- Análisis de Entrevistas

- Codificación de Entrevistas

- Presentación de los resultados de las entrevistas

- Cómo citar "La Guía del Análisis de Entrevistas"

Tipos de entrevistas de investigación

Aunque la realización de entrevistas en investigación comparte el mismo propósito de recopilar información en profundidad sobre un participante o un fenómeno, los distintos métodos permiten una recopilación más restringida o libre. Algunas entrevistas tienen preguntas específicas, mientras que otras son más flexibles y permiten improvisar preguntas. En este artículo, repasaremos los entresijos de los distintos tipos de entrevista para la investigación y explicaremos las diferencias entre los métodos estructurado, no estructurado y entrevista semiestructurada.

Introducción

La entrevista es un método habitual de recogida de datos en investigación cualitativa. La realización de entrevistas sirve de marco para registrar, cuestionar y reforzar prácticas y normas (Jamshed, 2014). La mayoría de las entrevistas se clasifican en una de estas tres categorías: la entrevista de investigación estructurada, semiestructurada o no estructurada. Estas entrevistas estructuradas y no estructuradas se diferencian por el grado en que se basan en preguntas predeterminadas, y cada enfoque viene con sus propias fortalezas y desventajas que consideramos con más detalle a continuación. Además, también analizamos otros métodos de investigación, como los grupos de discusión, para ofrecer otro punto de comparación con estos tres formatos principales de entrevista de investigación individual.

Una entrevista estructurada es ideal para recopilar datos coherentes y comparables, mientras que una entrevista no estructurada se asemeja a una conversación fluida entre el investigador y el participante en la entrevista. Entre estos dos extremos, las entrevistas semiestructuradas combinan tanto un conjunto de preguntas predeterminadas con espacio para la flexibilidad como preguntas espontáneas. Los grupos focales también permiten a los participantes expresarse abiertamente, pero la naturaleza grupal hace que las entrevistas a grupos focales sean más apropiadas para estudios que abordan la dinámica de grupo o la creación colectiva de significados. Dados los diversos puntos fuertes de cada método de investigación, se pueden encontrar en todos los ámbitos de investigación, desde etnógrafos que realizan entrevistas con métodos no estructurados en su trabajo de campo a largo plazo hasta investigadores sanitarios que realizan entrevistas con enfoques semiestructurados para sondear y explorar sistemáticamente un nuevo tema.

Entrevistas estructuradas

Las entrevistas estructuradas suelen utilizarse en la investigación cualitativa cuando el investigador busca una recogida de datos más controlada y sistemática. Estas entrevistas siguen un conjunto predeterminado de preguntas, manteniendo al entrevistador y al entrevistado centrados en temas específicos. Aunque las entrevistas estructuradas pueden carecer de la flexibilidad de los formatos no estructurados, tienen ventajas únicas que las hacen adecuadas para determinados contextos de investigación.

¿Cuándo son más útiles las entrevistas estructuradas?

Las entrevistas estructuradas funcionan mejor en investigaciones que se basan en un marco teórico bien definido. En estos casos, el entrevistador puede elaborar preguntas basadas en la investigación existente, lo que garantiza que los nuevos datos se basen en conocimientos previos. Este tipo de entrevista es especialmente útil cuando el investigador está seguro de qué preguntas son importantes y puede predecir con exactitud el tipo de información que necesita.

A diferencia de las entrevistas no estructuradas, que permiten respuestas más abiertas y preguntas de sondeo, las entrevistas estructuradas están diseñadas para recoger datos específicos. Este enfoque es ideal cuando el objetivo es obtener respuestas coherentes y comparables de múltiples participantes. Es menos adecuado para contextos de investigación exploratoria o cuando el investigador no está seguro de qué preguntas pueden aportar los datos más útiles.

Ventajas de las entrevistas estructuradas

Una ventaja clave de las entrevistas estructuradas es que permiten centrar la atención. Cuando la conversación sigue un conjunto estricto de preguntas, hay menos posibilidades de que la entrevista se desvíe del tema. Al ceñirse al guión, el entrevistador se asegura de que la conversación siga siendo pertinente y se ajuste a los objetivos de la investigación.

Las entrevistas estructuradas también facilitan la comparación de las respuestas de los distintos participantes. Como a todos se les hacen las mismas preguntas en el mismo orden, los datos recogidos son uniformes y más fáciles de analizar. Esta coherencia es una gran ventaja, sobre todo cuando se entrevista a grandes grupos de personas. Los investigadores pueden agrupar eficazmente las respuestas y buscar patrones o puntos en común.

Desde el punto de vista logístico, las entrevistas estructuradas suelen ser más fáciles de organizar. Dado que el entrevistador no tiene que improvisar ni formular nuevas preguntas, se requiere menos habilidad y experiencia para realizar una entrevista estructurada. Se puede formar fácilmente a los entrevistadores para que sigan una guía previamente escrita, lo que hace factible que los equipos de investigación deleguen esta tarea en asistentes.

Otra ventaja práctica es que las entrevistas estructuradas pueden realizarse con relativa rapidez. Dado que hay un conjunto fijo de preguntas, la duración de cada entrevista es predecible, lo que facilita la planificación de múltiples entrevistas en un periodo corto. Esta eficacia es valiosa cuando se trata de muestras de gran tamaño.

Desventajas de las entrevistas estructuradas

Las entrevistas estructuradas también tienen sus limitaciones. El inconveniente más notable es la falta de flexibilidad. Como las preguntas están predeterminadas, el entrevistador no puede hacer preguntas de sondeo ni profundizar en las respuestas del entrevistado. Esta rigidez puede impedir que el entrevistador comprenda plenamente el punto de vista del participante, sobre todo si un encuestado da una respuesta vaga o ambigua.

Además, las entrevistas estructuradas pueden no captar los matices o la complejidad de ciertas respuestas. Cada persona puede interpretar la misma pregunta de forma diferente, y la imposibilidad de ajustar las preguntas para aclararlas o profundizar en ellas puede dificultar la recopilación de datos. Por el contrario, las entrevistas no estructuradas permiten conversaciones más dinámicas, en las que el entrevistador puede adaptar las preguntas en función de las respuestas únicas del entrevistado.

El orden fijo de preguntas también puede ser problemático. Algunas preguntas pueden no resonar de la misma manera en todos los participantes. Por ejemplo, una pregunta que tiene sentido para un encuestado puede confundir a otro. En un formato no estructurado, el entrevistador tiene libertad para saltarse preguntas o reformularlas, pero las entrevistas estructuradas exigen que el entrevistador se ciña al guión.

En general, la mayor desventaja de las entrevistas estructuradas es el riesgo de limitar la investigación al conjunto inicial de preguntas. Por eso es fundamental que los investigadores elaboren cuidadosamente las preguntas de la entrevista y se aseguren de que abarcan todos los temas necesarios. Es muy recomendable realizar pruebas piloto de las preguntas para identificar cualquier problema o laguna antes de iniciar las entrevistas propiamente dichas.

Entrevistas estructuradas vs encuestas

Las entrevistas estructuradas suelen compararse con las encuestas con preguntas abiertas, ya que ambos métodos implican preguntas predeterminadas. Sin embargo, existen diferencias importantes. Mientras que las encuestas pueden llegar a un mayor número de encuestados, las entrevistas estructuradas ofrecen más oportunidades de aclaración. Si un encuestado tiene dificultades para entender una pregunta durante una entrevista, el entrevistador puede proporcionar contexto o ejemplos adicionales, lo que no es posible en una encuesta.

Otra ventaja de las entrevistas estructuradas es la interacción interpersonal entre el entrevistador y el encuestado. La comunicación cara a cara suele ayudar a construir rapport a que los encuestados se sientan más cómodos y dispuestos a compartir respuestas detalladas. Por el contrario, las encuestas, especialmente las escritas, pueden resultar impersonales y no suscitar la misma profundidad de respuesta.

Las entrevistas también suelen generar respuestas más ricas y detalladas que las encuestas. Cuando los participantes discuten temas de importancia personal, el formato de entrevista les da espacio para elaborar sus pensamientos, mientras que las encuestas pueden limitar sus respuestas.

Diseñar y realizar entrevistas estructuradas

A la hora de planificar una entrevista estructurada, el diseño de investigación desempeña un papel crucial. La guía de la entrevista, que contiene todas las preguntas que formulará el entrevistador, debe diseñarse cuidadosamente basándose en una revisión de literatura minuciosa. Así se garantiza que las preguntas sean pertinentes y se basen en la investigación existente.

Al diseñar la entrevista, es importante tener en cuenta las condiciones en las que se realizará. La uniformidad del entorno de la entrevista puede ayudar a mitigar los factores externos que pueden influir en las respuestas de los entrevistados. Por ejemplo, lo ideal es que las entrevistas se realicen en entornos tranquilos y cómodos para facilitar una comunicación abierta.

La creación de una guía de entrevista implica elaborar preguntas que se ajusten a los objetivos de la investigación y al marco teórico. El número de preguntas puede variar en función del tiempo disponible, pero es importante equilibrar la profundidad de las preguntas con la duración de la entrevista. La realización de entrevistas piloto ayuda a afinar las preguntas e identificar cualquier problema antes de que comience la recopilación de datos propiamente dicha.

Recopilación y análisis de datos

Recolección de datos en las entrevistas estructuradas es sencilla. El entrevistador graba las respuestas, normalmente utilizando una grabadora de audio o, en algunos casos, un equipo de vídeo para un análisis más profundo del lenguaje corporal y las expresiones faciales. Tras la entrevista, las grabaciones se transcriben para su análisis.

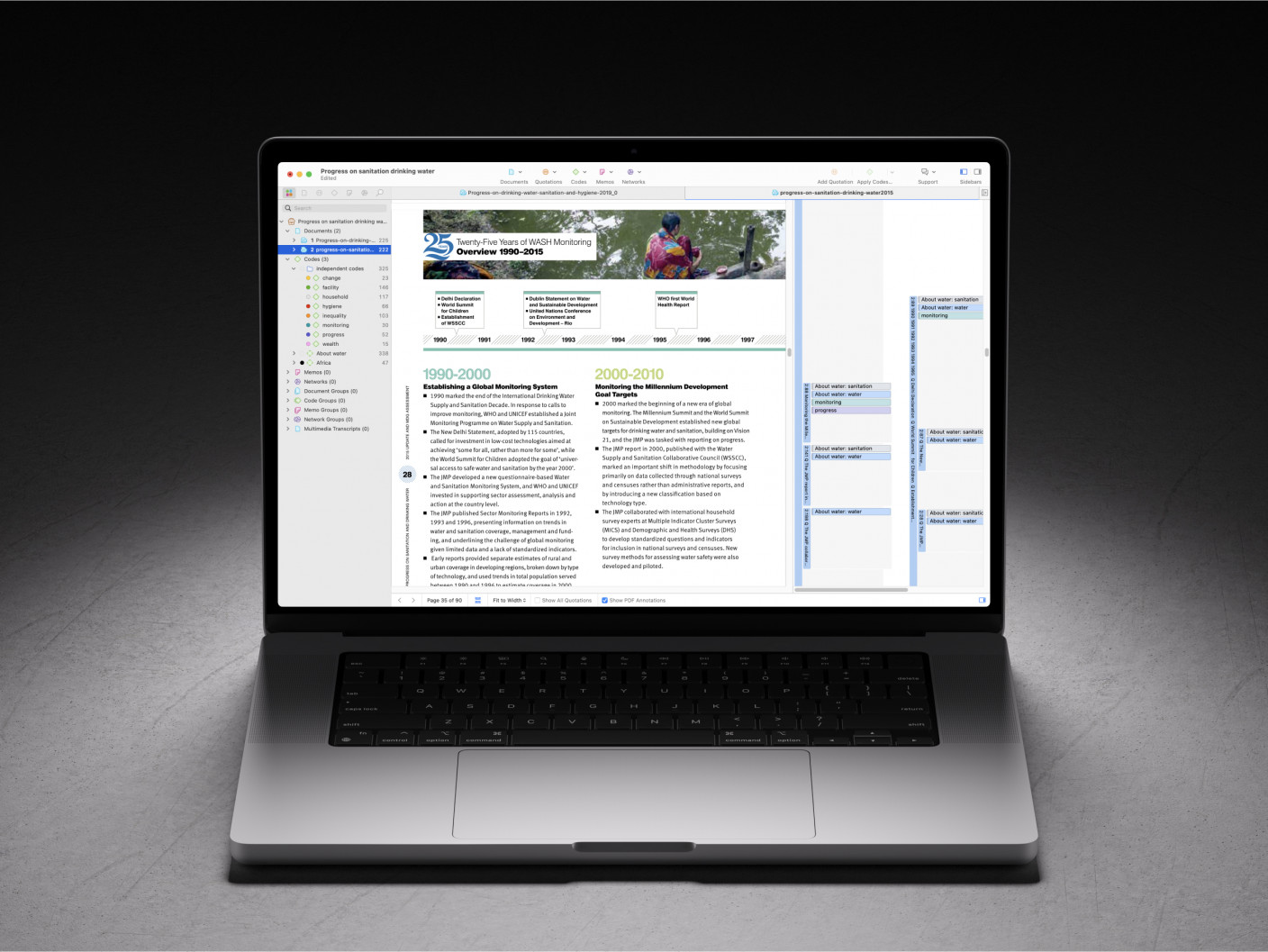

En la investigación cualitativa, análisis temático es un método habitual para analizar los datos de las entrevistas estructuradas. El investigador identifica los temas recurrentes y codifica las respuestas en consecuencia. Como las preguntas se formulan en un orden coherente, es fácil clasificar y comparar las respuestas de los distintos participantes. Herramientas informáticas como ATLAS.ti pueden ayudar a organizar y codificar los datos.

Entrevistas semiestructuradas

Las entrevistas semiestructuradas son un método eficaz de investigación cualitativa que permite una mayor flexibilidad que las entrevistas estructuradas, al tiempo que proporciona un marco para guiar la conversación. Este formato permite a los investigadores profundizar en las perspectivas de los entrevistados, ofreciéndoles la libertad de hacer preguntas de seguimiento, pero garantizando que se traten los temas esenciales.

Ventajas de las entrevistas semiestructuradas

La principal ventaja de las entrevistas semiestructuradas es la posibilidad de profundizar en las respuestas de los entrevistados. A diferencia de las entrevistas estructuradas, en las que las preguntas y el orden son fijos, las entrevistas semiestructuradas permiten al entrevistador hacer un seguimiento de puntos interesantes o inesperados. Esta flexibilidad ayuda a obtener información más rica y detallada que puede proporcionar una mayor comprensión del tema de investigación.

Otra ventaja es que, a pesar de la flexibilidad, las preguntas predeterminadas siguen proporcionando estructura. Esto garantiza que se exploren a fondo los temas clave relevantes para la investigación, incluso si la conversación toma diferentes direcciones. El equilibrio entre flexibilidad y estructura hace que las entrevistas semiestructuradas sean especialmente útiles en estudios en los que se necesita una combinación de profundidad y enfoque.

Desventajas de las entrevistas semiestructuradas

Sin embargo, la naturaleza abierta de las entrevistas semiestrucuturadas también puede ser una desventaja. Como a veces la conversación puede desviarse del tema, el entrevistador debe ser hábil para mantener la discusión en línea con la pregunta de investigación. Si la conversación se desvía demasiado, es posible que los datos recogidos no sean relevantes para los objetivos de la investigación, lo que dificultaría el análisis.

Otro inconveniente es que las entrevistas semiestructuradas requieren un entrevistador más comprometido. La escucha activa es fundamental para detectar oportunidades de preguntas adicionales, lo que significa que los entrevistadores necesitan formación suficiente. Los entrevistadores inexpertos pueden tener dificultades para mantener el equilibrio entre dejar fluir la conversación y mantenerla centrada en los objetivos de la investigación. Esto añade una capa de complejidad al proceso de entrevista que no está presente en formatos más estructurados.

Cuándo utilizar una entrevista semiestructurada

Las entrevistas semiestructuradas resultan más beneficiosas cuando un investigador pretende explorar experiencias y perspectivas individuales sobre un tema concreto. Este formato resulta especialmente útil para elaborar teorías en ámbitos en los que la bibliografía existente carece de coherencia teórica. Dado que la conversación puede adaptarse a las ideas del entrevistado, la entrevista semiestructurada permite a los investigadores profundizar en las ideas emergentes.

Los investigadores que utilicen las semi-entrevistas estructuradas deben tener una agenda clara y unos objetivos de investigación específicos para asegurarse de que las entrevistas se mantienen centradas. Estos objetivos guiarán las preguntas básicas planteadas a los entrevistados, al tiempo que permitirán flexibilidad para una exploración más profunda. En los estudios que pretenden explorar experiencias personales o elaborar teorías, el formato semiestructurado es ideal porque permite indagar en las ideas de los entrevistados sin perder de vista los objetivos de la investigación.

Mejores prácticas para realizar entrevistas semiestructuradas

Para llevar a cabo con éxito una entrevista semiestructurada se requiere una planificación cuidadosa e intencionada en cada etapa, desde la selección de los participantes hasta el diseño de las preguntas. Es fundamental elegir a participantes que se adapten bien al tema de la investigación. Por ejemplo, si la investigación se centra en una práctica cultural específica, los encuestados con experiencia directa o conocimiento de esa práctica proporcionarán los datos más relevantes.

También es importante prepararse a fondo para la interacción. Los investigadores deben evitar el uso de jerga o lenguaje demasiado complejo al formular las preguntas, y deben adaptar su lenguaje en función de los antecedentes del encuestado. Adaptar el enfoque en función de si los encuestados son adultos, niños o hablantes de distintas lenguas garantiza que la conversación siga siendo accesible y productiva.

Los investigadores también deben tener en cuenta el equipo utilizado para la recolección de datos. Aunque la grabadora de audio de un teléfono inteligente puede ser suficiente para captar la mayoría de las entrevistas, puede ser necesario un equipo profesional en entornos más ruidosos o cuando datos más matizados, como el lenguaje corporal o las expresiones faciales, son esenciales para el análisis.

Cuándo utilizar una entrevista semiestructurada

Las entrevistas semiestructuradas resultan más provechosas cuando un investigador pretende explorar experiencias y perspectivas individuales sobre un tema concreto. Este formato resulta especialmente útil para elaborar teorías en ámbitos en los que la bibliografía existente carece de coherencia teórica. Dado que la conversación puede adaptarse a las ideas del entrevistado, la entrevista semiestructurada permite a los investigadores profundizar en las ideas emergentes.

Los investigadores que utilizan entrevistas semiestructuradas deben tener una agenda clara y unos objetivos de investigación específicos para asegurarse de que las entrevistas se mantienen centradas. Estos objetivos guiarán las preguntas básicas planteadas a los entrevistados, al tiempo que permitirán flexibilidad para una exploración más profunda. En los estudios que pretenden explorar experiencias personales o elaborar teorías, el formato semiestructurado es ideal porque permite indagar en las ideas de los entrevistados sin perder de vista los objetivos de la investigación.

Mejores prácticas para realizar entrevistas semiestructuradas

Para llevar a cabo con éxito una entrevista semiestructurada se requiere una planificación cuidadosa e intencionada en cada etapa, desde la selección de los participantes hasta el diseño de las preguntas. Es fundamental elegir a participantes que se adapten bien al tema de la investigación. Por ejemplo, si la investigación se centra en una práctica cultural específica, los encuestados con experiencia directa o conocimiento de esa práctica proporcionarán los datos más relevantes.

También es importante prepararse a fondo para la interacción. Los investigadores deben evitar el uso de jerga o lenguaje demasiado complejo al formular las preguntas, y deben adaptar su lenguaje en función de los antecedentes del encuestado. Adaptar el enfoque en función de si los encuestados son adultos, niños o hablantes de distintas lenguas garantiza que la conversación siga siendo accesible y productiva.

Los investigadores también deben tener en cuenta el equipo utilizado para la recogida de datos. Mientras que la grabadora de audio de un teléfono inteligente puede ser suficiente para capturar la mayoría de las entrevistas, puede ser necesario un equipo profesional en entornos más ruidosos o cuando datos más matizados, como el lenguaje corporal o las expresiones faciales, son esenciales para el análisis.

Elaboración de preguntas de entrevista semiestructuradas

Preparar una guía para la entrevista es crucial cuando se realizan entrevistas semiestructuradas. Aunque la guía debe enumerar las preguntas clave y los temas a tratar, también debe ser lo suficientemente flexible como para permitir que la conversación fluya con naturalidad. Las preguntas deben ser abiertas para invitar a profundizar y evitar respuestas socialmente deseables.

Los investigadores también deben preparar de antemano preguntas de seguimiento o sondeos. Estas preguntas pueden animar a los encuestados a ampliar sus respuestas o aclarar puntos que parezcan poco claros. Las preguntas de sondeo ayudan a superar el reto de las respuestas breves o poco comprometidas, invitando a los participantes a ampliar sus ideas.

Recopilación y análisis de datos de entrevistas semiestructuradas

Durante y después de la entrevista, los investigadores deben asegurarse de recopilar los datos cualitativos de forma rigurosa. Lo más habitual es transcribir grabaciones de audio o vídeo de las conversaciones de la entrevista. Las grabaciones de alta calidad son esenciales para una transcripción precisa, y a menudo es beneficioso utilizar software de transcripción o servicios profesionales para agilizar el proceso.

Una vez transcritos los datos, pueden analizarse utilizando un software de análisis de datos cualitativos como ATLAS.ti. El software ayuda a organizar y analizar los datos. La codificación suele comenzar con la organización de las respuestas según las preguntas de la guía de la entrevista, lo que permite al investigador comparar las respuestas de todos los participantes. Una codificación adicional basada en temas emergentes puede proporcionar una visión más profunda de los datos.

Además de la codificación, los investigadores deben considerar la posibilidad de tomar notas durante y después de la entrevista. Estas notas pueden captar observaciones importantes sobre la interacción, que pueden no ser evidentes en la transcripción por sí sola. Por ejemplo, las señales no verbales, como el lenguaje corporal o el tono de voz, pueden añadir un contexto valioso a las respuestas verbales.

Preparación de las entrevistas semiestructuradas para el análisis

Una vez finalizada la entrevista, el proceso de investigación no se detiene en la transcripción. Los investigadores deben analizar cuidadosamente los datos recopilados para identificar temas y patrones relevantes para sus preguntas de investigación. La precisión de la transcripción es vital para un análisis exhaustivo, y los investigadores pueden querer incluir detalles como pausas o sonidos de pensamiento si son relevantes para el estudio.

Tras la transcripción, la codificación ayuda a organizar los datos en categorías significativas. Este proceso ayuda a los investigadores a explorar patrones en las experiencias y perspectivas de los participantes, lo que permite una comprensión más profunda del tema de investigación.

Entrevistas no estructuradas

Las entrevistas no estructuradas, a menudo denominadas entrevistas no directivas, son muy conversacionales y flexibles. En este método, el entrevistador puede empezar con un tema general, pero deja que la conversación fluya con naturalidad, animando a los participantes a compartir libremente sus pensamientos y experiencias. Las entrevistas no estructuradas son especialmente eficaces para explorar temas de investigación nuevos o complejos en los que el investigador busca descubrir puntos de vista inesperados. La naturaleza abierta de estas entrevistas puede producir datos ricos y detallados, pero la falta de estructura puede dificultar la comparación de las respuestas entre los participantes y hacer que el proceso de recogida de datos lleve más tiempo.

Cuándo utilizar entrevistas no estructuradas

Las entrevistas no estructuradas son especialmente adecuadas para la investigación exploratoria los casos en que el objetivo es desarrollar una comprensión profunda de un fenómeno, sobre todo cuando hay poca teoría existente para guiar la investigación. Este enfoque se utiliza a menudo en estudios cuyo objetivo es recopilar "descripciones densas", término que hace referencia a la exploración detallada de las perspectivas de un encuestado para comprender la complejidad de los fenómenos sociales.

Por ejemplo, en estudios que examinan temas delicados como los cuidados paliativos o el trabajo de los inmigrantes, los encuestados pueden mostrarse más reacios a abrirse si se les plantean preguntas directas o estructuradas. Las entrevistas no estructuradas permiten a los investigadores establecer una buena relación con los participantes, creando un entorno más cómodo para que compartan abiertamente sus pensamientos y experiencias.

Cuando el objetivo principal es desarrollar la confianza y la compenetración, las entrevistas no estructuradas ofrecen una forma eficaz de implicar a los participantes. La falta de una estructura rígida permite que la conversación fluya de forma más natural, lo que puede hacer que los entrevistados se sientan más a gusto, aumentando así la probabilidad de recopilar datos significativos.

Ventajas de las entrevistas no estructuradas

Una de las principales ventajas de las entrevistas no estructuradas es su naturaleza abierta, que permite que la conversación avance en cualquier dirección que pueda surgir de forma natural. Aunque el entrevistador suele tener un objetivo de investigación claro, la falta de una estructura rígida da a los entrevistados un mayor control sobre la interacción. Esto puede animarles a dar respuestas más detalladas y profundas, sobre todo al tratar temas delicados o experiencias personales.

La libertad de explorar las perspectivas de los entrevistados en mayor profundidad hace que las entrevistas no estructuradas sean ideales para los estudios que pretenden recopilar datos cualitativos ricos. Los investigadores pueden obtener una comprensión más matizada de los puntos de vista, las costumbres sociales o las prácticas culturales de los entrevistados, especialmente en ámbitos en los que los conocimientos existentes son limitados.

Desventajas de las entrevistas no estructuradas

A pesar de sus ventajas, las entrevistas no estructuradas presentan varios inconvenientes. Uno de los principales inconvenientes es la dificultad para analizar y comparar los datos recogidos de distintos participantes. Dado que cada entrevistado puede centrarse en aspectos diferentes del tema, los datos pueden ser diversos y menos coherentes, lo que dificulta la integración de las distintas perspectivas en un análisis coherente.

Otro posible inconveniente es el riesgo de que la conversación se desvíe demasiado del tema de la investigación. Dado que no hay un conjunto predeterminado de preguntas, el entrevistador debe gestionar cuidadosamente el flujo de la conversación para asegurarse de que se está recopilando información valiosa. Si el entrevistador pierde la concentración, la entrevista puede salirse por la tangente y obtener datos irrelevantes.

Proceso de la entrevista no estructurada

Aunque las entrevistas no estructuradas no siguen una lista fija de preguntas, requieren una planificación cuidadosa. El entrevistador debe tener una idea clara del tema de la investigación y de los objetivos que pretende alcanzar. Aunque puede que no haya preguntas específicas para guiar la entrevista, el entrevistador debe tener una serie de temas clave que quiere explorar durante la conversación.

Otro aspecto crucial de las entrevistas no estructuradas es la capacidad del entrevistador para adaptarse a la conversación en tiempo real. Esto significa saber cuándo hacer más preguntas de sondeo y cuándo dejar que el entrevistado dirija la conversación. La capacidad de leer las señales sociales y ajustar las preguntas en función del nivel de comodidad del entrevistado es esencial para recopilar datos con éxito en este formato.

La fase de recolección de datos en las entrevistas no estructuradas puede ser uno de los aspectos más dinámicos del proceso de investigación. Dado que no existe un guión predeterminado, el entrevistador debe guiar la conversación con cuidado, animando al entrevistado a compartir relatos detallados. Es esencial establecer una buena relación, ya que fomenta un entorno en el que los entrevistados se sienten cómodos hablando abiertamente de sus pensamientos.

El entrevistador debe tratar de obtener relatos detallados de los encuestados, evitando al mismo tiempo preguntas capciosas que puedan influir en sus respuestas. Empezar con preguntas sencillas y no amenazadoras es una buena forma de establecer una buena relación antes de pasar a temas más complejos o delicados.

Cómo analizar entrevistas no estructuradas

El análisis de los datos de las entrevistas no estructuradas requiere un enfoque sistemático para dar sentido a las respuestas, a menudo variadas. Normalmente, los datos de la entrevista se transcriben, lo que permite al investigador buscar frases, patrones o ideas importantes. Un programa de análisis de datos cualitativos como ATLAS.ti puede ayudar a organizar y codificar los datos. Este programa ayuda a los investigadores a identificar los temas clave y a comparar las respuestas de los distintos participantes.

La codificación es una parte esencial del proceso de análisis. Los investigadores pueden empezar creando una lista de códigos preliminares basados en sus preguntas de investigación, pero deben permanecer abiertos a nuevos códigos a medida que analizan los datos. Por ejemplo, pueden realizar un análisis temático, que consiste en identificar temas recurrentes o experiencias compartidas entre los encuestados.

Las entrevistas no estructuradas también pueden analizarse utilizando la codificación discursiva, que se centra en cómo hablan los entrevistados sobre un fenómeno concreto. Este enfoque es útil cuando el objetivo es explorar cómo los individuos construyen significados en torno al tema de interés.

Grupos de enfoque

Un grupo de enfoque en investigación es un método cualitativo que implica a un pequeño grupo de personas que participan en un debate guiado por un moderador. Los grupos focales son interactivos y permiten a los participantes compartir sus opiniones y perspectivas sobre un tema, producto o servicio. Este método se utiliza habitualmente en los estudios de mercado y las ciencias sociales para observar el comportamiento social y la dinámica de grupo de un modo que las entrevistas individuales o las observaciones no permiten.

Propósito de un grupo de enfoque

El objetivo principal de un grupo de enfoque es recopilar diversos puntos de vista y opiniones que surgen en un entorno de grupo. Los grupos focales resultan especialmente útiles en situaciones en las que los investigadores necesitan comprender cómo interactúan las personas entre sí al debatir un tema. Pueden utilizarse para explorar nuevas ideas, poner a prueba conceptos u obtener información sobre comportamientos sociales. La interacción dinámica entre los participantes permite a los investigadores observar cómo se forman y evolucionan las opiniones en un entorno social.

Tamaño y composición

Un grupo focal típico consta de 6 a 10 participantes, moderados por un facilitador. Este tamaño permite una variedad de perspectivas y garantiza que todos tengan la oportunidad de contribuir. Contar con muy pocos participantes puede limitar la diversidad de opiniones, mientras que demasiados puede dificultar la gestión del debate y garantizar que se escuchen todas las voces.

Cómo funcionan los grupos focales

Los grupos focales suelen incluir una serie de preguntas abiertas preparadas de antemano por el investigador. Estas preguntas sirven para suscitar el debate y guiar a los participantes para que compartan sus ideas sobre el tema en cuestión. Las preguntas son amplias y no directivas, y animan a los participantes a expresarse libremente con sus propias palabras. El papel del moderador es mantener el hilo de la conversación, pedir más detalles cuando sea necesario y asegurarse de que todos los participantes tengan la oportunidad de contribuir.

Eficacia de los grupos focales

Lo que hace que los grupos focales sean especialmente eficaces es la interacción social entre los participantes. A diferencia de las entrevistas individuales, los grupos de discusión permiten a los investigadores observar cómo influye en las opiniones la dinámica de grupo. La naturaleza de ida y vuelta del debate puede estimular nuevas ideas, revelar áreas de acuerdo o desacuerdo y poner de relieve cómo las personas negocian y crean consenso. Estas interacciones proporcionan una visión más profunda no sólo de lo que piensa la gente, sino también de cómo y por qué mantienen determinadas opiniones.

Los grupos focales son versátiles y pueden utilizarse en una amplia gama de contextos de investigación. Son especialmente valiosos en la investigación exploratoria, en la que el objetivo es obtener una comprensión preliminar de una cuestión nueva o compleja. La naturaleza interactiva de los grupos de discusión ayuda a los investigadores a identificar temas clave, generar propuestas de investigación y profundizar en su comprensión del tema de investigación. Este enfoque también es útil para generar nuevas ideas en campos como el desarrollo de productos, la elaboración de políticas y el diseño de programas.

Además de generar ideas, los grupos de discusión ayudan a los investigadores a comprender el lenguaje y la terminología que utilizan los participantes al hablar de un tema. Este conocimiento puede ser crucial para elaborar encuestas, interpretar datos cualitativos o entender cómo la gente da sentido a sus experiencias.

Conclusión

Los distintos tipos de entrevistas ofrecen ventajas y desafíos diferentes, cada uno de ellos adecuado para objetivos y contextos de investigación particulares. Las entrevistas estructuradas ofrecen coherencia y facilidad de comparación, por lo que son ideales para estudios que requieren una recogida de datos estandarizada. Las entrevistas semiestructuradas logran un equilibrio entre flexibilidad y estructura, lo que permite a los investigadores explorar temas clave a la vez que profundizan en las perspectivas de los entrevistados. Las entrevistas no estructuradas ofrecen la mayor flexibilidad, permitiendo a los investigadores recopilar datos ricos y en profundidad en un formato abierto y conversacional, especialmente útil en la investigación exploratoria. La elección del tipo de entrevista adecuado depende de los objetivos de la investigación, la naturaleza del tema y la profundidad deseada en la recopilación de datos, lo que garantiza que el método elegido se ajuste a las necesidades del estudio para recopilar información valiosa.

Referencias

- Jamshed S. (2014). Método de investigación cualitativa-entrevista y observación. Journal of basic and clinical pharmacy, 5(4), 87-88. https://doi.org/10.4103/0976-0105.141942